|

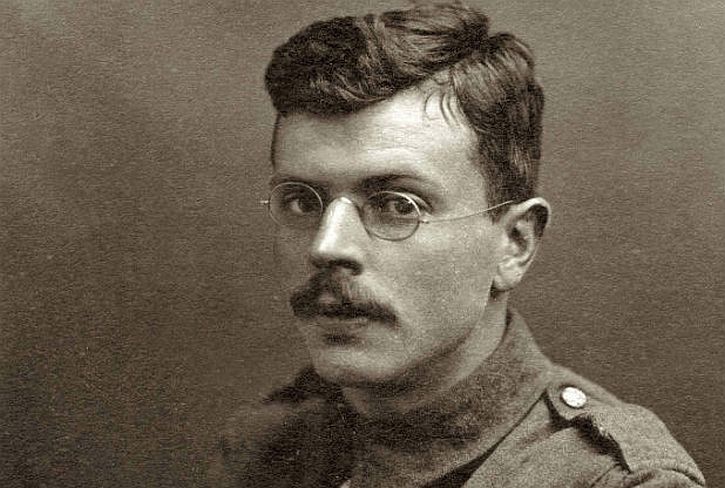

| W H Auden and Benjamin Britten |

Britten's Ballad for Heroes Op 14, 1939 for example. When I first heard the piece seven years ago (Ilan Volkov BBCSO, Barbican) I didn't understand it, but gradually it's grown on me. The disparity between the poetry of W H Auden and the doggerel of Randall Swingler is a problem, but Britten uses it with a certain degree of irony. Auden is an intellectual : Swingler a man of action (a Communist) but not so good with words. Auden opposes fascism, while Swingler's solution is to fight with more violence. Yet they trundle along together, with unison chorus and marching orchestra The contradictions in the piece provoke, just as the situation did. Therefore the piece is about a lot more than a simplistic conflict between pro and anti war. It should be noted that the Spanish Civil War ended in April 1939, with the triumph of the fascists and their Nazi allies, so the piece (which premiered at the end of April 1939) isn't about going to war so much as a realization that war alone cannot defeat the forces of evil. The title is "Ballad for Heroes", not "Ballad of Heroes", for the cause the heroes fought for had been crushed so cruelly that it was hard not to envisage the eventual triumph of Hitler, who enjoyed a lot more support, even in Britain, than some will now admit. Despite the annexation of Czechslovakia, and the Nuremberg Race Laws, Britain supported a policy of Appeasement. When Chamberlain announced "Peace in Our Time" there were many for whom the slogan rang false. Appeasement, for better or worse, encouraged Hitler rather than curbed him, which is why so many despaired. It is unfair to fault Britten for leaving in April 1939 since Britain was at peace. There are many ways of opposing war and the mentality behind it. War was only declared on 3rd September 1939 because Germany invaded Poland, not because of the regime itself.

Thus the funeral march which runs through the Ballad for Heroes, with a solemn relentless tread. The chorus intones brief lines, alternating with the orchestra, replicating again the idea of different forces being yoked together in common cause. A mood of greater urgency and alarm is introduced by dizzy figures in the orchestra (wonderful writing for winds) replicated in the wayward vocal line, Strident machine gun staccato, wild dissonance, surging lines lit by flashes of woodwind light. "A world of horror!" Then suddenly the tenor (Ben Johnson) emerges, uncovered and alone. His lines curl and snarl with menace. ""....and the guns can be heard across the hills like wa-a-aves at night". You could imagine his face contorting when he sings of "the stench of violence". The vocal writing here is sophisticated, spiralling diminuendos, words stretched and twisted in a style Britten would use later, in the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings and much more. "Hear, you numberless Englishmen, to remind you of the greatness here among you, ......to fight for peace and for truth!" words rather cogent given the context of the those months between the annexation of Czechoslovakia and Austria, and the outbreak of war.

