| Sakari Oramo, Lisa Batiashvili, Stockholm. (Harrison Parrott) |

Sakari Oramo and the BBC SO continued their current Barbican Sibelius series with Sibelius Symphonies no 4 and 6, with Anders Hillborg's Violin Concerto no 2, with soloist Lisa Batiashvili. Oramo conducted the world premiere last October with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra. These days, major premieres are often planned with numerous performances planned in advance, so the fact that the piece had been done ten times in 13 months means not a lot in itself. But Hillborg's second Violin Concerto is exhilarating : definitely worth the exposure.

The piece begins with a remarkable frenzy of fragmented sounds, dazzling brightly, then retreating into gentle murmur as the violin emerges with long, sensuous lines. The introduction is heard again, in more sophisticated form, when Batiashvili plays a passage where the bow moves swiftly at high pitch. Interesting things too, in the next development, where the orchestra defines percussive figures. Batiashvili played a cadenza that seemed wild but disciplined at the same time. Oddly enough I imagined ancient drummers seated on the earth supporting a dancer : artists from another time and place haunting the formality of a modern concert hall. Then the piece really took off. Traceries and intricate, inventive passions, counterpoint and symmetry : a very rich mix. Swathes of sound from Batiashvili's violin alternated with passages of fast paced virtuosity. Eventually the piece reaches sublimation. The violin sings at top pitch, the lines growing longer and more mysterious. Towards the end the "ancient" rhythms return and the music hurtles forwards with an outburst of energy. The "drums" pound and the violin part swirls like a dervish, lines sliding and twirling. A finale that began suggesting elegy, but suddenly disappeared, like magic.

Oramo's choice of Sibelius's Sixth and Fourth Symphonies added context to Hillborg's second Violin Concerto. After Sibelius's magnificent Symphony no 5, his Symphony no 6 in D minor op 104 (1923) comes as a bracing reparative. hence the famous analogy of fresh spring water as opposed to fancy cocktails. While the vernal quality of Sibelius's Third symphony derives from Nature and the Finnish landscape, the purity of his Sixth Symphony connects to more abstract sources Always acutely aware of what was happening in the rest of Europe, Sibelius reacted by returning to a mode which had little obvious counterpart abroad. In some ways, the Sixth is "about" music, finely distilled and unsullied. Hence the Dorian mode with its suggestions of ancient music, whether Finnish or otherwise, harking back to a kind of primeval consciousness. The orchestration is simple - strings and woodwinds, "allegro" in every sense. Adapting the analogy of fresh water, the music flows freely, elements moving and combining like the passage of a stream bursting from a powerful source. Depth builds up with darker sounds, setting the mood for the figure with which the second movement begins. Purposeful rhythms, contrasts between expansive gestures and primal simplicity. The unusual combination of rolling timpani and woodwinds might also suggest inspiration from sources before modern time. In the final movement, Oramo shaped the "reverential" theme on the strings so it felt like a heartfelt anthem.

And so the programme ended by going backwards, so to speak, to Sibelius Symphony no 4 in A minor op 63, to a point in the composer’s life when he was preoccupied with dark thoughts. Like the Seveth Symphony, the Fourth is shockingly modern in the way it sets out ideas without sugar coating or excess. The themes have a craggy, almost monumental quality ; Oramo sculpted the solidity so firmly that the cello and strings motif seemed to rise like mists. Thunderous timpani, but fleeting, scurrying figures hurried towards the theme heralded by horn calls What do those expansive gestures and the imagery of horns signify ? Are we in a clearing between emotional mountains ? Open textures contrast with tense, repeated moments. There's something feral here as if the music is finding its way like an untamed beast. Hence subdued tones, and searching lines. In the final movement, the "mountains" loom upwards again, but the marking is Allegro. The motif for single violin suggests that small figures will not be crushed. The rushing figures seemed brighter than before, lit by "bells" . Horns and winds together: not alone. The last moments were like an anthem of defiance.

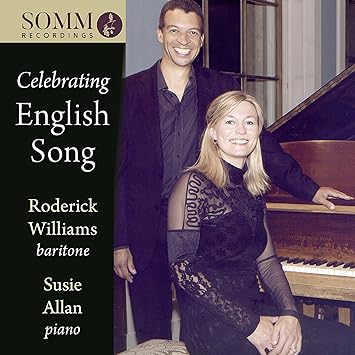

| Hillborg, Batiashvili and Oramo at the premiere of Hillborg's Violin Concerto no 2 (Harrison Parrott) |