"Tradition ist nicht die Anbetung der Asche, sondern die Bewahrung und das Weiterreichen des Feuers" - Gustav Mahler

Saturday, 31 March 2018

Wednesday, 28 March 2018

Patron Saint of Voice Science

Nearly 40 years ago, in a junk shop in what was then a remote village in South Buckinghamshire, I found a musty old treatise on treating canine distemper with herbal techniques. The author was a scientist, in the Victorian manner when anyone could set up experiments on their own and develop theories. The author was originally German, with some training in medicine, which is why he used the title "Doctor Professor". Arriving in Britain at some time in the 1870's or 80's, he settled in a village near where I found the book, running a laboratory of some sort, closely guarded first by his English wife and then by his daughter, who stayed in the house as a recluse into the late 1930's. Dog medicine was just of one his interests.

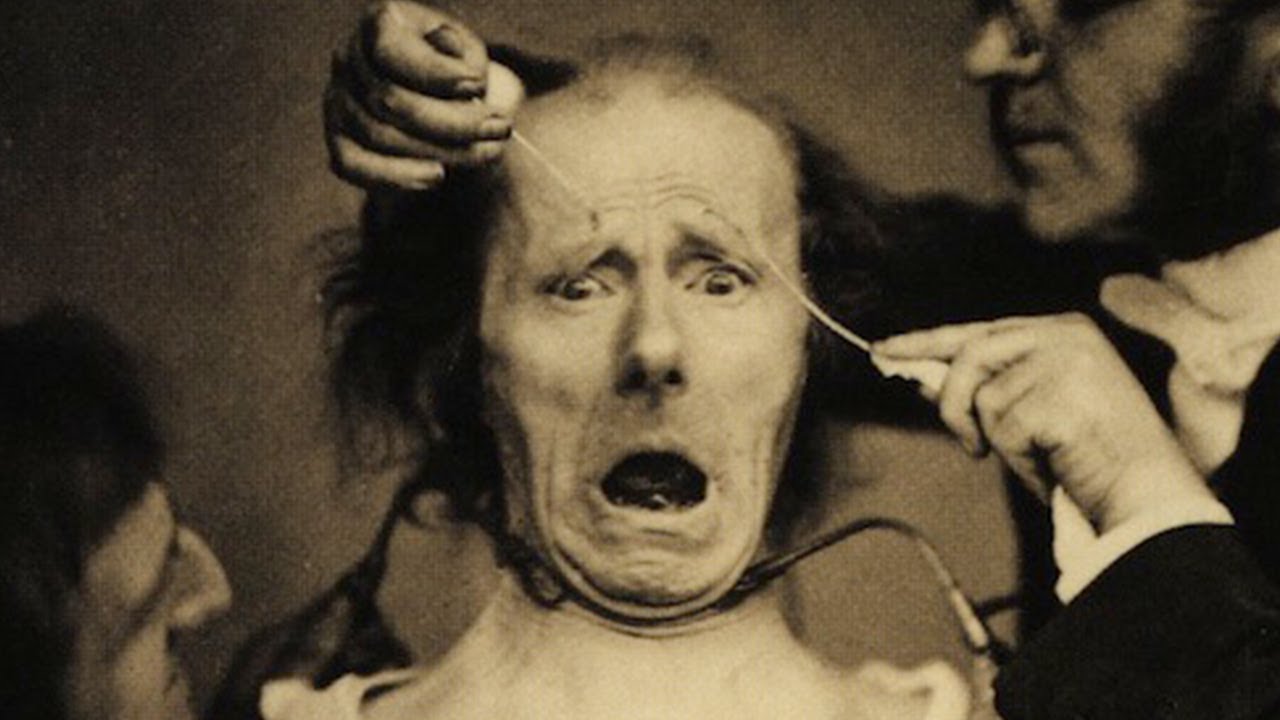

The good doctor's main thing was Voice Science, and the techniques of singing. With his training in anatomy, he constructed an intricate contraption with cadaver parts. Real lungs, real vocal cords, muscles, mouth, lips and tongue, preserved in some kind of formaldehyde which retained flexibility. Bellows were used to blow air into the lungs, from the nose down and then out again. Wires and levers connected the body parts so they moved when electrical stimuli were applied. The contraption was so accurate that it did "sing", emitting sounds in different ways depending on how much pressure was used on what part of the mechanism, and how much air was being pumped through. The doctor documented the various methods by which he could replicate the mechanics of voice production. Head voice! Chest voice ! Corpse tongue and mouth muscles ! Was the doctor a pioneering patron saint of bad singing ? Things like artistry, sensitivity and even repertoire can't so easily be regulated.

Tuesday, 27 March 2018

BBC Proms website malfunction

A few weeks to go before the Proms are announced, but high time someone should look at the website. There's a bug in the system, blocking access to the Proms Performance Archive for Composers. It keeps defaulting to 2017. (There is a devious way - if you get to "performers" try clicking on "Composers" and wait. Evntuallyit does sometimes go there, but inconvenient). Please fix ! The philosophy these days seems to favour performance measures by the Proms management, over and above performance as musical experience. Thus the obsession with first time visitors, and visitors who wouldn't normally go to classical music. That's a political agenda, not an artistic agenda. The BBC's own research shows that first timers don't always get hooked as often as presumed, even if they're polite and say they might. People come to classical music when they're ready, and by many different routes, so the whole philosophy of First Timers Above All Else is fundamentally flawed. It's sloppy to place all hopes on one doubtful strategy, while sacrificing the core audience, and the Product itself . It might take ages for common sense to trickle down. Yes, it's nice to know the (non-existent) dress code, but for many of us, especially regulars, it's important to access the archive.

