"Tradition ist nicht die Anbetung der Asche, sondern die Bewahrung und das Weiterreichen des Feuers" - Gustav Mahler

Sunday, 30 September 2018

Saturday, 29 September 2018

15 BILLION views in 6 weeks - The Story of Yanxi Palace

Fifteen BILLION view between 19th July and 1 September, and half a billion on one day alone (August 12th). Phenomenal viewing figures by any standard for The Story of Yanxi Palace (延禧攻略). Viewing figures like that should be major news, since they reflect a mass market untapped by current media marketing models. Yet in the west, barely a mention. Which says plenty about the global market for the arts, and about current west-centric business and political assumptions. It's compulsive viewing. I've watched all 70 episodes (45 minutes each) and want to start all over again to catch more detail. And I don't usually like these kind of sagas and rarely watch TV at all.

The Story of Yanxi Palace is an extravagant historical saga set in the Forbidden City in Beijing during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, a period that out-baroques the baroque and makes even Louis XIV look modest in comparison. It tells the story of a girl who enters imperial service as a maid and works her way up to becoming de facto Empress. A rags to riches story without precedent, particularly cogent since it's based more or less on a true story. Moreover, the heroine, Wei Yinglou (Jinyan Wu), is a ferociously strong personality despite her demure appearance. So much for the idea that Asian women are meek. There always were lots of strong women in Chinese history, despite patriarchal values. Although the Emperor is kingpin in the Forbidden City where no other men can remain at night, the drama predicates around the women in the palace, most of them feisty characters in their own ways, competing to survive. Like the women in the palace, you have to keep alert at all times : the plot moves so fast, with so many sub plots that you're mesmerized. Every episode ends on a cliff hanger.

You're also riveted by the sheer visual richness of the set - elaborate reconstructions of the imperial palace, every inch covered with antiques (or rather very good replicas). Even the slop buckets are cloisonné, and the porcelain in the cha wan (tea cups) is so fine that light shines through them. Best of all the embroidery, created in the workshops that supply the ongoing maintenance needs of the imperial palaces. Please watch part of the making of documentary here Since the plot predicates on embroiderers, this is no minor detail, but a metaphor for dedication, patience and attention to detail. Politics, like embroidery, involves skill. The Qianlong Emperor's father had numerous sons, but chose him to succeed in recognition of his mental discipline and courage. A country the size of China isn't easy to rule. The Emperor's younger brother fools around, "entitled" by privilege”: his weaknesses get him in the end. Yinglou falls in love with Fuca Fuheng, kid brother of the Fuca Empress, the Emperor's first wife, and he with her, but they can't marry. He's aristocratic, she's low level Bannerman family. In any case, duty comes before love. He leads the Emperor's armies in the south and eventually dies in service of the country (while also sacrificing himself to save Yinglou, by then an Imperial Concubine and untouchable). Yinglou's rise to power stems from much the same reason ; not deviousness so much as being more altruistic than the other concubines. She thinks oif oithers than herself, saving the Fuca Empress's portrait from a fire, and sacricing her own health trying to save the Step Empress's son. Always a moral, even in made for TV entertainment. Mental exercise for viewers, too. TV need not be mindless.

The dialogue is in Mandarin, though it's not impossible to follow if you understand Cantonese. Considering that 19% of the world's population lives in China, and that many millions around the world can follow it too, the issue of translation is moot. With an internal market that size, the series doesn't depend on English language audiences. It has been dubbed in Cantonese, Malay, and Indian sub continent languages, but Mandarin speakers say that it's quite literary, so some translations might not convey the full effect. In any case some knowledge of Chinese culture and history does make a difference. Tiny details, for example, like the toddler running round the palace, whose carers can't keep up with him "Fifteenth son !" they call. Just any wilful kid? The Emperor's fifteenth son was Yinglou's child, who would one day become the Jiajing Emperor though they don't tell you that in the story. English subtitles do exist but they're not very helpful. But The Story of Yangzi Palace is such an event in itself that it's sure to be rebroadcast and issued on DVD, presumably with translations and context explained. Hopefully, media marketers, economists and politicians will wake up and smell the coffee. Or rather, the scent of tea.

Thursday, 27 September 2018

Thomas Adès. LPO season opener : Stravinsky Adès Lutosławski

Continuing the London Philharmonic Orchestra's year-long Stravinsky series at the Royal Festival Hall, Thomas Adès conducted Stravinsky's Symphony in Three Movements, Lutosławski Symphony no 3 and his own In Seven Days. Adès has sometimes been a conductor who puts more into his own works, which is perhaps fair enough, but this was a superb Stravinsky - full of vigour, but perhaps even more pointedly, shaped with an understanding of the structure of the piece and how it works as a coherent whole. The Symphony in Three Movements operates like a kaleidoscope, with quotes from other works, notanly the Rite of Spring, appearing, fragmentizing and re-surfacing in new combinations. As has been said many times, it's a bit like the cinematic use of collage, where different frames are put together to create a new whole. Stravinsky would have been well aware of Sergei Eisenstein, so it's perhaps no accident that snippets of music planned for use in the film of Franz Werfel's The Song of Bernadette appear. In musical composition, collage creates impressionistic density, images proliferating in layers and patterns. Stravinsky suggested that some images were inspired by war : hence the brutal, stomping march that evolves from the "primitivism" of the Rite of Spring, ritual now a force for destruction not regrowth. The inner movement is brief respite before savage, angular ostinato figues return. One might, perhaps, read into the piece insights into Stravinsky's predicament, looking back on his past and anxiously ahead, in exile, but the energy of this performance was such that it wholly convinced on its own terms.

This idea of music as collage continued with Adès's own In Seven Days, subtitled "piano concerto with moving image". Ten years ago, when it premiered with Nicholas Hodge and the London Sinfonietta, it was presented with video accompaniment by Adès's partner Tal Rosner, the visuals were given equal billing to the music, to the detriment of the music. Freed of the clumsy caricatures of the video, the piece revealed its true colours. Bouncing, vibrant staccato and twirling traceries of woodwinds suggest freshness and light. Passages where clusters of small, rapid notes evoked stars in the universe, perhaps, or city lights at night – it doesn’t matter either way as both catch the fragmented, flickering mood of the music. A beautiful setting for Kirill Gerstein's rich, deep chords, rumbling at the lower register like some force of nature. The brass and winds behind him provided another texture - long, rising lines - before the tiny fragments Gerstein played, each note cleanly defined and shining. The title In Seven Days refers to the seven days of Creation. Each “day” represents a stage in the formation of the universe, though perhaps it’s best not to be too literal: the impression of a universe being created is what matters. Thus the rushing forces towards the middle section and the moment of mysterious calm which seemed to resonate into infinity. Gerstein's playing in the final section was beautifully assured : no visual images are needed to evoke the sense of some magical dawn materializing in our imaginations. A sudden, unexpected end, hinting at more to come. Visuals better suited to the music might help, but not the originals.

To my eternal regret, I turned down a chance to hear Witold Lutosławski conduct his Symphony no 3 in 1992, but fortunately it is now established canon and performed by other masters. Adès has high standards to meet, but this was very good. For his publishers, the composer wrote "The work consists of two movements, preceded by a short introduction and followed by an epilogue and a coda. It is played without a break. The first movement comprises three episodes, of which the first is the fastest, the second slower and the third is the slowest. The basic tempo remains the same and the differences of speed are realised by the lengthening of the rhythmical units. Each episode is followed by a short, slow intermezzo. It is based on a group of toccata-like themes contrasting with a rather singing one: a series of differentiated tuttis leads to a climax of the whole work. Then comes the last movement, based on a slow singing theme and a sequence of short dramatic recitatives played by the string group. A short and very fast coda ends the piece." But within that such originality !

