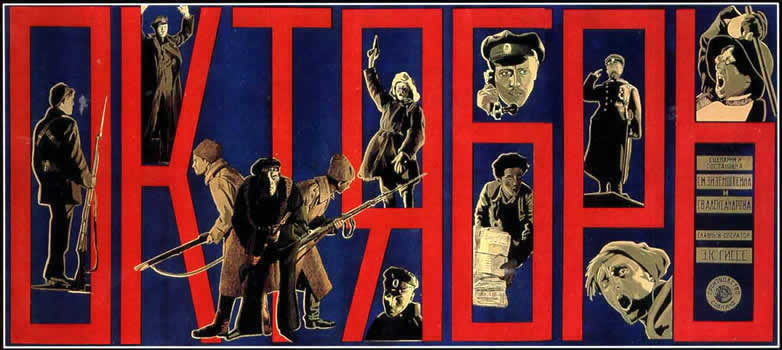

Tonight at the Barbican the London Symphony Orchestra provides live soundtrack for Sergei Eisenstein's silent movie October - Ten Days that Shook the World presented by Kino Klassik in a new edition of the film made in 2012. The LSO will be playing the original music, composed by Edmund Meisel (1894-1930), not the better known music by Dmitri Shostakovich written for the revival of the film for the 50th anniversary of the revolution. This performance is significant because Meisel was an extremely important figure in the very early years of cinema, writing scores for several films, including Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin and Arnold Fanck's The Holy Mountain and other works still being unearthed. Hollywood most certainly didn't dominate early film and music, for early film was decidedly not "Hollywood".

Meisel was connected to experimental film makers like Walter Ruttman who created Lichtspiele, using the medium of film as if it were pliable, like painting, to create abstract works. Think Cubism as movie. See clips of Ruttmann's early work here. Ruttmann's Lichtspiele were Like music! . They were made in co-operation with Hanns Eisler, who wrote music to be played live as the films were screened. So again, the concept of music combined with film before the technology to make sound movies was even possible. Eisler's contribution to music and to film goes much further than agit prop. Yet again, he's a reminder that there's more to cinema than Hollywood, even in Hollywood.

Meisel also wrote the music for Ruttmann's Berlin : Symphony of a Great City one of the most important films of its era, still an icon. Why a symphony of a Great City? Early film makers thought in terms of music, often describing scnes as "acts" as if music drama. Ruttmann's film isn't narrative, but literally a portrait of the city, filmed on the streets, real people, real events, lovingly observed. The raw shots were edited and ordered much in the way that the sounds of an orchestra are put together by a composer writing music. The subject is the city itself, the drama the drama of urban life. Ruttmann employed innovative techniques like odd angles and perspectives, expanding the idea of visual expressiveneess.

Berlin : Symphony of a Great City is more than a movie, it embodies the concepts of modernism in art, film and music. It's not a film in theusual sense of a narrative motion picture. Multiple, diverse images are used like themes in music. They're layered and juxtaposed

like musical ideas. The images are grouped in several main "movements"that as a whole follow a trajectory from morning to night. A snapshot of the life of the city. Please read my analysis of this wonderful work HERE, describing the structure and individual images some of which aren't readily obvious.

Early audiences were often more used to music than movies, and several early films unfold as "movements". The full title of Nosferatu is Nosferatu : eine synfonie des Grauens, "a symphony of horrors". But Berlin : Die Sinfonie der Grossstadt develops the idea on a grand scale. Because it's abstract, much more detail is possible, and thus more possibilties of interpretation Truly "modern" art.

And of Eisenstein's October ? It, too, was innovative, inspired by the new Soviet Union's brief fascination with futurism before Stalinist conservatism froze the tundra of Russian creativity. Kaput to the dreams of the revolution and ideas of new art ! Shostakovich's score is thrilling, but Meisel's connects more to the spirit of the era,

Like Ruttmann, Eisenstein uses film like painting, creating collages and images applied in painterly ways. A statue of the Tsar is seen outlined against the sky. It's torn down by diagonal ropes. A crowd cheers, arms raised heavenwards. Scythes are seen, en masse. Close ups of soldiers faces, grinning, then suddenly, we're in an ornate palace, with elaborate mosaic floor tiles. Cut to angular shots of heavy machinery, to images of starving children dwarfed by huge columns of stone, to shots of a crowd waiting, at night for a train. "Ulyanov ! It's him !"

Diagonals fill the screen, shaking up flat, "natural" order. Flags and banners wave, crowds march, individuals lost in orchestrated movement. Gunshots are fired. Suddenly the tightly packed march disintegrates,figures running wildly across a huge city square. Cannons, horses fallto the ground, crippled. The gates of a huge bridge open, magnificent abstract lines : but a horse is impaled in the machinery; the modern age versus the past, in one horrific image. In a palace, the Provisionalgovernment gathers. Officials walk up and down grand staircases, pre-dating the works of M C Escher. Hurried footsteps, leading nowhere.When the words "For God and country" appear in subtitles, we see, notOrthodox depictions of God but alien Gods - primitive sculptures,Buddhas, Gods so primitive and atavistic that they can't be identified.Tanks arrive to crush the revolution. What we see are rolling tracks, machines of destruction terrifying because they are impersonal. Close ups of guns and individual bullets : the proletariat will fight back.

The bridge across the Neva is raised again, but a ship- with fourimpressive funnels. We see sailors, and cadets marching, as the massive

gates of an imperial palace are pulled shut. A half naked woman cavorts on the billiard table of the Tsar. What's going on ? Through a

collage of images, Eisenstein recreates the tension and uncertainitythat people must have felt in the upheaval. This is cinematic techniqueas art, not unlike the fractured visuals of Cubist painting.

The Bolsheviks mobilize. Eisenstein shows images of hands operating telegraph machines, of armed men rushing up and down staircases, men with bayonets. swathed in smoke. A ravaged looking woman looks up at a marble sculpture : without explicit dialogue, is Eisenstein suggesting the idea of redemption through the high ideals that art can symbolize ? Or something completely different ? Because the nature of art is notnecessarily specific, but the opening up of possibilities. Foir all we know, that's why Stalinists needed conservative "realism" where no-one needs to think.

The army declares for Bolshevism: a forest of bayonets. Wheels are turning, the machine surging ahead. Machine gun clips fire, and

cannons, in such rapid sequence that the images hardly have time toregister. Troops swarm into the palace, ascending the marble

staircases : we can "hear" the sound of their boots in short, sharp images. The Revolution is won ! we see the faces of clocks mark the

moment, in Petrograd, in Moscow, around the world.