Monday, 26 March 2018

Debussy and Beyond - François-Xavier Roth, LSO Barbican

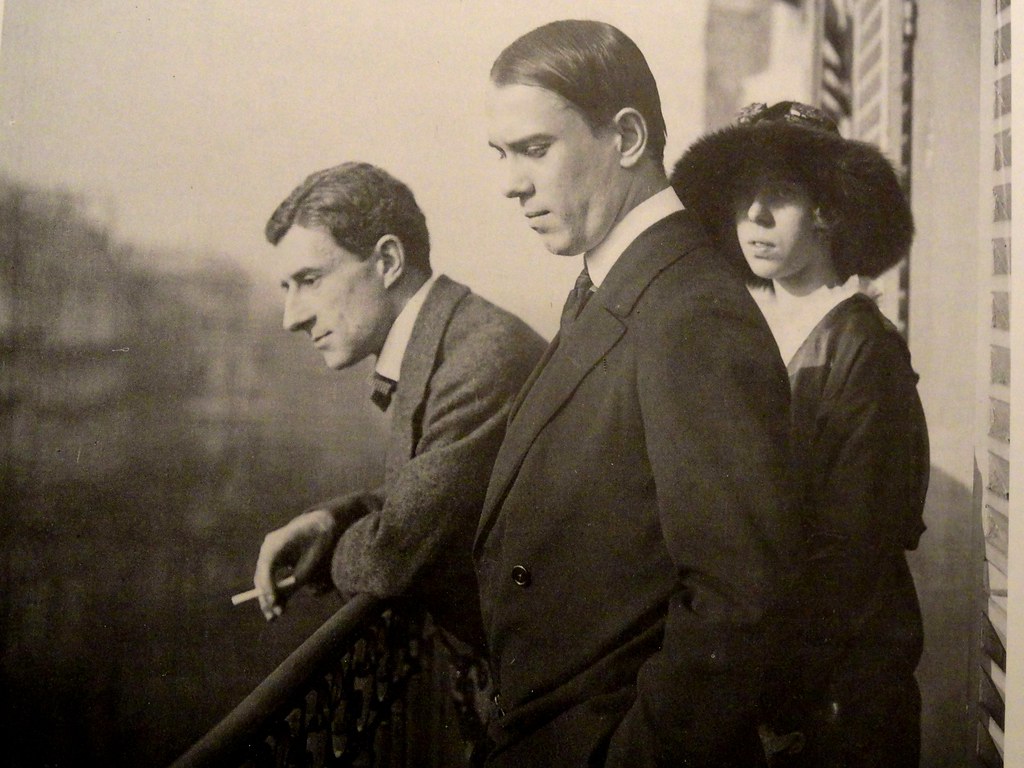

| Debussy and Stravinsky, 1910 |

On the centenary of Debussy's death, "Debussy and Beyond", with the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican,, conducted by François-Xavier Roth. This was the highlight of an unusually well planned series, examining Debussy from different angles. Anyone can programme mechanical "greatest hits" programes, but from Roth and the LSO we can expect much more musical nous. In "The Young Debussy", we heard the influences that shaped him, In "The Essence of Debussy", we heard well known pieces and the less well known, like the Fantasie for piano and orchestra,. This series has been challenging because it didn't spoonfeed, but presentedthoughtful challenges for further listening and contemplation. For "Debussy and Beyond", there could be dozens of possible contenders, since Debussy's influence on modern music is so extensive. Debussy changed the game, no less. He paved the way for others, whose music is very diffrent from his own, and continues to inspire. This evening's programme focussed on large ensemble, and on major works that would often be the backbone of most concerts. It lasted nearly three hours, but was so rewarding that time passed all too soon.

Homage to Debussy and also homage to Pierre Boulez, one of Debussy's finest interpreters and champions, who was born seven years and one day after Debussy died. Much has been written about how Boulez's Livre pour cordes morphed, or didn't morph, over 20+ years, so it's not worth repeating, save to say that it is "mega string quartet" scored for 16 first and 14 second violins, 12 violas, 10 cellos and 8 basses. The four main groups are multiplied into many parts, creating intricate polyphonic textures. Onto this a panoply of techniques, for further variety. Yet the whole piece lasts under 11 minutes. It's a model of tightly woven concision - nothing extraneous - precision. Roth conducted the LSO, so it came over as chamber music, albeit on a grand scale, the players interacting with precison and grace. Not "impressionism", in the "mood painting" sense of the word, but finely detailed complexity, extending Debussy's tonal ambiguity and chromatic adventure.

Though there's ostensibly little direct connection between Debussy and Bartók, both were pillars of twentieth century music, and cannot be ignored. Many others might have been included, but for practical, logistic reasons, this concert focussed on works for very large ensemble. Bartók's Violin Concerto no 2 BB117 (1937-8) served to balance the other two big pillars of the programme, Stravinsky's Chant du Rossignol and Debussy's La Mer, with Renaud Capuçon as soloist.. Capuçon's long solo passages were played with style, contrasting well with the striking orchestral backdrop. Since the LSO has a commendable commitment to new music, this was followed by the world premiere of Ewan Campbell's Frail Skies (2017), another work for very large orchestra including piano. I'd hesitate to call it a tone poem, though there are images in the music that suggest the forces of Nature. Though the title suggests the sky, I thought of waves in an ocean, carrying thousands of minute particles carried in their wake. The piece moves in cyclic fashion beginning and ending with solo cello surrounded by larger, darker forces, traversing other cyclic patterns along the way. High woodwinds added lightness, somnolent strings and brass added density. No young composer could compress as much into a short work as Boulez did with Livre pour cordes, but at least new work is being written, and new composers are finding their way.

Debussy and Stravinsky knew each other well. The photo above shows them together during the 1910 Ballets Russe season in Paris in 1910, when The Firebird was performed. For this programme, François-Xavier Roth included Stravinsky's Chant du rossignol, loosely based on Hans Christian Anderson's tale about a nightingale and a mythical Emperor of China. Given that Debussy was fascinated with Japanese and Indonesian culture, this was an inspired choice, connecting Debussy's eclectic interests and the craze for "primitive" non- western art, which made Stravinksy and Diaghilev sensation. French orientalism, which has a long past, was to stimulate numerous artists and composers, from Ravel to Picasso, to Messiaen and beyond. Recently Roth and Les Siècles gave a concert in Paris, which iuncluded a gamelan orchestra (read more here). With Chant du rossignol, Roth and the LSO open out a whole horizon to explore. In purely musical terms, Chant du rossignol is also apposite because Stravinsky blends exotic colour with lyricism. The nightingale is no Firebird, but its fragility is its strength. A violin sings for the mechanical nightingale, its elaborate trills deliberately formal. The flute sings for the real nightingale, singing with freedom and inventivenss. The Emperor, for all his wealth, cannot compete. The music that depicted him was dark and slow - basses and low timbred winds and brass, and tam tam, against which the "nightingale" shone ever more brightly. Exquisite detail in this performance, even in small figures, like trombone ellipses and the sensation of breeze (harps, strings, brass) at the very end.

François-Xavier Roth has conducted Debussy La mer so many times that it's practically his trademeark. He's even constructed whole programmes around it (please read more here). This time it felt valedictory. After that outstanding performance of Chant du rossignol, it was good to pause and reflect on Debussy and his legacy. La mer never loses its magic but seems to forever reveal new depths. The ocean covers most of the planet : different in different parts of the world, but always developing. A metaphor for music !

Saturday, 24 March 2018

Claude Debussy plays Debussy

Today, 100 years ago Claude Debussy was still alive.... Tomorrow marks the 100th anniversary of his death. I'll be hearing La Mer with François-Xavier Roth and the LSO at the Barbican, (Please read my review HERE) exploring Debussy's legacy. Boulez ! Stravinsky ! Ravel ! Messiaen ! and more.... Please see my other posts so far on Roth's Debussy series Young Debussy, Essential Debussy and Eclectic Gamelan Debussy. . Beware music histories which think modern music started only with Schoenberg and his devilish ways. All music is modern in its own time, and Debussy perhaps even more revolutionary in his way than most. Even after all this time, some still can't get Pelléas et Mélisande. But that's OK. That made it easier to grab good seats at Glyndebourne this season. It will be intriguing to see what master symbolist Stefan Herheim does with it. Below, Claude Debussy plays Clair de Lune, recorded very early on.