Startling chords announce its arrival. These form a sharp outline, containing the individual instrumental groups in the orchestra which operate almost in free form between the punctuation points that hold them in. The woodwinds test and tease, strings tiptoe tentatively, celli tracing elliptical figures. As the winds break out of formation, percussion attempts control, but the multiple voices in the orchestra remain irrepressible, even when trumpets scream like klaxons. Zig zag figures, darting forth and flying free. The tension between forms seems to shape the piece as much as the forms themselves. Quieter passages heralded a change of direction : longer, more deliberate liness stretched out, tiny fragments of sound meeting loud chords : a cataclsym where bells and sirens screamed, and timpani thundred. I lovced the way the LPO played the riot (of sorts) that followed, fragments sharp yet sparkling, building up in force. Towards the end an anthem seems to emerge, rising above and beyond. At last, the startling chords are stilled.

Wednesday, 26 September 2018

Birthdays for Infantas and dwarves : Schreker Zemlinsky

Schreker's Die Geburtstag der Infantin was commisioned by Grete and Elsa Wreisenthal, dancers in the "expressive" fashion of the time, an early 20th century rebellion against 19th century ballet. Think Ida Rubenstein and even the character Leni Riefenstahl played in Das blaue Licht rather than Diaghilev and the Ballets Russe. Schreker's original was thus described as "pantomime", and scored for chamber orchestra. The Suite was created for large orchestra, minus dancers and story line. the emphasis now is on the series of dances which work as "pure" music. The last two sections Die Rose and Der Spiegel are missing, for reasons unknown, which is a pity, since these are the punchline of the drama. The Infanta gives the dwarf a white rose : why does it mean so much to the dwarf ? When he sees himself in the mirror and realizes that it is his own reflection he dies of a broken heart.

The idea that music must be "romantic" when there's a big, lush orchestra isn't true. Romanticism with a big "R" refers to the intellectual movement that revolutionized 19th century thought, which impacted on social and political change and on all art forms.romanticism exploreed what we now call the Unconscious, and ideas about psychology before the term was invented. Thus the idea of the mirror, which incidentally exists in Velasquez's painting, where the artist is seen in the background as a reverse image. He's painting the scene yet is also part of the picture. In Velasquez's time, dwarves were no big deal at court, but for Wilde the story predicates on the Infanta who concludes "'For the future let those who come to play with me have no hearts!" So Schreker's suite revision of Die Geburtstag der Infantin should really be understood in context. Far from being slush romance, it has a very dark side, connecting to the taste for morbidity behind the spirit of the period, which found expression in many art forms, from Baudelaire to Wilde, to the Secession in Vienna and Munich, to Hugo von Hofmannstahl, to expressionism in painting and in the cinema. Schreker's Die Geburtstag der Infantin is also not a one-off. Schreker would develop the ideas in many later works, most obviously Die Gezeichneten, where the "dwarf figure", Salvago, creates a paradise which becomes a cover for depravity. What seems beautiful on the surface, just might not be so within. And vice versa - ugliness might conceal true inner beauty. Please read my analysis of the opera here.

And thus to Zemlinsky's Der Zwerg. Significntly, this was written 1919-1921, after Die Gezeichneten, which premiered in 1918, and at a period when Expressionist ideas were influencing art, film, music and literature. The libretto was written by Georg Klaren, adapting the story further, with multiple new connections. Alma Mahler and Franz Werfel (who'd been her partner since 1917) were interested too. The bucolic dwarf in Wilde's story is now a sophisticated composer "from the East", a snide reference to Zemlinsky's ancestry and his father's pretensions to nobility. But Klaren pointed out that the Court, for all its sumptuous riches, was "peopled with over-refined, decadent, not to say tainted characters" while the Dwarf represents a purer soul. There's much more to the opera than Alma, who had dumped Zemlinsky in 1902. By this stage Zemlinsky was successful and married to Luise, a woman almost the reverse image of Alma, and in many ways had sublimated his feelings for Alma in art. As Anthony Beaumont writes, Der Zwerg was like a coffin "to borrow the imagery of Dichterliebe - in which his love and pain were laid to rest". Perhaps the ghosts of the dwarf and those who hurt him are thus buried. Zemlimnsky's next major work was the Lyric Symphony, a masterpiece which breaks new ground musically and in terms of subject. Please read more about that HERE and also HERE

Sunday, 23 September 2018

Autumn comes to Purple Myrtle Garden

For the Mid-Autumn Festival and the full moon tonight, Autumn comes to the Purple Myrtle Garden (紫薇園的秋天) (Tse Mei Yuen Chau Tien) another classic of Cantonese cinema, which was released to coincide with the Festival in 1958. People celebrate with parties, viewing the moon, eating mooncakes, and playing with lanterns. Partly it's the prospect of winter drawing near when light grows dim. But the festival is very much about family values, especially in difficult times. The film depicts the Kok family, who live in a Republic era villa with huge gardens. Hence the name "Purple Myrtle Garden" , lagerstomea, which is beautiful, but fragile. The house is full of books and antiques. The Koks are old money but privilege has come at a price. When the patriarch died suddenly decades before, his widow took over the business, multiplying the fortune. She still rules with an iron fist, controlling the destinies of her children and grandchildren, as well as the money. The matriarch's son is spineless, though good-natured, he and his wife always praying.. (Buddhists). Effectively, the younger generation Koks are trapped in a kind of psychic limbo. Eldest son Kok Chung-si (Ng Chor Fan) plays the violin and paints oils. Eldest daughter Kok Fung-yee (Wong Man-lei) plays the piano. No-one really works. Kok Hok-si (Cheung Wood-yau) goes to the office but "only signs cheques". He and second sister Kok Mok-sau (Yung Siu-yee) go out as often as they can, to escape.

Into this limbo arrives Miss Yiu Ling-yam(Pak Yin) hired to tutor the youngest grandchild, Yik-si, who can't go to school because grandmother says he's poorly. Grandmother decides everything. Miss Yiu notices something's wrong. Family members eat alone in their rooms, and don't communicate. Left to her own devices, she wanders in the garden and overhears the sound of a violin coming from a tower : it's Chung-si playing, all alone. Hok-si and Mok-sau tell Miss Yiu the background. "Purple Myrtle" was their father's first wife, who was driven out of the family by the matriarch. So Chung-si and Fung-yee, left motherless and abused, developed problems. At a gathering, the matriarch (played by veteran star Lai Cheuk-cheuk) comes to visit and bullies each member of the family in turn. "What's this about you attempting suicide?" she screams at Fung Yee. Fung-yee was married briefly but her husband died. "In this family" snarls the matriach, "no-one comes back home whining". (traditionally, women stayed with their married families). That night Fung-yee makes another suicide attempt, but is stopped in time. It turns out that she's still in love with a man the matriach disliked, so she was forced into her tragic marriage).

