On 25th December 1941, Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese. The Japanese had been at war with China on and off for fifty years. For ten years they'd been sweeping through China : battle-hardened troops with a formidable military machine behind them. Manchuria fell, then Shanghai, then Nanjing, then Guangzhou (Canton). British military strategists, to their credit, were realistic. They monitored what was going on, careful to preserve neutrality in the war between China and Japan, though they knew, as Churchill himself was to say, that there was "not the slightest chance " of Hong Kong holding out. Read

Franco David Macri : Clash of Empires in South China (2012, 512pp)

The photo above was taken at the fort at Saiwan, overlooking the Lei U Mun strait, a few days before the first Japanese attack on 8th December (coinciding with Pearl Harbour). It took four days for the Japanese to take the territory, seen in the hinterland. Notice how small the area is. From this position, the men would have been able to watch the battle unfolding across the water and see where bombs were falling in town beyond. For a few days there was an impasse. A small island without resources cannot withstand a siege : no-one, not even the Japanese, wanted another Nanjing. The war changed everything, for China and for Hong Kong : we're still feeling the effects today. Many communities dispersed forever. Hundreds of millions displaced : the biggest refugee crisis in modern times. Millions and millions of individual tragedies. This is just one incident of many, many others, but it is reasonably well documented since it was described in the War Crimes Trials in 1946-7.

In the photo we see the 5th AA unit of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. Notice the chair, for the British officer in command. Like so much else in colonial administration, Volunteer units were organised along racial lines. There were separate units for British and Europeans, for Chinese and for the Macanese community. The 5th AA seems to have comprised a combination of men who for various reasons didn’t fit other categories, so most of these men knew each other socially from before the war. The week before the Japanese invasion began they had been on exercises with the other Volunteers in the New Territories, within sight of Japanese lines across the border.

At midday on Sunday 7th December, the local radio station broadcast the order for mobilisation. The 5th AA had to report for duty by 6pm that evening. Gunner John Litton drove Gunner Algernon Ho in his car. They lived next door to each other in Tytam, near the reservoir. Litton, though only seventeen years older, was in fact Ho’s uncle. Gunner Manuel Ozorio finished a family Sunday lunch, waving to his brother as he left, “Don’t worry, I’ll look after your friends!” His brother, being crippled, was unable to join up with the rest of their crowd, and envied them. Had he been able-bodied, he too would have shared their fate. While the fighting was in progress on the mainland, 5th AA was “shifted around other sectors, 2 days in Stanley, 2 days at Saiwan Fort”. Saiwan Fort was an old Victorian fort, a series of gun emplacements around a main building on high ground. It overlooked Lei Yu Mun Pass, the narrowest stretch of harbour, so close that the men could see across to the mainland with their field glasses. The hill opposite was Devil's Peak, scene of the bitterly fought last Indian stand on the mainland. Then, on the night of 17th/18th December, a Japanese officer (a swimming

champion) swam alone, across the bay, in darkness, to reconnoitre a suitable landfall. across the narrow strip of sea seen above, and the final

onslaught began.

That night, unkniwn to the men in the fort, the Japanese landed in force, crossing the strait on small rafts and logs. They struck land at North Point, not far from where 5th AA were stationed. Late on the afternoon of the 18th, the unit had received artillery fire, which continued without a break until late evening. It was an unusually dark night. Even had there been a moon it would have been obscured by the thick smoke from burning oil installations, and from ships blazing in the harbour. They could see light, from fires, in the direction of the city. Many of the men had homes and families in the vicinity of the fires, but had no way of knowing what was happening in the town. And these were men with no illusions about what had happened in Nanjing and elsewhere. What they felt, as they sheltered from the relentless bombardment in the fort, has not been recorded, but one can speculate. These men still had the optimism of youth, and war might have seemed something of an adventure, for it was so different from their settled, sheltered lives. Brought up in a world where people still had faith in the British Empire, they may even have believed that somehow the Empire would come to their aid, perhaps in the form of reinforcements from China. A Goumindang Army division was in the vicinity, but even if they'd have saved Hong Kong, the political implications were controversial, to say nothing of the logistics.