Friday, 23 March 2018

Glière The Red Poppy and Soviet non-realism

| The Harbour Scene in Glière's The Red Poppy |

Glière's The Red Poppy is set in China. Nothing unusual about that given western taste for exotic locales. Significantly, Turandot premiered in 1927, around the same time as The Red Poppy. Since a huge part of Asia was in fact part of the Russian Empire, it was perfectly natural for Russian composers and artists to incorporate "eastern" themes. Hence Borodin's Prince Igor, and much else. Yet there's more to The Red Poppy. It's poltical, and connects to a wider context of Soviet expansionism. The film, Storm over Asia (Vsevolod Pudokin, 1928) depicts a Mongolian herdsman mistreated by the British (generic capitalist) who eventually drives them from his land. The timing of The Red Poppy is worth noting. It's no accident either that the title is "red" poppy, since the "white" poppy produces the opium which caused the Opium Wars and the Unequal Treaties. China was in the throes of modernizing after thousands of years of feudalism, and the young Republic forced to call on help from outside. The Chinese couldn't really rely on western powers who had an interest in keeping China subservient, so they called in the Soviets. The Chinese Communist Party was minute, founded only in 1921, so it didn't seem a threat. But by 1924, Comintern had such influence that it could organize massive strikes in the main Treaty Ports, threatening the control of western powers. The leader of the Comintern in China was codenamed Borodin, a name familiar to many Chinese since his music was well known in China. Hanns Eisler's elder brother was also involved, lower down the scale. The Chinese soon got rid of the Comintern, but eventually the CCP took hold.

Glière's The Red Poppy depicts the harbour in a Treaty Port (as sen in the photo above, taken from the original production). Coolies, working on a pittance, are unloading goods for foreigners and the rich. In the Bratislava production the cargo is marked "From the USA" and contains guns. The workers are mistreated, not only by western capitalism but by Chinese collaborators, depicted - alas - like Fu Man Chu stereotypes. Glière incorporates many different musical styles to emphasize the contrast between cultures - foxtrots and jazz for the capitalists, bizarre pastiche Chinoiserie for the Chinese, and The Internationale for the Soviets and "good" Chines partisans. The original, being a ballet, contains numerous set pieces for dance, including passages where notes flutter breathlessly, so the dancers do a lot of en pointe, their feet arched as if they had bound feet (another western stereotype of Chinese culture). In ballet, dance tells the story, so plots don't need much depth. A Chinese nightclub dancer called Tai-Choa notices how nice the Soviet sailors are (they have a famous dance number). There are "Malay" dancers too, who have no function but to add another element of exotic soft porn - "Malays" no real Malay would recognize. In a protracted dream sequence, induced by smoking dope (as stereotype Chinese were expected to do), Tai-Choa finds herself in a temple with a giant Buddha. Demons dressed like generals in Beijing opera threaten her, but she's saved by good guy warriors in white (!) commanded by a Chinese partisan. The Chinese villian tries to get Tai-Choa to poison the Soviet Captain (whom she loves) but she won't do it. The temple/courtyard is raided and the Captain and his men enter. The Chinese villain raises his gun and shoots, but Taï-Choa sees what's happening and takes the shot, and dies.

Thursday, 22 March 2018

Anna Clyne, Benjamin Britten Violin Concerto : Oramo BBCSO

Sakari Oramo conducted the BBC SO at the Barbican last night : Anna Clyne and Benjamin Britten Two British composers, one a distinctive new voice, the other represented by a work which in recent years has found its true place in the canon. Heard together with a particularly fresh, vernal Beethoven Symphony no 6, this made a satisfying evening.

This was the UK premiere of Anna Clyne’s This Midnight Hour, first heard in Paris in 2015. Quality, in Anna Clyne’s case, gets her ahead, not her gender. She’s so original that the patronizing tag “female composer” is an insult. What is “female” music anyway. This Midnight Hour is ambitious work on a grand scale, though compact and precise. Rushing figures fly forwards, quite ferociously, leading to a passage of surprising clarity. Very rich sounds - especially the low strings - suggest dense textures, carefully defined. From moments of near-silence, pounding figures push forward, aletrnating with sudden lyrical passages. Winds and brass blow ellipses that seem to probe space. Two staccato thunderclaps, and the music swirls into fast paced turbulence, whipped by ellipses of high-pitched woodwinds. More combinations of quietness and explosive staccato, then a long passage of almost Romantic lushness, evoking the sounds of Spain. A long-held single note (bass trombone), evolves into nocturnal fanfare. A sudden crash on timpani, an abrupt end, like an exclamation point. Later I realized that this is a reference to a poem by Juan Ramón Jiménez which Clyne was responding to. “La musica; mujer desnuda,corriendo loca por la noche pura!” (The music: a naked woman, running madly in the pure night) . Apparently there are also references to Baudelaire’s Harmonie du soir (“Le violon frémit comme un coeur qu’on afflige,”), but This Midnight Hour was impressive even if I didn’t get that other level. There's no rule, whatsoever that poems have to be set word for word !

Although Britten didn't join the International Brigades in Spain, he believed passionately in their cause and was traumatized by Franco's victory. Heartsick, Britten feared that Europe would become engulfed in fascism, and needed to get away. His Violin Concerto is a product of that period of intense despair. Britten and Pears left Britain in April, 1939, when war seemed far away, and returned at some danger during hostilities to help the war effort as non-combatants. Those who have never heard his Violin Concerto may have thought him a coward but do not realize that it takes moral courage to write a deeply uncomforting statement like this. Perhaps only now can we appreciate its place in the canon of major works by a composer who thought more deeply about society than most.

From a hushed string introduction, the violin (soloist Vilde Frang) rose, against an understated but ominous background of percussion and brass. Despite the lyricism of the violin line, the idea of war lurked, with menace. Hollow pizzicato suggested agitation. The second movement has the character of nightmare scherzo, a battery of strings, brass and percussion battling with the violin, which remains detached. Oramo shaped the tumult carefully bringing out the huge, angular blocks of sound, booming bassoons, spikey details in the strings, rumbling drums, creating contrast with the violin. In the cadenza, Frang's pristine style lit up the dizzying diminuendo : not a defeat so much as "tactical withdrawal". In the passacaglia, descending notes from the brass moved in careful procession. Now the violin line was haunted by other strings, mumuring as if heard from afar. Eventually an anthem builds up, the brass no longer against the soloist, but leading forwards. Tense, brittle figures suggested gunfire, but the violin remained uncowed. A particularly full-throated tutti section, almost a chorale, violin and orchestra united in common cause. From the strings, a good suggestion of guitars : the ghosts of the dead in Spain, rising again, led by the violin, marching quietly onward.

A truly "pastoral" Beethoven Symphony no 6, unusually fresh and vernal, which worked well in connection with Britten's Violin Concerto. Perhaps the storm wasn't as overwhelming as usual, but the sense of revitalization Oramo found after it more than compensated. After the storm, the peasants are revitalized. Like the fallen in Spain, they will not be defeated.

Tuesday, 20 March 2018

Jurowski's Journey : Stravinsky The Fairy's Kiss

|

| Bronislava and Vaclav Nijinsky with Maurice Ravel, Paris : Photo: Igor Stravinksy |

Vladmir Jurowski's Stravinsky Journey with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall continued with Stravinsky's The Fairy Kiss, (Le baiser de la fée) framed by Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto no 1 in B flat minor (Daniil Trifonov) and extracts from The Sleeping Beauty. For me, the big draw was The Fairy's Kiss, fashionably maligned in its time, not least thanks to Diaghilev's disdain for Ida Rubenstein, a lovely celebrity but nowhere near the league of the Ballets Russe, and the fact that it was chreographed by Bronislava Nijinsky, who had followed her brother away from Diaghilev circles. Jurowski has a thing for the piece, having programmed and recorded the Divertimento in the past, so I was keen to hear what he would bring to it. Unusually snow bound conditions - for Southern England - might have added vaguely Russian atmosphere, but kept many of us trapped (we had 10 centimters, for the first time in years) but the concert was broadcast on BBC Radio 3. Luckily, weather was fine last night for Ensemble Intercontemporain at the Wigmore Hall - read more here.