Into this limbo arrives Miss Yiu Ling-yam(Pak Yin) hired to tutor the youngest grandchild, Yik-si, who can't go to school because grandmother says he's poorly. Grandmother decides everything. Miss Yiu notices something's wrong. Family members eat alone in their rooms, and don't communicate. Left to her own devices, she wanders in the garden and overhears the sound of a violin coming from a tower : it's Chung-si playing, all alone. Hok-si and Mok-sau tell Miss Yiu the background. "Purple Myrtle" was their father's first wife, who was driven out of the family by the matriarch. So Chung-si and Fung-yee, left motherless and abused, developed problems. At a gathering, the matriarch (played by veteran star Lai Cheuk-cheuk) comes to visit and bullies each member of the family in turn. "What's this about you attempting suicide?" she screams at Fung Yee. Fung-yee was married briefly but her husband died. "In this family" snarls the matriach, "no-one comes back home whining". (traditionally, women stayed with their married families). That night Fung-yee makes another suicide attempt, but is stopped in time. It turns out that she's still in love with a man the matriach disliked, so she was forced into her tragic marriage).  When the Mid-Autumn Festival comes, Hok-si and Miss Yiu organize a party in the garden, like normal families do. "Why won't you join us", Miss Yiu asks Chung-si. "it's not me that chooses unhappiness, but sadness which chooses me", he answers. "When you paint", she says, "you can change the colours", ergo, you can change your life. Lanterns are lit, and fireworks. the sound track switches from Elgar and Mendelssohn to a polka and then a waltz and then a jitterbug - Mok-sau's "modern" and likes dancing. (see photo above) In the shadows, Chung-si watches. Shyly, he asks Mis Yiu out, in a ltter. If she wants to go, she should turn on the lamp in her room. She does, and he can't believe his luck. Howeber, he overhears his brother Hok-si ask her out as well. (see photo) So he pretends he can't go, and should instead go with Hok-si who is more fun. Too noble for his own good. Meanwhile, Fung-yee sneaks out at night. Hok-si, Miss Yiu and Mok-sau follow. (Bizarrely the film now shows a street I grew up in, not the country villa used for the other location shoots). Fung yee has gone to find her lost love, Pang Ching-lok, but can't face ringing his doorbell. So Mok-sau alerts him, but Fung-Yee has run away. Hok-si confronts his father, but his father says that the matriarch's will cannot be challenged. "Kok ka pei gui" ie Kok family protocol or values) Mr Pang finds Fung yee and asks her to elope with him, but she's absorbed the family's negative mindset and won't.

When the Mid-Autumn Festival comes, Hok-si and Miss Yiu organize a party in the garden, like normal families do. "Why won't you join us", Miss Yiu asks Chung-si. "it's not me that chooses unhappiness, but sadness which chooses me", he answers. "When you paint", she says, "you can change the colours", ergo, you can change your life. Lanterns are lit, and fireworks. the sound track switches from Elgar and Mendelssohn to a polka and then a waltz and then a jitterbug - Mok-sau's "modern" and likes dancing. (see photo above) In the shadows, Chung-si watches. Shyly, he asks Mis Yiu out, in a ltter. If she wants to go, she should turn on the lamp in her room. She does, and he can't believe his luck. Howeber, he overhears his brother Hok-si ask her out as well. (see photo) So he pretends he can't go, and should instead go with Hok-si who is more fun. Too noble for his own good. Meanwhile, Fung-yee sneaks out at night. Hok-si, Miss Yiu and Mok-sau follow. (Bizarrely the film now shows a street I grew up in, not the country villa used for the other location shoots). Fung yee has gone to find her lost love, Pang Ching-lok, but can't face ringing his doorbell. So Mok-sau alerts him, but Fung-Yee has run away. Hok-si confronts his father, but his father says that the matriarch's will cannot be challenged. "Kok ka pei gui" ie Kok family protocol or values) Mr Pang finds Fung yee and asks her to elope with him, but she's absorbed the family's negative mindset and won't.A thunderstorm descends but cannot drown out the music Fung yee is playing, which resounds tnroughout the mansion. She locks her door so no-one can enter, then climbs on the parapet in yet another suicide attempt. Chung-si climbs over the balconies to hold her back, and she's saved, but he collapses - he has TB. Now at last, Chung-si is decisive : he asks Miss Yiu to marry him. "when I'm well, we can leave Tse Mei Yuen and start a new life." If only. Mr Pang returns from the Philippines and this time, Fung-yee agrees to go with him. But the matriarch's spell is not yet broken. She comes back, orders the servants out and scolds the family. "So you are the Miss Yiu who has changed things here!" "No, says Miss Yiu, daring to answer back "They are changing things for themselves" "Who has let Mr Pang in " the old lady cries. "Me" says Fung-yee's father. "Times have changed". The matriarch forces Fung-yee to read the inscriptions that set out the family protocols from way back. Chung-si speaks out, too and the old lady goes ballistic. "You are a bastard!" As she raises her stick to hit him, his father, at last, intervenes. The spell is broken.

Saturday, 22 September 2018

Debussy Mélodies : Harmonie du soir

Harmonia Mundi continues its comprehensive series of the works of Claude Debussy with this new 2 CD set of Debussy's songs for voice and piano, Harmonie du soir, featuring two pairs of performers, Sophie Karthäuser and Eugene Asti, with Stéphane Degout and Alain Planès. Of the hundred Mélodies which Debussy completed, forty are included here, interspersed like refreshments between courses by individual sections from Images oubliées, which Planès included in his recording of Debussy's complete works for piano earlier this year.

Nuit d'étoiles has received so many glorious performances that they would be hard to eclipse, but Karthäuser and Asti give a good account. In Mandoline, the clarity of Karthäuser's diction and the agility of Asti's, playing makes the song shine. The two books of Fêtes galantes are divided between the two pairs of performers. Degout and Planès are impressive in the second set. A wonderful Les Ingénues, which captures the right tone of sardoniuc sensuality, also expressed in Le Faune, who is a more mysterious entity than mere terracotta statue, and Colloque sentimental, where Degout and Planès shape the pauses so well that the silences speak as pointedly as the text.

Stylish performances, too, of the Trois Mélodies to poems by Paul Verlaine, and Trois chansons de France. These latter are unusual in Debussy's oeuvre, being settings of Charles d'Orléans and the 17th century poet Tristan L'Hermite. Two Rondels frame the central song, setting a mysterious mood. "Le temps a laissié son manteau de vent, de froidure et de pluye" sings Degout. the piano lines trembles, texture upon texture. The central song is La Grotte, where two lovers wander, near a pond where. "l'onde lutte avec les cailloux, et la lumière avecque l'ombre". In this pond, Narcicuss drowned, lost in his reflection. The mini cycle ends with desolation. "Pour que Plaisance est moret, ce May, suis vestu de noir". Written in 1904, these songs reflect something of Pelléas et Mélisande, with their imagery of light and dark, promise and death. As in the opera, the vocal lines rise and fall, the piano rippling hypnotically around the voice. Degout is one of the great Pelléas interpreters of our time, so the excellence of this set should come as no suprise. The Trois chansons de France are followed by Trois ballades de François Villon. (1910). Villon's poetry is more ornate, Debussy's setting respecting cadence and metre, which Degout sings with resonant, passionate richness.

On the second disc, there are five settings of poems by Paul Bourget, completed separately by Debussy at different dates, reflecting the composer's fondness for the poet. Romance (voici que le printemps) is elegant, well suited to Karthäuser's refined timbre, and Les Cloches is built around circular figures defined with charm by Asti. In Beau Soir, the piano line is limpid, caressing the voice, while the lilting melody of Paysage sentimental has charm. Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé present more substantial material for Degout and Planès. The love scene, such as it is, is sinister, filled with foreboding. "Sur l'eau morte ou la fauve agonie des feuilles erre au vent et cresuse un froid villon". In Soupir, the piano part is heavy, almost metallic, Degout singing with haunted gravitas. Together with Placet futile and Éventail, which extend the mood, this cycle is striking, its ambiguous textures unsettling, evoking the aesthetic of the years after the war, and the music thereof, which Debussy would not live to experience. As respite, the softer world of Fleurs des blès and la Belle au bois dormant with Karthäuser and Asti before returning to the darker world of Le promenoir des deux amants, a group of songs to poems by Tristan L'Hermite. This setting of the same text as La Grotte in Trois chansons de France is followed by two songs where the mood is distinctly darker : to use the Pelléas et Mélisande analogy, we're now in the final bedchamber, rather than the castle grounds. Hence the steady, funeral pace and the measured, solemn tones in Degout’s singing. A brief piano interlude (Les soirs illuminés par l'ardour du charbon) while not connected to the songs extends their impact. The collection concludes with Cinq poèmes de Charles Baudelaire presented by Karthäuser and Asti.