At 2200 hours they heard shots from close quarters. This was the first indication some of them had that the Japanese had landed. Suddenly, a hand grenade was thrown in from the door, wounding two men. Some were able to escape at this point, including Sergeant David Bosanquet, who was later able to escape Hong Kong altogether and go into Free China. Shortly afterwards, they heard some voices shouting “Surrender, Save you” in broken English. “Sergeant” George Bennett told his men to fix their bayonets and try to force their way out. Several men did get out, but three were killed on the spot. The men then went back into the tunnel below the main gun site where they had been positioned and shouted that they would surrender, and the Japanese told them to come out. Of the 40-odd men, and, intriguingly, some women, possibly servants (for this was Hong Kong where life without domestic staff was unthinkable), who had been in the fort that day, only 29 remained. They came out in single file.

At one stage, one of the survivors saw a Japanese whom he took to be an officer because the man had a long Japanese sword. It made an impression on him, because that was the first time he’d seen a Japanese sword; he would see many in the years to come. The men were then taken to a pillbox several yards away. One of the Japanese took a pack of cigarettes from someone and smoked them while he searched the prisoners. The Japanese had torches, but didn’t use them. Perhaps the light from the cigarettes was sufficient in that small and very crowded pillbox. Fountain pens, watches, even belts were stolen. Only a few of the Japanese took part in the search. Afterwards, they sat smoking while the others guarded their prisoners with fixed bayonets. Two or three hours passed. It was well after midnight when the men heard a shout.

Gunner Chan Yan Kwong, one of the survivors, describes what happened next. “

A semi circle was formed by the guards obstructing the doorway. A loud voice in English was then heard saying that we were free and could leave the pillbox, one by one. However, we were all bayoneted… the bayonet just scratched my abdomen from left to right and the point came out from my clothes, struck my wrist, causing great bleeding”.No more than seven Japanese were involved in the actual bayoneting, though Chan sensed that there were others watching nearby. Gunner Martin Tso Him Chi was perhaps the fifteenth man to come out. Only then did he realise what had happened to the men who had gone before him. Bayoneted across the abdomen from his stomach to his chest, he lay pretending to be dead. He said he thought the sentries were by then tired so they were not as thorough as they might have been earlier. He could see in the light from a fire from a burning ship in the bay the bodies of his comrades: Gunner Kwok Wing Chueng, Gunner Poon Kwong Kuen, Gunner Algernon Ho, Bombardier T N Lau and Gunner Tsang Kai Pan. He saw the last man to be killed, Ting Ping Kwan, try to avoid being bayoneted by pushing up his arms and legs, but Ting died, too.

Then the Japanese came up and battered the bodies with rifle butts and threw them into a pit near what had been their kitchen. Tso, who had been covered by his comrades’ bodies, managed to roll down the slight slope so he fell against the kitchen wall. Tso and Chan lay, separately, among the bodies, listening to the sound of dying men “crying out for God, mother and water” as Chan described, but they thought that the guards were still around. Chan thought he saw soldiers stationed on the horizon. Only later he discovered that they were straw effigies. Gradually the groaning stopped. Tso said that he managed to survive by crawling out to get water and picking biscuits from the ground. He moved a corpse to cover himself when he got back to position, since he didn’t know where the Japanese might be. After several days Chan heard the sounds of looters coming to comb the battlefield, so he crawled to the dugout, hid and removed his uniform. As he was about to leave, he heard a sound from the pit and whispered “Is there anybody alive?” Only Tso answered.

Tso and Chan made their way home. Chan lived in Shaukiwan, not far from the site of the massacre. Tso lived in Causeway Bay a few miles farther on, but on the way home he met a party of Japanese and was forced to do coolie work. The next day, in pain and weak, he made his way to a Catholic church in Shaukiwan where Reverend Father Shek dressed his wounds and looked after him.