Congratulations to Jurowski and the LPO for having the courage to pit Stravinsky's Fairy's Kiss against the ever-popular Tchaikovsky Piano concerto no 1. While Trifonov was reliable, this is a piece which needs more than reliability to reveal itself. Not that most punters care, as long as it sounds familiar, without any special insights. Part of the Fairy's Kiss "problem" is the plot, or lack thereof, but for Stravinsky himself the ballet was "an allegory of a man marked out from his fellows, unable to join in their life" : the role of an artist, whose destiny is to fulfil his gift, even if it means being alone. In 1928, that ideal was pertinent to Stravinky, living in exile, surrounded by change. In Tchaikovsky, he saw a quintessential outsider, forced to hide his true identity in a society where being out meant death. In musical terms, this applied too to Stravinsky, not because he was reverting to Tchaikovsky, but because he didn't want to be constrained by style, or by market forces. It's perhaps ironic that chreographers - Balanchine, Ashton, Macmillan, Ratmansky - have found more in the music than many listeners.

Rustling strings suggested the snowstorm in which the story begins, but typically Stravinskian winds delineated the narrative, leading onwards, then pausing tenderly. Perhaps one might imagine a vulnerable infant who might otherwise die. The pace picked up, winds and brass joining. Lively dotted rhythms, ideal for dancing to, outbursts of bassoon, flute and brass suggested a wild but cheerful procession, the horns adding a "peasant" touch. The baby grows up happily enough in the village, as the music suggests, but on the eve of his marriage the fairy returns, disguised as a gypsy. Tchaikovsky, who entered a mariage blanc may or may not have intuited Hans Christian Anderson's dilemmas about sexuality, but for Stravinsky, this turning point seems ms more artistic than literal. The music abounds with lively figures, ideal for dancing to, offering a choreographer many inentive opportunities. A single violin appears, then a woodwind : two figures, one seductive, once youthful. Eventually, a hush fell over the music, suggesting mystery. Perhaps the boy is enchanted, as the Fairy claims him for her own. Not such a bad fate, for an artist.

Ensemble Intercontemporain Wigmore Hall Birtwistle Carter

At the Wigmore Hall, London, music for wind quintet by Harrison Birtwistle, Elliott Carter, Heinz Holliger, John Cage and Blaise Ubaldini. with members of Ensemble Intercontemporain - Sophie Cherrier (flute), Martin Adámek (clarinet), Jens McManama (horn), Didier Pateau (oboe) and Paul Riveaux (bassoon). Wind quartets are great for sonorous harmony, but wind quintets are stranger beasts. The horn changes things, but that in itself opens out intriguing new possibilities. Composers with a quirky frame of mind can do very interesting things. I'd come to hear Harrison Birtwistle's Five Distances for Five Instruments (1992) a piece that needs to be heard live since it plays with space and distance. The work begins conventionally enough with the flute, singing freely, the bassoon answering. Will a pattern emerge ? In the middle stands the horn, breaking up symmetry. I was delighted that from where I was sitting, I couldn't see the horn, but heard it poking its way into the ensemble. The other instruments call to each other in different pairings, but the horn interjects, pushing each instrument to operate as an individual. They call out into the performance space, as if trying to get away. Eventually some sort of equilibrium is found: horn and bassoon fall into step together and the others follow and a pattern is restored. A short but extremely pithy piece, a typical Birtwistle puzzle.

This whole programme seemed to have been devised like a puzzle of interconnecting symmetries and non-symmetries. Bassoon (Paul Riveaux) and horn (Jens McManama) returned, singly, with Elliott Carter's Retracing for bassoon (2002) and Retracing II for horn (2009). Hearing both together demonstrated the individual nature of each instrument. The bassoon lends itself to the virtuoso challenges of a very short piece, the horn needs more time to "breathe". The oboe (Didier Pateau) starred, too, in Heinz Holliger's Sonata for oboe (1956-7), a joyous early piece, in which Holliger shows his love for the instrument and its capabilities. Flute (Sophie Cherrier) and clarinet (Martin Adámek) get their moment too, with Elliott Carter's Esprit rude/Esprit doux (1984). Embedded cryptically into it are the letters of Boulez's name. "Two personnages", as Pierre-Laurent Aimard, has described the way the two voices interact in counter to each other, "like in Bach".As Paul Griffiths writes in his programme notes, "This four note set... has the useful property that any interval can be derived from it (reappearing) in its original form to close what might be regarded as a four minute scene between two characters, or between two characters of the one".

To conclude, John Cage's Music for Wind Instruments (1938) and Blaise Ubaldini In the backyard (2017) . The former is a relatively straightforward piece which features first different sub-groups, then brings them together for the finale. Ubaldini's piece picks up on the cheeky good humour of Carter and Birtwistle's aphorisms. the players grunt and stamp their feet, their bodies supplying percussion. Five instruments with added extras, I guess.

Sunday, 18 March 2018

Ollie's back ! Knussen Busoni Brahms

|

| Oliver Knussen, Jukka Harju, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra |

Ferrucio Busoni does not fit any neat pigeonhole. Busoni believed that “music was born free and to win freedom is its destiny”, and that it was just in its infancy as an art form. Busoni envisioned the opening out of horizons. Just as the world changes, culture cannot stand still, and music changes with it. Although his own music isn't wildly radical, he paved the way ahead for others. His theories about music and culture may prove to be his legacy. No less than Edgard Varėse called him “a figure out of the Renaissance”, who “crystallised my half formed ideas, stimulated my imagination, and determined, I believe, the future development of my music”.

Busoni and Knussen have much in common. Indeed, understanding Knussen's life-long interest in Busoni explains a lot about what makes Ollie tick. Busoni's Rondo Arlecchinesco is based on his opera Arlecchino. Arlecchino, or Harlequin, is one of the standard Commedia dell'arte figures, the archetype of traditional Italian theatre. He's a servant, but not servile, so is depicted as a clown who subverts the pretensions of his masters. Leporello before his time ! Busoni places Arlecchino centre stage, the four parts of the opera depicting different aspects of Arlecchino's persona. Quicksilver figures introduce the Rondo, soon developing into fanfare, from which brooding, surging figures emerge. Knussen brings out the cheeky inventiveness in these figures, so when the staccato march resumes, complete with militaristc horns, the figures seem to fly, irrepressibly away from the constraints of control freakery which militarism represents. The bassoons and lower brass blow raspberries at the horns : disorceder poking fun at order. A voice sings "Lalalalala!", Harlequin's defiant song of freedom. Though the brushes may beat on the drums, our anti-hero cannot be suppressed. Significantly, Arlecchino was written just before the 1914-1918 war and premiered during the hostilities. Knussen's a Harlequin, too, in his own inimitable way. Who else could have written operas like Where the Wild Things are and Higgelty-Piggelty Pop !, which are by no means children's operas though they're based on Maurice Sendak. Please read my analysis of these operas HERE (Faith in Food) and HERE.