Ivor Gurney's Gloucestershire Rhapsody was written between 1919, on Gurney's return from the battlefield, and 1920, shortly before he was incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital, where he died 15 years later. Although it was generally assumed that Gurney's late works were incoherent and unplayable, Gurney scholars Philip Lancaster and Ian Venables have edited them for performance, revealing their true value. The expansive lines soar, with an almost Elgarian spirit. One might imagine Gurney inhaling the fresh, pure air of Gloucestershire, and the exhilaration of being able to roam in his beloved countryside. So very different from the horrors of the trenches! Gurney's doctors believed that he was better off in hospital, but, when a friend smuggled in a copy of a map, Gurney traced his old hiking routes with his fingers, as if re-living what he had lost. This background is relevant, for this performance seems infused with a spirit of freedom, of endless open horizons and limitless possibilities.

Ivor Gurney's Gloucestershire Rhapsody was written between 1919, on Gurney's return from the battlefield, and 1920, shortly before he was incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital, where he died 15 years later. Although it was generally assumed that Gurney's late works were incoherent and unplayable, Gurney scholars Philip Lancaster and Ian Venables have edited them for performance, revealing their true value. The expansive lines soar, with an almost Elgarian spirit. One might imagine Gurney inhaling the fresh, pure air of Gloucestershire, and the exhilaration of being able to roam in his beloved countryside. So very different from the horrors of the trenches! Gurney's doctors believed that he was better off in hospital, but, when a friend smuggled in a copy of a map, Gurney traced his old hiking routes with his fingers, as if re-living what he had lost. This background is relevant, for this performance seems infused with a spirit of freedom, of endless open horizons and limitless possibilities.This "open vista" approach to the Gloucestershire Rhapsody may connect to Gurney's own hopes for the future. Significantly, the piece starts with the same first bars as Richard Strauss Also sprach Zarathustra - a dramatic opening, but with a twist. Gurney deliberately wanted to counteract "The Prussians" and what they stood for. Understandable for a man who served throughout the war, though Strauss wasn't fond of “Prussians" either, being Bavarian. The horns give way to a pastorale evoking the Gloucestershire countryside, with its rolling hills and spacious panoramas. To Gurney, past and present connected in seamless flow. The ghosts of prehistoric hunters, Romans, medieval farmers, depicted in a bucolic dance theme. "Two thousand centuries of change, and strange people". An ostinato section suggests both the heavy march of Time and the men of Gloucestershire marching innocently to slaughter on the Somme. Gurney said that what kept him going in the trenches was the thought of commemorating these men in poetry and music. A short, chaotic "war" section then gives way to a beautifully expansive theme, which might evoke a glorious dawn after a night of horror. It's Elgarian in its glory, but also Gurneyesque. In this new dawn, though time moves on, Nature returns, and possibly heals. The recommended recording is on Chandos's CD British Tone Poems, conducted by Rumon Gamba.

|

| Arthur and Kennard Bliss |

Morning Heroes starts with the Iliad, where the Trojan hero Hector returns as a ghost. The symphony begins with a long quotation describing Hector taking leave of Andromache, his wife. "Would you leave your children orphans, your wife a widow". The refrain in the chorus acts as a whip, goading the heroes to further sacrifice. Bliss follows this first movement with the turbulent "The City Arming". Are the populace so caught up in bloodlust that they forget

the human toll ? The third movement, "The Vigil", is based on Walt Whitman's Vigil Strange I Kept of the Field One Night and his By the Bivouac's Fitful Flame. Whitman's verse isn't easy to set as its flow doesn't lend itself to music. Wisely, Bliss uses spoken narration, augmented by chorus, singing the lines so they seem to sweep like flames whipped by wind. Orchestrally, this is perhaps the most expressive moment. The brief return to the Iliad, which follows, is thus put into context, like a look back on values one might no longer share. When the final movement returns to graphic depictions of the Somme, the connection is made between wars long past and more recent. Resolution, of a sort comes, where the chorus sings, followed by a wonderful but brief figure for oboe, and a brief resurgence of the pounding motif from the beginning. Muffled percussion, muted brass, the mens' voices singing with restraint, as if heard from afar, the women's voices almost spectral. Yet again the orchestra up, martial music cloaked with menace. Yet a wayward melody emerges and the voices grow stronger and at last, a measure of serenity at the end.

Thanks for bringing this to my attention, how lucky we are to have the BBC iplayer.

ReplyDeleteRegards