Friday, 21 September 2018

So Salzburg pissed her off then ?

Thursday, 20 September 2018

Rattle LSO Barbican - Janáček Szymanowski Sibelius

Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican Hall with Janáček’s Sinfonietta, Sibelius Symphony no 5 and Szymanowkski 's Violin Concerto with Janine Jansen, following on from Sunday’s season opener where Rattle and the LSO did Birtwistle, Holst, Turnage and Benjamin Britten. Please read more about that first concert in my review HERE which was a wonderful experience. As always, with Rattle, intelligent, thoughtful programming. Just as the thread in the first concert was "New Music Britain" linking Holst, Birtwistle, Britten and Turnage, the thread in this second concert might have been "Britain and New Music in Europe". Janáček and Sibelius had huge followings in Britain from very early on, and Szymanowski became a Szymanowski hot spot more than 30 years ago, almost entirely thanks to Rattle's early championship.

Janáček, Szymanowski and Sibelius - three Rattle specilaities upon whom much of his reputation is based.

How I wish that I'd been able to get to both conecrts, since the LSO live broadcast omitted Syzmanowski, which I'd been looking forward to. Rattle, who learned his Szymanowski from Witold Lutoslawski, made Britain a Szymanowski hot spot more than 30 years ago, when the Communists still controlled Poland, and weren't giving the composer the recognition he enjoys today. Rattle's recordings are still the leaders in the field : you need to know them to fully appreciate the composer. So my regret at not hearing Jansen in the Violin Concerto is tempered by knowing there are alternatives. She's done the piece many times, including with Rattle and with the LSO.

Rosa Newmarch, a great musicologist, was aware of Janáček amost before he found his own instinctive voice as a composer late in life, promoting him passionately in Britain,sponsoring his visit to London in 1926. In return, Janáček rededicated the Sinfonietta in her honour. A precedent was established. Only ten years later Vítězslava Kaprálová, aged only 22, was invited to London to conduct her own Military Sinfonietta with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, a work which pays direct homage to Janáček, at a time when Czechoslovakia was being threatened by the Nazi regime. Later Rafael Kubelík was to revive interest in Janáček at the Royal Opera House. Rosa Newmarch was an extraordinarily influential person, working tirelessly for what she cared about and she herself deserves to be given greater acknowkedgement. Please try and get to the Oxford Lieder Festival on 16th October to hear Philip Ross Bullock speak about Newmarch, Janáček and the music of Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia. It's followed by a recital of Janáček's seminally important Diary of One who Disappeared, with Toby Spence and Julius Drake. Please read more here.

The fanfare with which Janáček’s Sinfonietta begins was bracingly bright, the row of trumpeters aligned at the back of the orchestra a blazing sight. Though the piece was initially written to celebrate Czechoslovakia's military, it is as much about freedom and free spirits as about the military. The sharpness of Rattle's attack heralded the transition to woodwind melodies, reminiscent of the pipes in a military band, but also reminscent of the sounds of the countryside. Rattle's approach on this occasion (he's conducted it many times) was vivacious, very open-air. I specially liked the way the fanfare resurfaced, with warmth and vigour rather than brass for the sake of brass. Long string lines floated over resolute foundations, describing the buildings that loom over the city, making a nice contrast with the fourth movement where the trumpets lead a merry march, horns in accord. At last we reach " The Town Hall, Brno" as the last movement is titled. The kings, queens and church no longer reign, though their heritage informs the new Republic. Those cheerfully awry rhythms might suggest the jubilation of the people. The return of the fanfare chorale thus created a sense of unity: past and future linked together with heady optimism.

Britain fell in love with Sibelius very early on. Indeed, the composer's popularity in the west contributed towards international support for the independence of Finland, an example of art influencing life. Again, Rosa Newmarch was in on Sibelius fairly early on. Finlandia was heard twice at the 1906 Proms. Rattle's Sibelius continues a long British tradition forged by Beecham, Boult, Barbirolli, Berglund and others. Most British audiences grow up with Sibelius implanted into their listening DNA, and Rattle has been a part of that. Rattle's Sibelius most certainly is to be reckoned with, not brutalist like Karajan, but more sympathetic to the other forces in the music. Rattle in 2018 with the LSO is of course very different from Rattle with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra twenty years ago, but this was a very good performance. Much of the stylishness of the Berliner Philharmoniker may have rubbed off on Rattle, and the LSO are sounding more inspired and classier than ever. A "warm" Sibelius 5, with grandeur and magnificence, but also human and humane : Sibelius with a soul, so to speak, and all the better for that. Livestream here for 30 days

Wednesday, 19 September 2018

Ian Bostridge Winterreise Wigmore Hall Thomas Adès

Ian Bostridge and Thomas Adès in Schubert Winterreise at the Wigmore Hall. Please read Claire Seymour's review here in Opera Today. Like all good artists, Bostridge doesn't do autopilot but keeps searching for more. Which is the whole point of Winterreise. The protagonist doesn't stop searching, even when he's reduced to following a beggar, or an apparition thereof. Once it was fashionable to assume that the protagonist must go mad and die, because sensible people don't search. Now, thank goodness we realize that there's more to the human psyche than Biedermeyer home comforts. For goodness sake, think about the text !

Will dich im Traum nicht stören,

Wär schad’ um deine Ruh’

Monday, 17 September 2018

Joyous but sharp - Rattle, LSO, New Music Britain

|

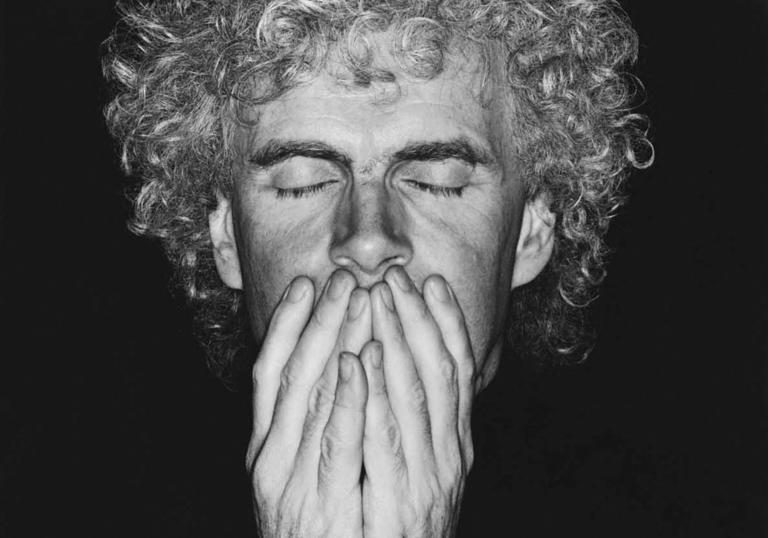

| Sir Simon Rattle, photo; Oliver Helbig, courtesy Askonas Holt |

In a masterstroke of provocative but inspired programing, Rattle followed Birtwistle with Gustav Holst. Holst's Egdon Heath (A homage to Thomas Hardy) op 47 (1927) is rooted in the idea of timeless landscape. Like Hardy's Wessex, Egdon Heath doesn't exist, though it feels as though it should. Low rumbling harmonies, long, ambiguous string lines that seem to be hovering between tonalities: like mist above a heath. Tempi speed up, but clear, long lines return and an anthem-like motif emerges : almost Elgarian in the way that it evokes time and place. A single trumpet rang clear and the sounds dissolved into the ether around them. Though Rattle has built his reputation on new music, he has done a lot of Elgar and Sibelius. This Egdon Heath was a beautifully textured tone poem rich with feeling. Rattle is making connections between Holst and Birttwistle, who creates imaginary landscapes, rough hewn from almost organic forces, merging past, present and future in co-existing layers. Some may scream that Holst isn't "modern" but yes he was, in his own way.

Rattle's gift for intelligent musical juxtapositions is one of his strengths, from which we can learn.

Rattle and Mark-Anthony Turnage have worked together for decades, too. Rattle premiered Turnage's Remembering 'in memoriam Evan Scofield' with the LSO at the Barbican last year (read more here) and with the Berliner Philharmoniker in Berlin. Turnage's Dispelling the Fears from 1994/5 is a much earlier work. Trumpet players Philip Cobb and Gábor Tarkövi are principals of the LSO and the Berliner Philharmoniker respectively, so this performance was also a drawing together of past, present and future. The two trumpets stalk each other in dialogue and at cross-purposes, connecting and disconnecting with the orchestra around them. Though it is a serious work, there's wit in it too, which connected it, in turn, to Benjamin Britten's Spring Symphony.

Britten's Spring Symphony (1948) is big, flamboyant and bursting with good-humoured high jinks - an excellent choice with which to open a new season. Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra were joined here by soloists Alice Coote, Elizabeth Watts and Allan Clayton with the London Symphony Chorus (Simon Halsey), the Tiffin Boy's Choir, the Tiffin Girls' School Choir and the Tiffin Children's Chorus (James Day). The Spring Symphony is more than symphony : it is a piece of music theatre, where visuals count. Here, the youth choruses walked into the Barbican Hall and sang from the edge of the platform, up one aisle and on the stage itself. Not quite as stunning as last year's Berlioz Damnation of Faust when Rattle and the LSO were joined by young singers who seemed to materialize everywhere (Please read more here). But the difference lay in the music itself. Cheerful as the Spring Symphony is, there's something very "English" about it, and its high spirits need a certain degree of discretion. In terms of Britten's output it occupies a strange place. It's not Peter Grimes, but closer to another genre dear to Britten's heart : community music-making for the sheer pleasure of making music together.

Thus the sprawling structure, four parts with twelve distinct sections, which together form a large, impressionistic portrait of Spring in its many manifestations. A Birtwistle "landscape" of sorts If there's any symphonic predecessor, it might be Mahler's Symphony no 3 where summer rushes in with exuberant vigour. Like the god Pan, artists don't follow rules : they create. Thus the many different texts from various sources, some medieval, some modern, and the variety of settings and styles. Wisely, Rattle didn't try to homogenize them, but kept the separate parts distinct, so each shone on its own merits. A blazing "Shine out, fair sun !" set the mood. There are many Brittenesque elements in the piece which would be fun to isolate, and relate to, later works, but it is enough that the work as a whole flows naturally as a series of tableaux. Lively performances : everyone having a good time. whih is as things should be. Rattle, a consummate communicator, knows how to share his enthusiasm with performers and with audiences. A lot of fuss these days is made of grim-faced pious "music education" but this is how things actually work in the real world. Note the final section "London to thee I do present the merry month of May".

Please see my review of Rattle's second concert with the LSO Britain and European New Music - Britain's connections with Janáček, Szymanowski and Sibelius.

Friday, 14 September 2018

Full of promise : Andrè Schuen Schubert Wanderer

The young baritone Andrè Schuen is attracting a lot of interest among Lieder aficionados. A friend who heard him at the Schwarzenberg Schubertiade in August, and at the Wigmore Hall and Oxford Lieder Festival, considers Schuen one of the most promising talents of the last few years. Praise indeed from someone who has been listening for sixty years, and discovered Goerne and Boesch long before most. This new recording, from Avi.music.de, features Schuen and regular pianist Daniel Heide in an all-Schubert programme. Schuen's voice is highly individual, with a beautiful, distinctive timbre that makes him stand out. But there's more to singing than a good instrument. Schuen has an instinctive feel for the way nuance shapes meaning, and innate musicality. In a business where success can come from playing safe and sounding like someone else, Schuen's unique voice and style is something to respect. Though he has yet to mature (he's only 34), Schuen has tremendous potential and promise: if he develops into maturity at this level, he will be a force to reckon with. This Schubert set is a fairly typical collection of favourites, compiled to introduce a new singer to a wider audience, and it is very good indeed as such. But I would also recommend getting Schuen's earlier recording with Heide, with songs by Schumann (Liederkreis op 24), Hugo Wolf and Frank Martin, which is even better and more unusual. Rarely have Frank Martin's 6 Monologs from Jedermann sounded so good. There's also another set of Beethoven songs with the Boulanger Trio. Together these three discs give a fuller impression of Schuen's talents and interests. Please also read here about his Munich recital in November 2017.

The young baritone Andrè Schuen is attracting a lot of interest among Lieder aficionados. A friend who heard him at the Schwarzenberg Schubertiade in August, and at the Wigmore Hall and Oxford Lieder Festival, considers Schuen one of the most promising talents of the last few years. Praise indeed from someone who has been listening for sixty years, and discovered Goerne and Boesch long before most. This new recording, from Avi.music.de, features Schuen and regular pianist Daniel Heide in an all-Schubert programme. Schuen's voice is highly individual, with a beautiful, distinctive timbre that makes him stand out. But there's more to singing than a good instrument. Schuen has an instinctive feel for the way nuance shapes meaning, and innate musicality. In a business where success can come from playing safe and sounding like someone else, Schuen's unique voice and style is something to respect. Though he has yet to mature (he's only 34), Schuen has tremendous potential and promise: if he develops into maturity at this level, he will be a force to reckon with. This Schubert set is a fairly typical collection of favourites, compiled to introduce a new singer to a wider audience, and it is very good indeed as such. But I would also recommend getting Schuen's earlier recording with Heide, with songs by Schumann (Liederkreis op 24), Hugo Wolf and Frank Martin, which is even better and more unusual. Rarely have Frank Martin's 6 Monologs from Jedermann sounded so good. There's also another set of Beethoven songs with the Boulanger Trio. Together these three discs give a fuller impression of Schuen's talents and interests. Please also read here about his Munich recital in November 2017.Wednesday, 12 September 2018

Vaughan Williams A Sea Symphony - Martyn Brabbins BBCSO

The brass fanfare sparkles, strong and bright, rather than brassy, introducing the first line "Behold, the Sea! ". In many ways, this symphony is a secular hymn to the sea and what it might represent, so the voice parts are integral to meaning. For a moment the orchestra sings on its own but the voices rise upon the crest, chorus and orchestra surging forwards together. A roll of timpani, and again the anthem "Behold the Sea!" repeated wave after wave. The tide fades, introducing a new theme highlighted by rhythms that suggest shanty song. Hence the interplay between the first soloist and the chorus, "a chant for the sailors of all nations, Fitful, like a surge". This call and response relationship also suggests sacred song. The flags flying here include a special one "for the soul of man"......a spiritual woven signal for all nations, emblem of man elate above death, Token of all brave captains and all intrepid sailors and mates". Though the influence of Debussy and Ravel is significant, the Sea Symphony is very much part of the English choral tradition, albeit in very sophisticated form. After a brief lull, the music surges forth again, underlined by organ. The baritone returns, singing of the "pennant universal", the chorus and soprano repeating the words in concurrence. Then, as so often in chorale, the first verse returns, the soprano at first on her own, the theme elaborated by the baritone, chorus and orchestra together.

The second movement is introduced by mysterious low harmonies, setting the mood "On the beach at night alone". Here, the organ is particularly resonant, the brass and low timbred winds calling out as if in hymnal. At first the baritone is alone, but gradually joined by small than full chorus. "All nations, all identities......This vast similitude spans them". The voices and orchestra repeat the themes, like waves, rising and falling in volume and force. Beautifully judged orchestral playing, the solo instruments heard clearly, before blending back into the whole, rather like stars in a night sky. The fanfare in the scherzo movement was more tumultuous than the fanfare at the very start, for it describes the churning of waves "in the wake of the sea-ship after she passes" - wild but not "motley" given the precise definition in the music, which Brabbins kept sharply focused.

