Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg from the Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich: so dark and disturbing that it makes uncomfortable viewing. But truly great works of art operate on many levels, the greater the piece the greater the possibilities. It is a measure of Wagner's greatness that the ideas he dealt with nearly 150 years ago apply, almost frighteningly, to the present. This Meistersinger provokes more questions than it gives answers, exactly what we need at the present when assumptions about art, politics and society are in unprecedented flux.

Who are the Meistersingers? Wagner makes a point of describing them as distinct individuals, with different backgrounds, united more or less by their love for art. All of them have other day jobs: art is something they choose to place their faith in. Although Hans Sachs and Sixtus Beckmesser dominate, it is wise to consider the Meistersingers as a group of personalities resolving the inevitable conflicts of diversity through compromise. Rules help them muddle through by providing a kind of framework in which to regulate their art. But the rules are, in fact, made up ad hoc. Beckmesser is so obessesed with finding fault that he runs out of space on his marking slate. He works himself into crazed frenzy. Reality is never quite so extreme. Yet the Meistersingers, supposedly wise representatives of common sense, get caught up in Beckmesser's hysteria and hate. How easily civilized society can disintegrate when demagogues take control! Were it not for Hans Sachs and the voice of reason, Walter von Stoltzing, and what he stands for, would have been driven out of Nuremberg forthwith. How easily society descends into mindless, repression and group think. What kind of society cannot cope with change and must suppress new ideas?

The Meistersingers here are depicted as ordinary men, to whose credit have worked hard to make something of their craft. Ordinary men, who've meant well. They think they're in control, but are easily manipulated into forgetting the very fundamentals of art, that art should enhance life, and must, like Nature itself, constantly refresh. Hence the urban landscape. Walter learned his art from the birds in the woodland, who are free. Birds don't survive in these grim conditions. As Wagner clearly stated in his stage directions, angles in the Church are distorted. Something's askew. Eva (Emma Bell) participates in formulaic rituals but recognizes Walter (Robert Künzli) as a fellow free spirit right from the start. The apprentices, being young, are also still untamed, but how is their energy directed. Just as each of the Meistersingers is defined as a distinctive personality, this David (Benjamin Bruns) isn't a stereotype but a well-characterized combination of worthiness and weakness, not a youth but not yet an artist until the end.

In the First Act, the staging sets the personalities. In the Second, the staging focuses on the community. Sachs (Wolfgang Koch) operates out of a van marked "Schuhe". It reminds us that Sachs is out in the open, in the night air. Is he a Wanderer, who sees all yet can't easily intervene? There's no tree in this square, but a cherry picker crane that can be cranked up and down if needed, a stage idea that's more effective than it looks. Beckmesser can reach great heights, but by artificial means, reflecting the idea of an elder tree and its connotations of delusion.

Similarly, this Beckmesser (Martin Gantner) isn't a caricature, but is interpreted as a weak but opportunistic personality who assumes that playing the right games gets you ahead. He's very nearly right. Were it not for Sachs, his gold lamé suit and string vest might make him a superstar in some eyes, though his instrument is minute. Walter, in leathers, looks like a thug but is the true artist, rough edges and all. David could go either way, meaning well but prone to fudging corners. Wolfgang Koch's Sachs impressed: although he's grimy (as the real Sachs probably was), intelligence shines out of his eyes. His movements are sharp and he takes in all that's happening around him, as a good Sachs should. Koch is so experienced that authoritative singing comes naturally to him: no need for exaggerated folksiness. His "Wahn! Wahn! Überall Wahn!" sounded genuinely perplexed, as if he were trying to make sense of what's going wrong, rather than just sighing in despair. As he sang, his voice warmed with resolve. Sachs can, and will, stand up for reason.

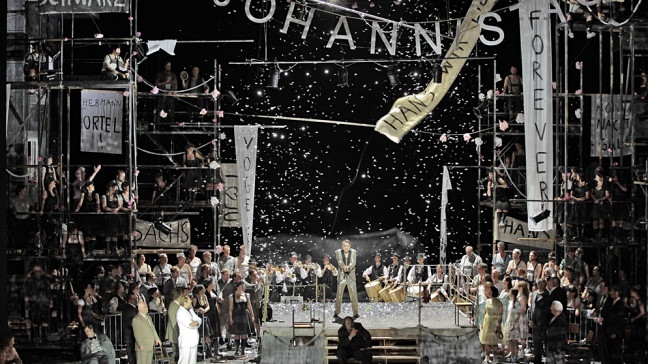

No open meadows in the final scene. Perhaps the Pegnitz no longer flows, or has been diverted underground. We still see flags but these are flags of a more sinister kind. We're indoors, in a closed auditorium, cut off from the real world. On a hot Johannisnacht, the atmosphere would be stifling. And so, perhaps, a commentary on the nature of guilds and competition, of the channeling of diversity into an apparently cohesive celebration. "Brought to you by Pogner", a sign declares, for Pogner (Georg Zeppenfeld) was the agent who created the situation through which Eva was auctioned off to the highest bidder, bringing out the worst in Beckmesser, who might not otherwise have dared to move. Pogner's white suit isn't as pure as it might seem. The mob in the square covered the city walls in graffiti. Here, the "promoters" cover the meadow with commercial slogans. Either way, defacement, and the defacement of culture as sacred mission.

The guilds come together in a show of unity, but how much of this unity is real, and how much controlled by convention. Each guild flaunts its superiority. Listen to the music: "Streck'! Streck'! Streck'!" and "Beck! Beck! Beck!", violence channelled into ostensibly cheerful chorus. The Tailors hold up the tools of their trade: giant scissors which could cut a man in two, stained with blood. In some shots the blades of the scissors appear above the tailor's heads as if they were the horns of the devil. The Prize scene is a Prize Fight, but the wider scene suggests a kind of Party Rally, with the crowds cheering as if on cue. Alas, Nuremberg has yet to live down 1936, even though not all the good folk of the city were participants. But at least the memory serves to remind us how dangerous Party Rallies can be, when people can be manipulated into unthinking frenzy and violence. Even decent, ordinary people who let themselves be fooled by soundbites. No wonder Walter doesn't want more of the same. Beckmesser gets beaten yet again, and brutally, this time shooting himself. Fortunately, though, Walter does win, and wins Eva, the two of them offering hope by renewal. What Walter will learn from Sachs will determine the direction of Holy German Art.

How much have audiences learned from Wagner, and from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, though, I wonder ? In the dark clouds gathering around us in 2016, have we learned anything from history? Can art save civilization? Or is human nature so venal that the ideals of enlightenment must be destroyed in a wave of ever-narrowing bigotry and the resurgence of fascist values? In this production, the bust of Wagner comes in a box marked "fragile". Fortunately in Munich, the cheers were louder than the boos, a cause for hope. Kirill Petrenko conducted a very good cast even without a megastar like Jonas Kaufmann. For that, I was glad, for Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. This production, directed by David Bösch, is finely detailed and will probably reveal its depths as time goes on. It's different, but its insights come from the opera itself. It's not easy. But the issues it confronts are not easy and need to be confronted with courage and with Hans Sachs's fair minded common sense.

How much have audiences learned from Wagner, and from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, though, I wonder ? In the dark clouds gathering around us in 2016, have we learned anything from history? Can art save civilization? Or is human nature so venal that the ideals of enlightenment must be destroyed in a wave of ever-narrowing bigotry and the resurgence of fascist values? In this production, the bust of Wagner comes in a box marked "fragile". Fortunately in Munich, the cheers were louder than the boos, a cause for hope. Kirill Petrenko conducted a very good cast even without a megastar like Jonas Kaufmann. For that, I was glad, for Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. This production, directed by David Bösch, is finely detailed and will probably reveal its depths as time goes on. It's different, but its insights come from the opera itself. It's not easy. But the issues it confronts are not easy and need to be confronted with courage and with Hans Sachs's fair minded common sense.

No comments:

Post a Comment