The fluency with which Knussen conducted Busoni's Nocturne Symphonique demonstrated a mature understanding of the darker mysteries of Busoni's idiom. Not for nothing that this preceded Knussen's own Horn Concerto, op 73, 1994/5, soloist Jukka Harju) which he has said "assumed more and more character of a Nachtmusik (in a Mahlerian sense)" as he worked on it. Short bursts of sound pop up, bright and alert. The horn enters, long calls weaving and moving , the orchestra commenting in brief explosive outbursts. Bright light winds and brass sparkle around the deeper timbre of the horn as the music enters a new and almost sinister phase, bassooons and contrabassoons rumbling menace. The horn line rises, as if searching direction by reaching into the space around it. Near-mayhem builds up around it, but the horn persists, despite ominous crashes of timpani. The horn continues reaching out, at first alone, then led on by muted horns and trumpets. The horn calls, met by crashing cymbals - the clash of metal against metal - but the horn has the advantage since it breathes "alive" as it's being played by human breath. Over the last 25 years, Knussen's Horn Concerto has been done so many times, it's almost standard repertoire, and for good reason.

As a teenager, Knussen looked like Claude Debussy's secret twin. Now he's in his 60's, he resembles Johannes Brahms. But that's not why he ended the Helsinki concert with Brahms Symphony no 2 . Musically, it connects with Busoni's Nocturne Symphoniue and with Knussen's Horn Concerto and links them all to much more ancient sources that might lie in European folk traditions, where dense forests are metaphors for the psyche, and fairy tales a language for coping with mysterious forces. "Aha !" I thought, "the spirit of Maurice Sendak!" At moments I thought I could hear echoes of Brahms Lullaby, which is perfectly pertinent. Knussen's Brahms is sometimes unorthodox, but this time he was conducting to the manner born, the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra playing with emotional depth.

Saturday, 17 March 2018

Christa Ludwig Champagne Birthday

| ||

|

Thursday, 15 March 2018

Pubs and the British choral tradition - The Gluepot Connection

The Full Heart is Peter Warlock's earliest choral work, dedicated to the memory of Carlo Gesualdo, an interesting choice of role model for the young Peter Heseltine who was but 21 when he sketched the piece. The Gesualdo connection probably relates more to musical form, for the piece employs finely parted chromatics, creating a rapturous work that seems to span centuries. "O, my companions, Wind, Waters, Stars and Night". The text is by Robert Nicholls, invalided from the Somme, and later a socialite whose friends included Aldous Huxley. Heseltine heard Frederick Delius's On Craig Ddu (1907) while still a student at Eton, and went on to champion the older composer. The two pieces complement each other, though Warlock is more stylish. Beautifully balanced singing from the Londinium Chamber Choir keeps texture clear and clean. Warlock's The Full Heart is a stand out, on its own worth the price of the CD.

Warlock and Moeran were born in the same year, but had different backgrounds, Heseltine's influences more esoteric and international. He didn't like the John Ireland focus at the Royal College of Music and encouraged Moeran to develop further. On this recording we hear Moeran's six Songs of Springtime (c. 1931) to poems by Shakespeare and his contemporaries. Warlock amd Moeran were close, and in this set Warlock's influence is clear : more polyphonic inventiveness built on Renaissance models, yet distinctively of its own time. These Warlock and Moeran settings shine out out in comparison with the more conventional John Ireland songs, The Hills and Twilight Night. The Hills, written to mark the Coronation in 1953, to a poem by James Kirkup, is chastely hymnal, while Twilight Night,

to a poem by Christina Rossetti, while Victorian, is rather more potent. Two people meet clapsed "as close as oak and ivy stand". They may never again meet "in the accustomed way" but that secret encounter is not erased. Ireland's setting is straightforward, but the meaning of the text could hardly have been lost on the younger moderns, like Warlock and Moeran, in the more liberated 1920's.

Andrew Griffiths' erudite booklet notes give extensive detail on other habitués of the "gluepot", with so many cross-references that one could probably draw up a flowchart. He quotes Michael Tippett on the "anti-Britten" clique at the George, ".... a cabal of composers who were trying to debunk Ben (Britten) or undermine his reputation.....they all had great chips on their shoulders and enetrtained absurd fantasies about a homosexual conspiracy in music led by Britten and Pears". Bigots will always find excuses, hence the homophobia, but the real threat Britten posed was not his sexuality but the fact that his music didn't conform to the assumptions of what "British music" should be. Frank Bridge opened his horizons to Europe, and WH Auden and Colin MacPhee to the world. Britten was original, and successful, which created resentment. Britten won the commission for the Coronation of 1953 with Gloriana, in which Queen Elizabeth I sees through sycophancy and status games. This didn't go down well with some, and for some Britten is still too "modern", though his influence has nurtured whole new generations of British composers and musicians. Britten didn't do the Gluepot, but he is relevant in context. He, too, drew inspiration from polyphony and Early Music, as any study of Gloriana will demonstrate.

The Gluepot "cabal" Tippett mentioned centred around Constance Lambert, his wife Isabel Nicholas, who later married Alan Rawsthorne, William Walton, and Elizabeth Lutyens and Alan Bush Most of these are represented in this collection, apart from Lambert who didn't write a capella choral work. Rawsthorne's Four Seasonal Songs (1956). The title is slightly misleading, since three of the songs refer to Spring. More multipart harmonics applied to 16th century texts ! In Lutyens' Verses of Love (1970) to a text by Ben Jonson, long lines elide, sounds shimmering. Walton's Where does the Uttered Music Go ? (1946) was written for the dedication of the memorial window of Sir Henry Wood in the Musicians Chapel in St Sepulchre's where Wood, as a boy, learned to play the organ. This disc also includes the premiere recordings of Alan Bush's Like Rivers Flowing (1957) with sinuous lines, and Lidice (1947) commemorating the massacre in Lidice by the Nazis. The mood is hushed, the lines swirling : a secular Requiem.

Another Gluepot regular was Arnold Bax. His I sing of a maiden (1923) has charm, but is eclipsed by his Mater ora filium (1921) a substantial (11 minute) masterpiece based on William Byrd's five-part Mass, beefed up for as many as 16 parts, embellished by what Griffiths calls "prodigious extremes of range" (cloaked in) "luscious, late Romantic harmony in myriad different textures". The voices of the Londinium Chamber Choir rise to the task, their voices glowing "Amen, Amen". It's as if a stained glass window were bursting into song !

Wednesday, 14 March 2018

Monday, 12 March 2018

John Eliot Gardiner LSO Schumann Berlioz

|

| John Eliot Gardiner, photo Sim Canetty-Clarke |

The start of a major Schumann series with John Eliot Gardiner conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican: Schumann Symphony no 2 in C major op 61 (1847) and the Overture to Genoveva with Berlioz Les nuits d'été, soloist Ann Hallenberg. Gardiner is one of the great Schumann conductors of our time, so the LSO are right on the mark, choosing him to head their Schumann series, which began with this concert, continues on 15th March and into 2019. A major series, whose importance cannot be overestimated. Perhaps we can hear Schumann all the time, but rarely at this level of excellence.