If A Sea Symphony is a journey. it is one which proceeds, like many journeys, looking backwards at turns, but ever forward. Hence the final movement, titled The Explorers, where the ship appears to be taking off into unknown territory. The scherzo movement operated like a Dies Irae, a monent of judgement clearing the way for a more esoteric future. "After the seas are all cross'd, ........The true son of God shall come singing his songs." The mood is now altogether more esoteric, the first verse serene yet expansive with long lines that seem to stretch and search. Shimmering strings echo the voices of the chorus, then joined by brass and winds, and later organ, repeat the harmonies. After this long choral section, the symphony reaches a new stage. Farnsworth and Llewellyn lead the way ahead "fearlessfor unknown shores on waves of ecstasy to sail". The solo violin defines yet another stage, with an element of peaceful bliss. Thus we are prepared for the section "O thou transcendent". Farnsworth's voice glows, the relative lightness of his baritone well suited to the luminous imagery in the text. In the finale, the energy and exuberance of the first movemen returns, invigorated "Away ! Away O soul! hoist instantly the anchor!" Llewelyn rallies the chorus and the orchestra surges yet again. Sea shanty rhythms are heard again as the "ship" sets forth. The motif "Behold the Sea" is reprised before the very last section, but as the "ship" sails out of sight, silence gradually descends, as if some form of transcendence is achieved. Brabbins's instinct for structure, honed from years of experience in modern music, pays off handsomely in this last movement, which unfolds with great coherence. This A Sea Symphony feels like the herald of a new age, as indeed it was, connecting also to other 20th century music of spiritual yearning.

As a bonus, this recording includes Darest thou now, O soul, a three minute miniature for unison voices and string orchestra, (a hymn with orchestra !) using the same Walt Whitman text which Vaughan Williams used in Towards the Unknown Region. It is an excellent choice, complementing A Sea Symphony not only in terms of poetic ideas but also taking up the violin line near the end of the symphony.

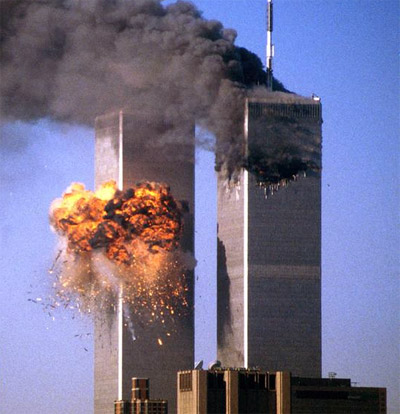

Tuesday, 11 September 2018

9/11 and music

Seventeen years since 9/11 and so much has changed, for the worse. From the wreckage, came messages of love. Instead, hate has seeped into public life, poisoning the system. A moment to reflect on Charles Wuorinen, whose Cyclops 2000 was commissioned by the owners of Cantor Fitzgerald, an unusual alliance between high finance and the avant garde.

The name is a play on Cyclops of ancient myth, who had one giant eye and could only see straight ahead. Hence, it’s written on a single constant metre. The real drama, though, comes from what Cyclops does with his single eye, or rather what Wuorinen does, within the constraints of the metre. The music proceeds in fits and starts, jerking from side to side, switching from rapid tempo to moments of still contemplation. Textures vary : sometimes soloists pulling out from the ensemble, sometimes duetting and exchanging partners in further duets. This gives the piece a strong sense of movement, even though it rises from a simple, single line. The disparate figures are drawn together so the piece moves forward like a quirky, joyous procession, all elements moving in relation to each other, always headed towards a goal.

Read into that what you will. The premiere was in May 2001 in London, conducted by Oliver Knussen, which was recorded. I don't know if it's been done since. On 9/11, Cantor Fitzgerald lost 658 employees outright. No one can count the full cost in terms of bereavement, PTSD, and lives changed for ever. Oliver Knussen is gone, too. The world is not a better place.

Sunday, 9 September 2018

Wigmore Hall Opening Gala - Boesch, Martineau, Heine and friends

To mark the start of the Wigmore Hall's 2018/19 season, Florian Boesch and Malcolm Martineau in a characteristically thought-provoking programme of songs to poems by Heinrich Heine, by Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt and Robert Franz. From Boesch and Martineau, you can always expect the unexpected, but done with intelligence and insight. So I'll start with the end, and the encore, which Boesch introduced as being like those endless but addictive Brazilian TV soaps where relationships go round and round forever. Robert Schumann's Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen, standard repertoire, but rarely heard with such originality. Heine's mischevious wit came to life as Boesch sang, his eyebrows arched in disbelief as he counted the different permutations on his fingers.

"Es ist eine alte Geschichte,

Doch bleibt sie immer neu;

Und wem sie just passieret,

Dem bricht das Herz entzwei".

But back to the beginning of the recital where Boesch and Martineau sang nine songs to poems from Heine's Lyrisches Intermezzo. Had the point of the programe not been evident beforehand, the songs might have come as a shock, since these weren't the familiar texts to Schumann's Dichterliebe but settings by Robert Franz (1815-1892). The two men were contemporaries. Schumann praised Franz's first songs while he was a music critic for Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Hearing Franz's settings of the same texts that Schumann set highlights the difference in their compositional styles. In Franz's Im wunderschönen Monat Mai (op 25/5 1870), the piano part is ornate, suggesting floral imagery, while Schumann's version emphasizes the declaration of love. Schumann responds to the irony in Heine, whereas Franz softens the more sarcastic edges. The strong definition of Schumann's Im Rhein from Dichterliebe (op 48, 1848) suggests the power of the river and cathedral, contrasted with "meines Lenbens Wildnis" : the poet hardly dares speak of lost love. In Franz's version, (op 18/2 1860), "die Augen, die Lippen, de Wanglein" glow radiantly. The suppressed fear in Schumann's Allnächtlich in Taume gives way to sadness in Franz. Schumann represents Romanticism with its sense of individualism and the unconscious, while Franz represents Romanticism in more Beidermeier discretion. Franz, like many other composers of the period, such as Carl Loewe or Franz Lachner, and many others, are important because they remind us of the many different seams in the Romantic imagination

Yet another strand of Romanticism, with an intermezzo before the songs of Franz Liszt, Schumann's Abends im Strand (op 45/3 1840) ; the very image of paintings by Caspar David Friedrich where tiny figures on shore watch ships sailing to unknown places. Ardent figures in the piano part suggest excitement, and the vocal part rises wildly at the phrase "und quaken und schrei'en" before retreating from adventure to the gentility of the last verse where "endlich sprach neimand mehr".

Boesch and Martineau continued with Liszt's Heine settings, including Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam (S309/1 1860), Du bist wie eine Blume (S287 1843-9). In Liszt's Im Rhein, im schönen Strome (S272/1 1840) the piano line depicts the rolling flow of the river, which gradually gives way to more sparkling figures illuminating the last verse which mentions the lost beloved, then ends in reassuring repeated motif. Martineau shone, and Boesch's dignified phrasing added solidity.

The high point in this set was Loreley (S273/2 1856) in one of the finest performances of this song I can remember. Liszt creates textures in the piano part which suggest the sparkling waters, the word "loreley" embedded wordlessly, over and over. The delicacy with which Martineau played showed why this song is so often performed by women. But Boesch has the skills to carry it off even more convincingly. He sang the first verses with tender restraint, creating a sense of wonder : the protagonist is, after all, not the loreley herself but a mortal wondering why the tale is so tragic. He sang the lines "die luft ist kühl" so quietly that a ghostly chill seemed to descend, and even negotiated the tricky sudden ascent to higher range on the word "Abendsonnenschien". Martineau played the second phase of the song to bring out the lyrical, golden warmth with which the loreley seduces. Boesch's voice seemed to glow on the words "Die schönste Jungfrau sitzet" growing with strength and volume, evoking the power of the "wundersame, gewaltige Melodie", leading logically into the next section of the song where the seamen are seized "mit wildem Weh", and hurled to their deaths. Rumbling turmoil in the piano part, Martineau unleashing the fury in the waves, enhancing Boesch's darker timbres as he sang, emphasizing out the menace and horror. This created a wonderful contrast with the last section of the song, where the gentler melody returns, as the river becomes calm once more. Now not only the motif "loreley" repeats but whole phrases, gradually retreating into a serenity which we now know will last only until the next doomed sailor appears.

Boesch and Martineau capped this wonderful Liszt Loreley with an equally impressive Schumann Belsazar (op 57, 1840). They have done this song on numerous occasions, but this performance was exceptional, Boesch relishing the inherent drama but doing it with such naturalness that it didn't feel forced. Theatrical as the scene is, Heine's telling of the story is human. Martineau played the rippling figures evoking the high spirits of the party in the palace, the lines flowing like wine. "Es kirten die Becher, es jauchzten die Knecht" sang Boesch with robust vigour. This matters, for it is drink that makes the King bold enough to curse Jehovah. Boesch's timbre is elegantly regal and his words rang forcefully : "Ich bin der König von Babylon !" Martineau's piano spakled : a last moment of fizz before the mood descends into hushed fearfulness. A sinister chill enetred Boesch's voice, his words measured and carefully modulated, his "t"'s as sharp as knives. Great insight, for that very night Belsazar gets stabbed to death.

After this immensely rewarding first half of the recital came a selection of Schumann's Heine settings, including Die beiden Grenadiere (op 49/1 1840). vividly characterized and muscular, and three Lieder from Myrthen op 25 , Die Lotosblume, Was will die einsame Träne and Du bist wie eine Blume. showing Boesch at his sensitive best. Trägodie (op 64/3 1841) a song in two contrasting parts. Lover elope in hope, but their dreams are doomed. The songs are neither Heine's nor Schumann's finest, so they depend more than usual on good performance. Boesch and Martineau did them so they felt like real people, rather than maudlin figures as in some less accomplished hands I've heard. Boesch and Martinaeu gave a very good account of Liederkreis (op 24 1840) with some extremely interesting high points. Warte, warte wilder Schiffmann suits Boesch's masculine physicality, while Berg' und Burgen schau'n herunter brought out something even harder to achieve ; exquisite, well-defined nuance, for this is an almost bi-polar song and poem. A boat sails merrily on the sunlit river, but above loom mountains and castles, realms of death and night. "Oben Lust, im Busen Tückern, Strom du bist der Liebsten Bild!" In comparison, Mit Myrten und Rosen is full-hearted joy, though it, too, is haunted by a Heine kick in the tail, which Boesch and Martineau brought out with subtlety. Liederkreis can often be the crowning glory of a recital, and this one was good, but the first half of this programme was so unusual and so brilliantly done that this time, for a change, Liederkreis took second place.

Friday, 7 September 2018

Still misunderstood : Britten Paul Bunyan ENO

ENO Studio Live at Wilton's Music Hall for Benjamin Britten Paul Bunyan in a new production. Please read Claire Seymour's review in Opera Today. Nearly 80 years after it was written this opera is still beyond the comprehension of many. Forget the folk story altogether : "From homespun culture manufactured in cities, Save us, animals and men" W H Auden's not being arch. If we don't see "homespun culture manufactured in cities" for the sham it is, we don't deserve anything more than fake and kitsch. It's origins are more Weimar political cabaret, a genre which W H Auden and Christopher Isherwood knew first hand, and which Britten understood. The nearest precedent is Brecht and Weill's Threepenny Opera. Paul Bunyan is not a musical. It is episodic because it depicts a society where attention spans aren't long enough to take on big ideas, or see the bigger picture behind the show. Paul Bunyan is savage, biting satire, a wail of protest against materialism, vulgarity and the desecration of precious ideals. Paul Bunyan doesn't appear in the opera for a very simple reason: he's a myth ! Larger than life, he represents an ideal that can never perhaps be attained. It isn't about America at all, and attempts to present it one-dimensionally trivialize it, creating the very banality it so passionately abhors. The clumsiness of some of the musical writing in Paul Bunyan is in fact artistic licence. Parts of the piece sound corny because what they depict is corniness. Perhaps Britten is demonstrating the truth in Auden's phrase "From the accidental beauty of singalongs, Save Us, animals and men".

Paul Bunyan needs to be understood on its own terms and in the context of Britten's creative development. It connects first and foremost to Our Hunting Fathers, premiered in May 1936, written when Britten was only 23, a work which still suffers from the hysteria unleashed against it in some quarters. Our Hunting Fathers is a work of striking originality. The text for "Hawking for the Partridge" is by Thomas Ravenscroft (1588-1635), Two other texts are anonymous, from the same period, and the rest are W H Auden , one adapted by him from an earlier source. Like Elgar's Sea Pictures, there's nothing specially unusual in mixing texts, as Britten was to do in other works, including The War Requiem. In the case of Our Hunting Fathers, the mock Tudor casing serves as a disguise for intense anguish. Again, Auden's experiences in Weimar Berlin are relevant. He knew only too well what the rise of Hitler meant, and where the conformity of mob rule and militarism could lead. Significantly, the cycle was completed after the Nuremberg Race Laws were promulgated (September 1935). Our Hunting Fathers represents one of the very few early protests against the Nazi regime. Britten's pacifism ran deep, and from a very early age, and went far beyond his connection to Auden. Paul Bunyan, like Our Hunting Fathers is cryptic code. The messages repeat in non-vocal works like the Violin Concerto and Sinfonia da Requiem. And in the less stellar Ballad for Heroes (read more here)

If Paul Bunyan isn't a hymn to kitsch Americana, what is it? In the opening chorus, the singers sing that the Revolution has turned to rain. Management/staff relations in the logging camp are better organized than in many real life businesses. Britten and Auden were well aware of Brechtian dialectics and the political music theatre of their period, and this has some effect on the stylized, almost agit prop narrative. However, Paul Bunyan springs from a much deeper groundswell of pain and disillusion. Britten, Pears and Auden left Europe, hoping to find a new world uncontaminated by the strife of 1930's Europe. Britten's sojourn in America was comfortable, but he picked up on the darker sides of the America Dream. In Paul Bunyan, ancient forests are felled, the wood used for houses and railway tracks. "Progress" moves further west, and with it, conformity, gentrification and hypocrisy. "From patriotism turned to persecution, Save Us, animals and men". Peter Grimes and Billy Budd describe the fate of men who fall foul of bigots and mobs. Britten, Auden and Pears were well aware how J Edgar Hoover was hunting down "subversives". McCarthy's witch hunts would have come as no surprise. Like Peter Grimes, Paul Bunyan and Babe are too big for their boots in a world where pettiness rules.

So, what of the ENO Paul Bunyan ? Please read Claire Seymour's review in Opera Today HERE. As she says, it doesn't appear to deal with the savage irony that is so central to the piece. Maybe the world still isn't ready for grown-up thinking. It took the London media a long time to to get Mark Anthony Turnage's Anna Nicole. Although Paul Bunyan was written for students, I think it either needs students with political nous and passion (no longer a given these days) or a professional cast and team. It's not just the quality of performance that counts but the commitment behind it. One Paul Bunyan that did work was the English Touring Opera production which came to the Linbury in 2014. Please read my review of that HERE.

Tuesday, 4 September 2018

Unsung heroes : Kirill Petrenko Berliner Philharmoniker Proms London

|

| Unsung Heroes : the Berlin Philharmonic on the move (photo: Roger Thomas) |

The same goes for any speculation about what the Petrenko era in Berlin might mean. Just as in any business, chiefs are chosen for what they can do to develop the brand. Karajan made the Berlin Phil tops in the recording industry, Abbado's non-dictatorial style developed them as musicians, and created the panoply of assocuated orchestras. Rattle's gifts as commincator opened up community-oriented outreach. Though it's not unusual for the Berliner Philharmoniker to choose wild cards, as Karajan, Abbado and Rattle were in their time, what matters is to think where the orchestra might be heading in future. Thus the photo above. Who are the unsung heroes who make an orchesatra move? Not just the truck drivers but the organization as a whole, musicians, management and support systems, not just the star at the helm.

Petrenko's two Proms in London exactly replicated recent concerts in Berlin, the first of which was in April, the second on 24th August. (both available on the Digital Concert Hall). The main difference is Yuja Wang's evening gown, a perfectly good reason to enjoy watching. On Saturday I was at Prom 66 for Franz Schmidt's Symphony no 4 in C major, (1933) new to the BBC Proms perhaps but again, hardly unknown. Indeed, Britain is one of the Franz Schmidt hot spots, since his friend, Hans Keller, was extremely influential in British music circles. Schmidt's reputation has been plagued by trying to fit him into pigeonholes. Listen to the interval talk on BBC Radio 3 where Eric Levi and Nigel Simeone, who know what they are talking about, demolish notions about Schmidt's place in music history. If music is good on its own terms it doesn't matter what box it falls into: judging anything by arbitrary assumptions gets in the way of real listening. Schmidt is not Mahler, nor Bruckner, he's himself. That said, Schmidt's Fourth reminds me a bit of Berg's Violin Concerto, not because both were written in memory of a dead woman, but for their chromatic inventiveness.

The long, expansive lines seem to quiver, as if seeking out resolution from unnswerable questions. The lone trumpet sings, plaintively, but with dignity, quiet percussion behind it, like footsteps in a funeral procession. The theme is taken up and developed by solo cello, the strings and winds behind it rising ever upward. The lines are expansively extended, as if the composer didn't want the thread to end, but is cut short by a fast-paced section, which briskly sweeps away what has gone before. Now the instruments rush forth in tight, angular staccato, ending in flaring crescendo. The cor anglais sings a long, mournful line, taken up and expanded by the strings and other winds, on this occasion sounding warm and somewhat serene, Then a last big surge in the orchestra before the trumpet re-appeared, ending with poignant suddeness. Before Schmidt's Fourth, a rather straightfoward account of Paul Dukas's ballet La Péri, which could have been both wackier and lusher, and Prokofiev's Piano Concerto no 3 with Yuja Wang, which was great good fun: a party piece before the funeral.

Petrenko and the Berliner Philharmoniker rested up for the day while Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra did Mahler Symphony no 3 in the afternoon. Please read my review of that HERE. Their Monday Prom, Prom 69, with Shostakovich Symphony no 4 which was even better! Pity it was paired with a lesser work by Bernstein, though well played, with soloist Baiba Skride. It's a pity that the BBC's obsession with tickbox themes has resulted in more Bernstein than anything else, espcially if you include the often uninformed commentary from presenters who seemed to be spouting party line. But back to Petrenko and the Berliner Philharmoniker for Prom 68 with Beethoven Symphony no 7 and Richard Strauss Don Juan on Sunday night. Utterly solid and reliable : an orchestra like the Berlin Philharmonic does not do anything less, ever. Nothing wrong with that per se, but nothing revelatory either. So one does wonder what lies ahead.

Monday, 3 September 2018

Andris Nelsons Mahler 3 Boston Symphony Orchestra Prom London

With Prom 67, Andris Nelsons returned to the Royal Albert Hall, London with part of his old band, the CBSO Chorus and CBSO Youth Chorus, and his current band, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, in a superb performance of Mahler Symphony no 3 in D minor. Like all organizations whose strength is the people within, orchestras need motivation and leadership. The BSO sounds transformed since their last visit to London in 2015 (please read more here), and infinitely more alive than their previous visit eleven years ago. The brass and celli in particular sound rejuvenated. Warming up for this Prom, I'd been listening to the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra where Nelsons is now Chief Conductor, marvelling how the brass there sounds golden and resonant, rarely "brassy". There's a lot of brass in Mahler 3 but it's not a symphony where brassiness or flash exists for its own sake. Nelsons understood why the brass sections matter and how they contribute to the whole symphony in context. In any case, bringing some of the Leipzig glow to any other orchestra is quite an achievement.

This was an excellent Mahler 3 because it was sensitive, respecting the subtitles which Mahler used as a kind of scaffolding as he built the symphony. Notice those titles : "What the Flowers in the Meadow tell me", "What the Animals in the Forest tell me" and "What the Angels tell me". Flowers, animals and angels can't speak: you have to listen on a much deeper level to understand. Thus Mahler withdrew the "scaffolding" so audiences would have to pay proper attention. In a world where muzak values are replacing music values, this is even more pertinent.

The first movement in itself is as long as some entire symphonies, but Nelsons understands the inner structure, which progresses in peaks and planes. Again and again, trumpets lead forward, percussion marking emphatic endings, yet the second theme emerged quietly, heralded by muffled timpani. Very airy-sounding violin and woodwind figures lit the way for the return of the "march" theme, where trombones added darker colours. Yet quieter details mattered, like the hushed diminuendo before the whirlwind of woodwinds, livening the brisk marching pace. Now, sassy, sweeping brass made joyous entry. "Pan awakes", revealing vast panoramas full of promise. The horn call, though, was more restrained, appropriately, for in the mountains, horns are designed to reach over long distances. Thus the solo violin, gentle pizzicato, and harps suggesting perhaps the human world beneath the horizon. A well shaped "wild descent", and a moment to reflect before the next "peak" where percussion and brass interacted : a march though not a funeral march other than in the sense of marking the end of the first stage in this journey. Thus the muted "marching" celli and strings, and the expansive flourish that followed.

After this invigorating first movement, the sweetness and delicacy of the second made complete sense. Again and again in Mahler images of meadows in summer recur as symbols of happiness, won after struggle or remembered during struggle. Mahler was a man who hiked and biked and knew the rhythms. A nice perky start to the third movement, the woodwinds imitating birdsong, a direct quote from the Wunderhorn song Ablösung im Sommer ("Kuckuck ist tod!") . The posthorn, heard from afar, might evoke many things, such as distance, or the inevitable change of time. Yet no lingering, Nelsons keeping the pace exuberant, so the return of the distant posthorn felt suitably poignant, the orchestra an afterglow before the finale, where the brass led a hurtling climax.

This set the mood for the mysterioso movement. "O Mensch, gibt ach !" sang Susan Graham. "What Man tells me", might be an eternal cycle of suffering and rebirth. "Tiefe, tiefe Ewigkeit!". Graham's timbre is lighter than many others, some of whom bring out the Herculean Earth Mother depth in the song, but this works well with this more lively interpretation of the symphony, introducing the glorious highlight of the fifth movement. Excellent interplay between the voices of the City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus and Youth Chorus, and Miss Graham, which reflects to some extent the interplay between brass and percussion in the first movement. The Youth Chorus’s voices were exceptionally fresh, the bimm bamm's ringing with angelic purity.

Whatever the final movement may signify, its long lines stretch into the distance : the strings and brass doing what the post horn did earlier but now present directly within the orchestra. The jaunty march at the beginning of the symphony gives way to what might seem serenity, but may be more complex. Again the brass lead the orchestra into crescendo, suggesting that the march remains, operating as a pulse behind the swathes of orchestral colour. The brass again called forth, percussion crashing : a wonderful moment of near silence from which the solo voice of the violin sang clean and clear. The finale an anthem of confidence, repeating like the march that went before, and ending with emphatic timpani-led tutti.

And here is the finest review I've read anywhere in years ! Marc Bridle, the best in the business ! Please follow THIS LINK