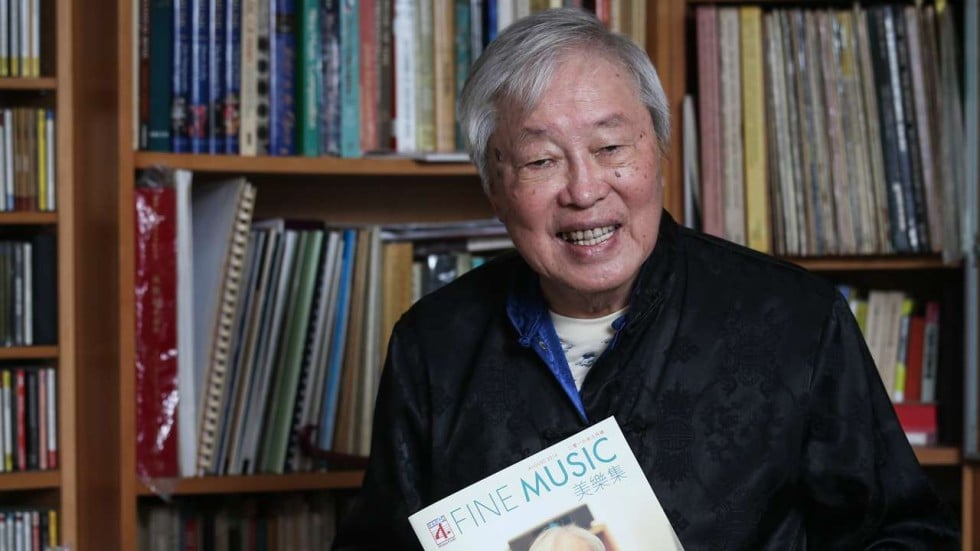

Studying a list of the men who were killed at Saiwan sheds light on the community they came from. The survivors, Tso and Chan, had studied at Diocesan Boys School, an old Hong Kong institution, together with many of the men who were killed – the bodies they saw were not strangers but men they’d known since childhood, with whom they’d played cricket and football. Tso escaped into Free China and became a banker in Guangzhou after the war. In this second photo, see him in his nice western suit. But he's standing by the pillbox where the massacre took place. He's not posing : it's an official photograph taken by the investigators ofvthe War Crimes Commission. After the trial, Tso took the relatives of some of the men who had been killed back to the site for private mourning. This was an act of courage and kindness on his part, as it was the first time he had been back, alone. One of those relatives, Eric Peter Ho, brother of Algernon Ho and nephew of Henry Litton, told me years later how Tso was so overcome by emotion that he could hardly proceed. Tso died young, but left a very talented son who later won a scholarship to study in the US.