Gardiner's approach to Schumann is inspired by a deep understanding of the composer's aesthetic. It's a mistake to assume that period-informed performance means period instruments It has much more to do with understanding the composer's idiom and practices which might enhance performance dynamics. The LSO doesn't use period instruments, but achieves werktreue effects by other means. The players didn't sit down to play but instead stood up throughout. Immediately, you could hear the difference. You'd need cloth ears not to notice, even if you didn't know "why". Because the players were closer together, the sound was more concentrated, achieving volume without having to force the instruments, the sound projected from a few feet higher than usual, intensifying the interaction between players and podium. Chamber-like sensititivty, in a large (ish) ensemble. The musicians could move freely, flexing their bodies naturally, without the rigidity that comes from sitting down. This flexibility flowed through to the music, which felt direct and spontaneous, textures bright and clearly defined. Gardiner's Schumann is agile and alive, revealing the composer's true originality.

Gardiner preceeded Schumann's Symphony no 2 with the Overture to his opera Genoveva, which he began at around the same time as he wrote the symphony. The connections go deeper. The original folk tale on which Genoveva is based dates back to the Middle Ages. Indeed it’s the basis of stories like Snow White, for in legend, Genoveva lived in the forest, protected by animals and by her virtue. Significantly, though, Schumann rejected the medieval concept, choosing instead to base his opera on Friedrich Hebbel’s more psychological drama, published only four years previously. Schumann wanted a “modern” take on the story. As Hebbel said “Any drama will come alive only to the extent that it expresses the spirit of the age which brings it forth”. The Overture sets the stage, introducing the themes that will be developed more fully in the opera. It's marvellous, but listen to how it zooms into a chorale, and then into the opera proper, rather like successive proscenia in a theatre add depth to a flat stage. Schumann's doing dramatic perspective with music.

Schumann's Symphony no 2 begins with another brass chorale, which here came over without stridency, the "brassiness" muted and dignified, integrating well with the bassoons, winds and strings. How poignant the horns and winds sounded, evoking Nature, hinting at the deep sources of the Romantic imagination. Moving from sostenuto to allegro, Schumann then creates a wild scherzo where notes seem to fly in fiendishly complex patterns, though the themes are sharply defined. Schumann 2 is unusual, because it mixes serene passages with oddball quirks. The last movement is sublime, but it's undercut by the moody bassoon from the Adagio, which Schumann told a friend was when he heard his "half sickness" calling him. Yet he had a "special fondness" for this strange melancholy , which infused even the happiest moments of his life. Who but Schumann could have written Dichterliebe as a wedding gift after having struggled so long to win Clara from her father?

Throughout this symphony there are oblique references to Bach and especially to Mendelssohn whose Midsummer Night's Dream music casts a magical glow on the Adagio. The assertive, affirmative confidence of the final movement seemed to come straight from the spirit of Beethoven.

Genoveva and Lohengrin both premiered in the summer of 1850. Wagner disparaged Schumann, as he disparaged Mendelssohn (Schumann’s hero). Since Wagner’s opinions were influential, Genoveva has been eclipsed, and most late Schuman undervalued because it doesn't fit the Wagner ethos But Schumann’s ideas on music and music drana stem from sources earlier than Wagner, and might have developed an alternative path had he continued writing after the age of 45.

Between Schumann's Overture to Genoveva and his Symphony no 2, Berlioz Les nuits d'été op 7 (1841). Gardiner is also a great Berlioz conductor : remember his Damnation of Faust last year ? (read my piece here). The immediacy of Gardiner's style adds punch to the song cycle, enhancing dramatic tension. Ann Hallenberg was a good soloist, not especially French, but in the context of a Schumann series, that's perfectly apt.

This concert was also broadcast live, part of the LSO live initiative. This itself is news, since it enables the LSO to reach international audiences online who might not otherwise be able to attend concerts, even when the LSO goes on tour. This particular concert seems to attracted less than the number who logged in for Bychkov's Mahler symphony no 2, but that's fair enough. Mahler is box office, while Schumann and particularly up-market Schumann is more esoteric. It will be interesting to see what the next live stream draws on April 11th (Mahler 10, Simon Rattle, Michael Tippett The Rose Garden) The economics of livestream are hard to measure. This concert reached about as many as would be seated in the Barbican, but will continue to attract viewers on Youtube for a longer period. The knock-on effect should also be felt in CD/DVD sales. Long term, streaming enhances the profile of the orchestra, and reaches a wider public.

Sunday, 11 March 2018

"New" Schubert Schwanengesang - Florian Boesch, Wigmore Hall

Schubert Schwanengesang, D957 (1828) with Florian Boesch and Malcolm Martineau at the Wigmore Hall, London. Schwanengesang isn't Schubert's Swan Song any more than it is a cycle like Die schöne Müllerin or Winterreise. The title was given it by his publishers Haslingers, after his death, combining settings of two very differet poets, Ludwig Rellstab and Heinrich Heine. Wigmore Hall audiences have heard lots of good Schwanengesangs, including Boesch and Martineau performances in the past, but this was something special.

Since Schwanengesang is not a song cycle, there's no reason why song order can't be altered. Boesch and Martineau began with Liebesbotschaft, following it with Frühlingssensucht and Ständchen, forming a bouquet, where the songs complemented each other. This meant that Boesch could focuss on emotional finesse. We're so used to good baritone performances that it's easy to underestimate the delicacy in these songs, but Boesch, despite the firmness in his timbre, achieves an almost tenor-like freshness, which is very moving. Martineau's opening notes in Ständchen floated gracefully : you could imagine the plucking of lute strings on a warm summer evening. Boesch has an uncanny ability to sound much younger than he is, without sacrificing the poise that comes with maturity, but what was most impressive here was the way he conveyed the innate intimacy in the songs. The words were shaded as if they were spontaneous, private exchanges. Nothing "troubadour" here. Real lovers, real feelings.

Then in flew Abschied. A farewell so early in the journey? The vigorous figures in the piano part suggest speed and forward thrust. But a clue is hidden in the last strophe. Not all the stars in heaven can replace "Der Fensterlein trübes, verschimmerndes Licht". Boesch shaped the phrase deliberately. Beneath the blustery surface, we glimpse once again the intimacy we heard in the first three songs, and feel the loss more strongly. When Boesch sang the first line of In der ferne, "Wehe, den Fliehenden, Welt hinaus ziehenden", my blood ran cold. Suddenly it hit me why that line spans two rhyming phrases. The two songs Abschied and In der Ferne form a pair, one pretending denial, the other unmasked grief. Thus the logic of grouping them with the turmoil of Aufenthalt and with Kreigers Ahnung, which in the Haslinger edition comes as the second song and here forms the end of the Rellstab settings. In Kreigers Ahnung, the poet is on a battlefield. He's afraid, his heart heavy with foreboding. And what thought gives him comfort ? "Herzliebe - gute Nacht!", sang Boesch, his voice ringing first with tenderness, then with a kind of haunted resignation, the song quietly fades, and the poet falls asleep.

