|

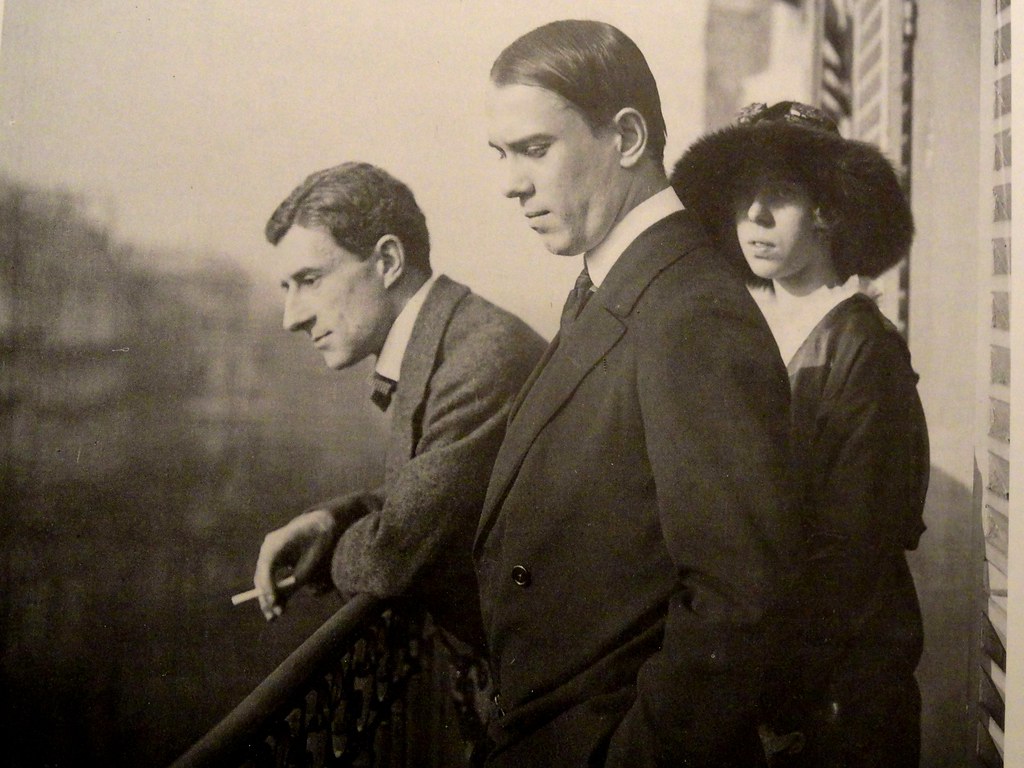

| Bronislava and Vaclav Nijinsky with Maurice Ravel, Paris : Photo: Igor Stravinksy |

Vladmir Jurowski's Stravinsky Journey with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall continued with Stravinsky's The Fairy Kiss, (Le baiser de la fée) framed by Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto no 1 in B flat minor (Daniil Trifonov) and extracts from The Sleeping Beauty. For me, the big draw was The Fairy's Kiss, fashionably maligned in its time, not least thanks to Diaghilev's disdain for Ida Rubenstein, a lovely celebrity but nowhere near the league of the Ballets Russe, and the fact that it was chreographed by Bronislava Nijinsky, who had followed her brother away from Diaghilev circles. Jurowski has a thing for the piece, having programmed and recorded the Divertimento in the past, so I was keen to hear what he would bring to it. Unusually snow bound conditions - for Southern England - might have added vaguely Russian atmosphere, but kept many of us trapped (we had 10 centimters, for the first time in years) but the concert was broadcast on BBC Radio 3. Luckily, weather was fine last night for Ensemble Intercontemporain at the Wigmore Hall - read more here.

Congratulations to Jurowski and the LPO for having the courage to pit Stravinsky's Fairy's Kiss against the ever-popular Tchaikovsky Piano concerto no 1. While Trifonov was reliable, this is a piece which needs more than reliability to reveal itself. Not that most punters care, as long as it sounds familiar, without any special insights. Part of the Fairy's Kiss "problem" is the plot, or lack thereof, but for Stravinsky himself the ballet was "an allegory of a man marked out from his fellows, unable to join in their life" : the role of an artist, whose destiny is to fulfil his gift, even if it means being alone. In 1928, that ideal was pertinent to Stravinky, living in exile, surrounded by change. In Tchaikovsky, he saw a quintessential outsider, forced to hide his true identity in a society where being out meant death. In musical terms, this applied too to Stravinsky, not because he was reverting to Tchaikovsky, but because he didn't want to be constrained by style, or by market forces. It's perhaps ironic that chreographers - Balanchine, Ashton, Macmillan, Ratmansky - have found more in the music than many listeners.

Rustling strings suggested the snowstorm in which the story begins, but typically Stravinskian winds delineated the narrative, leading onwards, then pausing tenderly. Perhaps one might imagine a vulnerable infant who might otherwise die. The pace picked up, winds and brass joining. Lively dotted rhythms, ideal for dancing to, outbursts of bassoon, flute and brass suggested a wild but cheerful procession, the horns adding a "peasant" touch. The baby grows up happily enough in the village, as the music suggests, but on the eve of his marriage the fairy returns, disguised as a gypsy. Tchaikovsky, who entered a mariage blanc may or may not have intuited Hans Christian Anderson's dilemmas about sexuality, but for Stravinsky, this turning point seems ms more artistic than literal. The music abounds with lively figures, ideal for dancing to, offering a choreographer many inentive opportunities. A single violin appears, then a woodwind : two figures, one seductive, once youthful. Eventually, a hush fell over the music, suggesting mystery. Perhaps the boy is enchanted, as the Fairy claims him for her own. Not such a bad fate, for an artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment