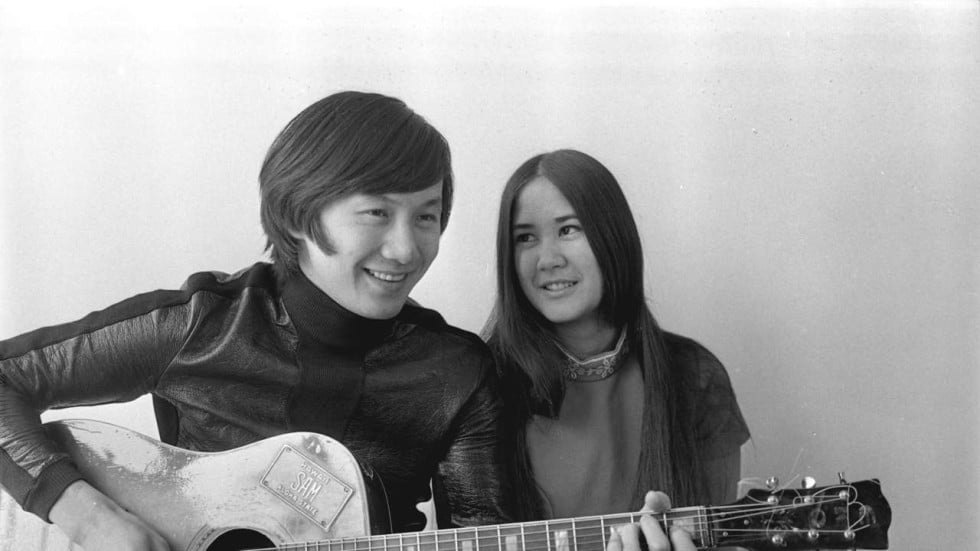

| Thielemann, Garanca, Dresden Staatskapelle, photo : Matthias Creutziger, Dresdner Neueste Nachtrichten |

First, let's consider what Thielemann has actually said about Mahler. Significantly, this quote was made during the Mahler anniversary year in 2010, when there was so much hype - often uninformed - that it's hardly surprising that someone should steer well clear on jumping on the celebrity bandwagon. "Mahler’s music lends itself most to those conductors” Thielemann reflects, “who know how to hold back, who are good at understatement. That doesn’t exactly accommodate my conducting style; I’ve not been terribly successful at that yet. The music of Mahler is already so full of effects, if you are tempted to add anything, you only make it worse. I admire those conductors who achieve that certain noblesse—which is what I desire to achieve, eventually. Not always to enhance something. I’m currently trying to wean myself off that in Strauss, actually…” Thielemann thus continues a solid three minutes on his fallibility as a conductor in Mahler, about trying to break habits and improving—a touching, beautifully honest moment. (source HERE)

Thielemann's actual words suggest that, far from being anti-Mahler, he had a far more accurate understanding of the composer than most. "Understatement" and "noblesse", as opposed to the kind of overwrought over-excess that became fashionable in the 60's and 70's, and has ever since dominated the way some audiences expect to hear Mahler. "Neurotic Mahler", shaped in part by Bernstein, Karajan and Ken Russell movies is valid in itself, but it is certainly not the only way to approach the composer. It's an audience thing. Conductors in the past, most of whom knew the background from which Mahler came, didn't subscribe to this image. Nowadays, thanks to the research of Professor Henry-Louis de La Grange, we know much more about Mahler's personality and creative processes, which has an impact on performance practice. "Understatement" and "noblesse" are a whole lot closer to Mahler than the self-indulgent image created in the 60's. If only audiences could learn to hear Mahler from these perspectives ! There is a whole lot more to Mahler than wham and bang.

Thielemann observed the subtle progressions that give the long first movement structure, and form the bedrock of the whole symphony. This movement does evolve like a panorama, each vista yielding to another, peak after peak on a vast horizon. Anyone's who has ever hiked and biked in the mountains as Mahler did will comprehend the sense of progression, and also the open-air expansiveness that Thielemann brought to it : the sense of freedom and endless possibilities, a purer, more rarified atmosphere, unpolluted by venal concerns. Strauss' Alpensinfonie, completed 18 years after Mahler 3 has that sense of adventure, but not quite the almost Brucknerian spirituality which Thielemann finds in Mahler. The previous evening I'd been watching Arnold Fanck's Der heilige Berg (1926) which merges Bergfilm with esoteric mysticism. The skiers achieve great feats on the snow, while the dancer Diotima (the Eternal Feminine) represents artistic ideals.

The Dresden Staatskapelle is a superlative ensemble, sleek and wonderfully agile. Beautifully judged details, well integated into the whole so the flow felt natural and organic. Big blocks of sound we can hear anytime, but less often this poetic sensibility. It's more difficult to achieve this kind of genuine purity than to blast away. A very authentic post horn, like you hear in the mountains. Geuine warmth, too, the music moving as though propelled by summer breezes. Thus the Pan Erwacht moments, when Spring rushes in, bringing change and revitalization, even the hint of wacky, Pan-like disorder. Thielemann brought out the contrast in moods from the elegance of the minueto to the vigour of the scherzo, reinforcing the sense of flow.

Elīna Garanča's voice is a little light for the "O Mensch" gravitas, but her singing was moving, nonetheless and fitted well with the Dresdner style. I had been listening, eyes closed, when the Children's Choir of the Semperoper Dresden began to sing, and suddenly my screen burst into light and shook me - an uncanny but very appropriate moment ! And perhaps most impressive of all, the final movement, which had grandeur and transcendence. Definitely an intelligent and well-thought-through approach to this symphony, and to Mahler. Although we only heard Mahler 3, this performance connected to the deeper ideas in Mahler 2 and 4, and even to Mahler 9 : nature, and triumph, through creativity over struggle.