Boesch and Martineau's re-ordering of the Rellstab songs makes sense, musically and in terms of meaning, bringing out depths in the material which can be overlooked in comparison with the more sophisticated Heine songs. No-one knows what Schubert might have done, had he lived longer. How much more of Heine would he have set ? And would more Heine have developed him as a composer, in the way that Schumann was shaped by Heine ? Boesch and Martineau paired Das Fischermädchen with Am Meer, but the connections are deeper than images of the sea, which in any case is a metaphor for emotion, which the Fischermädchen is right to fear. The lilting lyricism of the first song gives way to the more disturbing undercurrents of "Der Nebel stieg, das Wasser schwoll" in Am Meer. Boesch's voice rose for a moment before receding backwards, like the ebb and flow of a tide. The two pairs of strophes mirror one another. Am Meer thus flowed into Ihr Bild, with its dark piano chords and penitential pace. Ihr Bild flowed into Die Stadt. In both texts, the imagery is almost supernatural. In Die Stadt the piano line is almost impressionistic, a painting in sound. Only in the last verse does the mood lift, "leuchtend vom Boden empor", Boesch's voice is suddenly defiant, but the mists descend again.

Thus we were prepared for the final pairing, Der Doppelgänger and Der Atlas, first and last in the Haslinger Heine set and here heard in reverse order. The pattern of sombre pace and short-lived protest that has gone before returns in Der Doppelgänger but hearing Der Atlas last restores the balance in favour of protest. Martineau defined the piano part so it felt monumental, and Boesch's singing took on majesty. Like the Doppelgänger, Atlas has lost what made him happy, and is doomed to suffer for eternity. He is cursed, but he is strong and will not crumble. Boesch and Martineau's song order has musical and textual insight, and deserves great respect. This is a refreshing new way of listening to a group of songs that otherwise can sometimes, in less capable performances, seem uneven. Seeing microphones in the auditorium suggests that a recording will be in the offing, and well worth getting even if you already have rows of Schwanengesangs, or even the previous recording Boesch and Martineau made for Onyx a few years back. This unique performance is in an altogether different league than most.

In the intermission before the Rellstab and Heine songs Boesch and Martineau did Grenzen von Menschheit D 716, Meeres Stille D 216 and Der Fischer D225 - which also form a mini-cyle of their own amd fit in very well with the songs that make up Schwanengesang. At the very end, though, Boesch and Martineau found a way to incorporate Die Taubenpost, D 965 A, Schubert's setting of a poem by Johann Gabriel Seidl, which the publishers Haslinger added to Schwangesang but which has little connection, otherwise. Boesch's face lit up in a broad grin, and he danced a cheerful shimmy before he started to sing, banishing the ghosts of loss and despair. Yet again this made musical sense, since like Abschied, the carefree mood in Der Taubenpost belies its message : the dove's name is Sehnsucht, but, being a bird, it doesn't know what that means.

Saturday, 10 March 2018

Thursday, 8 March 2018

Janáček From the House of the Dead, ROH and memories of Chéreau

|

| Scene from From the House of the Dead, Patrice Chéreau 2007 |

Mark Wigglesworth's conducting certainly played up the violence, and rightly so, since there's nothing cute about a society that needs gulags to keep people under control. Luckily for me, I learned this opera audio-only, from the Vaclav Neumann recording, rather than from Mackerras, so I think of it in terms of the music first. The first time I experienced the opera live was when Perre Boulez conducted the production directed by Patrice Chéreau : a historic event in many ways, impossible to forget. Boulez conducted with an unnerving intensity: red hot holds nothing back but ice-cold suggests invisible horrors too dangerous to contemplate. The tragedy of human suffering, so fundamental to Janáček's vision, grows ever more powerful in contrast. From the House of the Dead is actually more humane than some assume. Janáček cared about people. As Chéreau pointed out, what really pervades the opera for him is its implicit humanity. Under the harshness and violence flows surprisingly strongly a sense of “compassion”, as he puts it, which runs like a hidden stream throughout the opera, surfacing at critical junctures. It is also totally non-judgemental. Neither murderers nor guards are held to account, they simply exist. Thus the famous phrase near the end, “he too was born of a mother”.

At a discussion session after the performance I heard in Amsterdam in 2007, someone in the audience (beware that type) asked Chéreau why he didn't costume the prisoners in orange, to protest Guantanamo Bay. Quick as a flash, Boulez said: "We are in Holland. In Holland, Orange is the Royal House". In a nutshell, the art of visual literacy : images mean different things. Chéreau's prisoners could have been Everyman in their drab garb, in a set dystopian in its abstraction. The prisoners engaged in pointless, repetitive work (building a ship in landlocked Siberia) but it doesn't overwhelm the stage. Instead there's an explosion when the bags of waste paper the men have been collecting blow up and scatter all over the stage: Substance now, waste no longer. This explosion coincided with a dramatic climax in the music. In a single striking image, the message is that men who have been thrown away by society are not detritus, whether they can fight back or not.

"Coherence", said Chéreau that eveing so long ago, "between ideas, music and drama, is the basis of interpretation". Stagecraft is not decoration : it is Gesamtkunstwerk, the drawing-together of different elements into a whole. Audiences often go for shallow productions because they are bright and jokey, but that isn't necessarily "what the composer intended". Warlikowski's production has a bit of everything. His thing for vivid jewel colours against black and white usually works extremely well, though less so in this case. Maybe ROH chose him to please the punters, so they can tell the difference between prisoners, guards and visitors (which, arguably, should be minimal, just as there often isn't much difference in real life). Huge structures dominate, which is a good thing as they suggest overwhelming forces intimidating small figures. It's a rather well-organized prison, probably not too remote, since there are a lot of outsiders here, including blow-up dolls. Presumably these suggest how society dehumanizes women, treating them as objects, which is perfectly valid and connects to the central idea that the men in this prison are "in the house of the dead". ROH wouldn't have dared show real women getting kicked about, and in any case no-one "should" need the details. London punters go berserk over two seconds of tit, glimpsed for a moment in an entirely appropriate context, so they can't be expected to understand that their own sensibilities are not more important than being moved by the suffering of others. The Prostitute (Alison Cook) as symbol, in bright-green hot pants cavorting chastely with the boys. (Or not so chastely, given that she looks 14.) Nothing wrong with that image per se since prostitutes are the "prisoners" of a messed-up world. Chéreau had the Eagle shot, but for a moment we glimpsed its glory. Maybe I missed Warlikowski's Eagle, but perhaps The Prostitute serves a similar function: she gets out alive.

Big names for the parts where older voices work well like Willard W White as Alexandr Petrovič Gorjančikov, Graham Clark as Antonic the Elderly Prisoner. Stefan Margita sang Luka Kuzmič, as he did in the 2007 run as did Peter Hoare, singing Šapkin. Pascal Charbonneau sang an impressive Aljeja. Ladislav Elgr sang Skuratov and Johan Reuter sang Šiškov. Alexander Vassiliev sang The Governor. As always, House regulars like Jeffrey Lloyd Roberts, Grant Doyle and the always-superb Royal Opera House Chorus were good and reliable. Nice dancers, too, writhing and twisting their (very attractive) bodies, expressing what is suggested in the music but which ROH probably needs to censor for fear of punter wrath. This production is not the best, but by no means is it the worst. But there is not a lot you can do with London audiences who can't be bothered to find out about a composer or an opera beforehand and insist on kitsch and circus. Inevitably that means compromise, which is not good for art.

Tuesday, 6 March 2018

Muhai Tang Shanghai Chinese Orchestra, Philharmonie de Paris

Muhai Tang and the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra have been touring Europe in a series coinciding with the Chinese Lunar New Year. Their concert at the Philharmonie de Paris is now online on the Philhamonie site. This is serious Chinese classical music, extremely well done, light years ahead of the sort of kitsch you get on TV and in some movies. Chinese opera dates back some 700 years, pre-dating western opera. Traditionally Chinese music was chamber music for private self-cultivation or folk/popular music for entertainment. Even opera orchestras were relatively modest, the emphasis on poetry, acting and singing. Large-scale Chinese instrument orchestras are relatively new, going back around 100 years. But consider that western orchestral tradition didn't come into its own until the late 18th century, and the extreme cultural differences that had to be overcome, it's quite some achievement how distinctive Chinese classical orchestras can be. All the pieces on this programme are modern works, adapting traditional themes and instruments, effectively creating an original new genre. Muhai Tang, like many of his players, is well versed in western music as well as in Chinese, which adds extra richness to performance. So listen to this concert, and watch it, too, because the filming is musically well informed, with close up focus on playing techniques you'd never see so clearly in concert hall conditions. You can focus on tiny, delicate sounds, like a single string reverbrating in near silence, and see instruments like the Chinese piccolo, triangle and snakeskin drums.

Appropriately, the programme began with Harmony, by Wang Yun Fei, featuring three Sheng players, followed by Wang's even more impressive Black Bamboo for long bamboo flute, pipa and erhu. The large flute has depth and volume, suggesting the gravity of bamboo trunks, whose wood is so strong that it can be used to build ships and houses. The lightness of the pipa and erhu suggeest movement and flexibility, even a sense of gentle swaying movement, familiar to anyone who's ever seen bamboos bending in the breeze. More imagery in Spirit of Chinese Calligraphy (Luo Xiaoci, orchestrated by Xie Peng), with zheng soloist Lu Shasha. A small bamboo flute calls, introducing the zheng, this one with magnificent depth and vigour. In the west, the term "calligraphy" means ornamental writing, but in Chinese culture calligraphy is an artistic form of expression. Brush strokes "speak": swift, sure figures moving rapidly across paper after a period of contemplation. Lu's playing is graceful and forceful, contrasted with the call of a small banboo flute. My friend's mother's calligraphy was firm and independent, resembling kapok trees, whose strong lines and angles are majestic, and whose fleshy red flowers spring from bare branches. Spirit of Chinese Calligraphy is abstract, but you can hear the individuality and decisiveness in the flow.

During the Qin dynastic period (221-206 BC), a concubine sacrificed herself to give courage to her Emperor in wartime. This story of love and duty is so powerful that it's inspired literature and opera. Here we heard an adaptation for modern Chinese orchestra which captures the drama. Its ferocity suggests the saga of non-stop warfare from which the first dynasty in recorded Chinese history emerged, and its majesty suggests the splendour of the imperial court and the love affair that led to tragedy. Three main figures form the core : pipa, jinghu and large Chinese drum. Around them the tumult of full orchestra, complemented by westen woodwinds, celli and basses. The pipa often resembles the sound of a human voice, so its cry is plaintive against the turbulence. More esoteric, Caterpillar Fungus (Fang Dongqing) arranged for an ensemble of mixed plucked strings including pipas, different types of zheng and qin (large moon shape bodied lutes). Percussive effects are made by beating hands on wood. The fungus grows on caterpillars and kills its host, though it has curative powers for humans. Part worm, insect and plant, it is mysterious. Thus the music is hybrid, with a character that could be adapted for western strings.

The Butterfly Lovers Concerto, based on one of the most famous legends in Chinese literature, was written in 1959 by He Zanghou and Chen Gang. Here we heard an adaptation for erhu with soloist Ma Xiao hu, which I think makes it sound more natural than the better known version for western violin. The erhu duets with the western cello, the "lovers" who cannot meet until released from mortal life. The zheng suggest airborne flight, the Chinese flute the idea of birdsong. Dancing Phoenix (Huang Lei) features the suona a high pitched horn. Soloist Hu Chenyun calls out, from behind the orchestra, duetting with a small mouth organ : song bird and strident phoenix in a forest of strings, winds and drums, until the souna takes off with a long protracted call, the orchestra strutting in its wake. Imagine if Messiaen had heard this !

Three "Landscapes", The Silk Road (Jian Jiping), Moonlit Lughou Bridge Before Dawn (Zhoiu Ziping) and Wedding Celebration from Tan Dun's Northwest Suite, the first and last spiced up with regional colour, such as the evocation of Muslim music, are eclipsed by the middlepiece where shifting textures and tempi create a sophisticated tone poem. Long serene lines mark the beginning, flowing string figures suggesting the movement of water and a thousand years of traders approaching Beijing. Drums and cymbals announce a wilder, freer section whose zig zag lines could suggest the sounds of Beijing opera. The theme then develops into a majestic swaying crescendo broken by plaintive solo erhu, played by the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra Leader. Then suddenly it breaks off, in silence. (The attack on the Lughou Bridge marked the start of the 1931-45 invasion when tens of millions were killed and made refugees. )

Sunday, 4 March 2018

Whipping up pogroms

Elsker Hverasndre (The stigmatized, or Love one Another), a silent movie about pogroms in Russia, made in Germany in 1922, by Danish director Carl Th Dreyer with a mainly Russian cast, still frighteningly prescient 100 years later. Hanna-Liebe Segal grows up in the ghetto of a Russian town on the Dnieper. For some reason her mother sends her to a Cristian school, which is odd since her older brother Jakov was cursed by their father for converting after he moved to St Petersburg and got "Russianized". When Hanna grows up she falls for a student revolutionary, Sasha, so she, too, heads off for St Petersburg. She lives with a Jewish family since her brother is passing for Russian. Jakov, a successful lawyer, recognizes secret police infiltrators among Hanna's friends, one of whom is Rylowitsch, who seems to hate everyone, Jewish, radical or Christian. After smashing the progressives, Rylowitsch poses as a mad monk, whipping up fear. "The Tsar is signing your land over to te Jews!" You'd think that might be a logical reason for dumping the Tsar, but instead, the peasants kiss icons of the Tsar and kill Jews instead. Then, as now, populist mobs are easily manipulated. Jakov goes back to the village when his mother dies and sees a ghost in a prayer shawl, walking through doors. Though he's a Christian, sincere enough to wear a cross, the mob kills him, too. The village goes up in flames, many are killed. Hanna's revolutionary boyfriend returns, and the pair head off for the Polish/German border....... Everyone's screwed when mobs run loose. Could a film like this have been made in Russia at the time ? And will such things happen again, to different communities, in different times and places ? Though the pace is slow and stylized, there are many good moments here. The ghetto scenes were filmed in a studio in Berlin, but based on real places in the ghetto in Lublin. Brother-in-law "Red haired Abraham" operates a machine that rocks the cradle while he works across the room. Mama Segal lays out her daughter's trousseau though Hanna has no intention of settliung down. The scenes in St Petersburg are in some ways even more poignant because they aren't artificial sets but real furniture and furnishings, new at the time, antique now. The family Hanna lodges with owns a keyboard iunstrument with no apparent backboard, unless it's built into the wall. Above the keys is a depiction of a lyre which must stand 2 metres tall. A world that's gone. Or does history repeat ? Plenty of Rylowitschs around, though they don't pretend to be monks. Please see my other posts on early film and on Carl Th Dreyer, using the label below, including his Der Vampyr and The Passion of Joan of Arc.