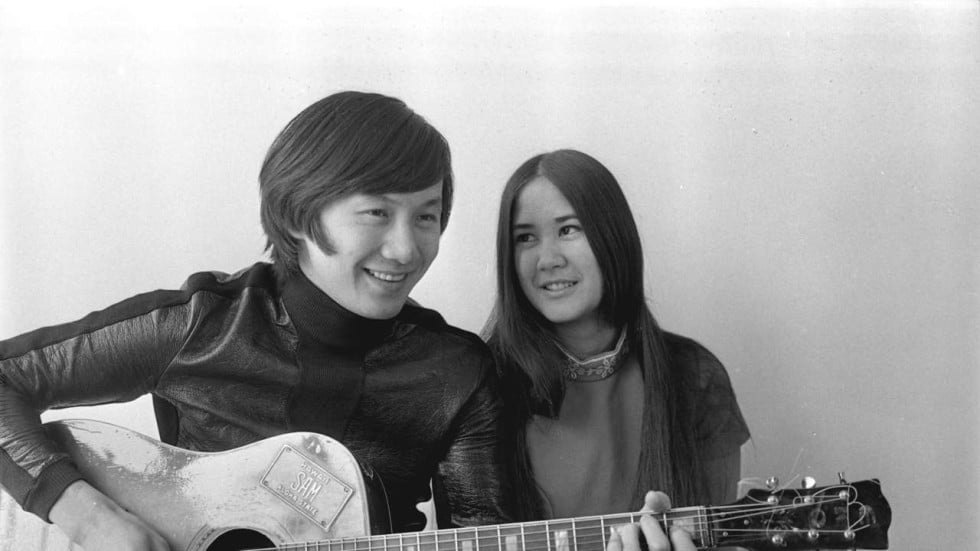

A few of the other men, remembered : Debonair Ernest Fincher had been famous for cricket and swimming parties. Algernon Ho, known to his intimates as “Algy” had that summer graduated from university, and was working as an accountancy trainee at Wong, Tan & Co, the only firm of Chinese chartered accountants in Hong Kong at the time. Litton, Ho, William Edward Broadbridge and Andrew Zimmern (all related) were members of prominent and talented Eurasian families who played an important part in Hong Kong affairs. Peter Ulrich, (third photo) a charismatic and athletic German Eurasian, had been the outstanding pupil of his graduating year, winning academic honours for La Salle, a new, but innovative, Jesuit school. He had in fact started teaching there. He was such an exceptional character that people were talking about him in awe for decades. After the war, his parents were living in Bangkok. Ozorio and Francis Oswald Reed were Macanese who’d grown up in Kowloon Docks, occupied by the Japanese, and later carpet bombed by the Americans in 1944-5, so flattened that you could stand at the shore and look through to the horizon on the other side. Only one of the large Reed family would survive the war. Gunner A Bakar was probably of mixed Chinese and Indian ancestry, his family long-term Hong Kong residents. Chan Yan Kwong, who was 20 at the time of the massacre, went on to become a merchant after the war and remained in Hong Kong. The scars from his wound remained for the rest of his life. He displayed them in court when he gave evidence in the war crimes trials after the war.

Ernest Paterson, whose mother was Spanish, was an undergraduate at Ricci Hall, Hong Kong University. His face smiles out at us from a photograph of the University Science Club, taken a few weeks before. On one side next to Ernie is my Dad, aged 20. They were best friends. My Dad had been crippled in his teens, which is why he could not be a Volunteer like his brother and friends, but ironically that saved his life. On the other side of my dad is Stanley Ho, who would later become the billionaire gambling tycoon of Macau ! and behind them is Oswald Cheung, later SOE, the first Chinese Queen's Counsel, and Member of the Legislative and Executive Councils. Of the whole group only Stanley Ho is still alive. This fourth photo comes from

David Matthews and Oswald Cheung : Dispersal and Renewal : Hong Kong University During the War Years, 1998, 508pp)

Cheung Wing Yee, Poon, Litton, Reed, George Donald Stokes, Tsang and Joseph Nelson Wilkinson left wives and young children. The only man truly alone was Edgar Wallace Bannister, who had long left his parents, far away in England. With these men died a microcosm of the pre-war Hong Kong world they’d known. These men were among Hong Kong’s best and brightest, the hope of their communities, and, in one dark, moonless night they were destroyed.

Those who carried out the massacre were never identified. They weren't officers, and it wasn't a premeditated crime but basic thuggery. In the confusion of the battlefield, it was impossible to tell for certain which unit was where at the time. More than twenty years ago, I decided to find out for myself what had happened, and uncovered the war crimes file in the National Archives at Kew. In the file, there was an envelope, sealed since 1947. But the story was more or less public domain, since it had been reported in the newspapers, Trying to open the envelope, I inadvertently tore it, since it was securely bound into the file. No one had opened the envelope, or set eyes on the photograph, for nearly sixty years. I felt most truly humbled, but it genuinely felt like someone was willing me to be the person to lay eyes on the documents after so many years.

List of men in 5th AA battery listed as killed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Sgt 3834 Edgar Wallace Bannister, 28

Gnr 4571 A Bakar

Gnr 2235 William Edward Broadbridge, 34

Gnr 4134 Chan U Chan

Gnr 4840 Cheung Wing Yee

Bdr 4225 Ernest Francis Fincher

Gnr 4239 Algernon Ho, 21

Gnr 4317 Kwok Wing Chung,

Gnr 4186 Leung Fook Wing, 26

Gnr DR/53 John Letablere Litton, 38

L Bdr 4505 Lau Hsin Nin

Gnr 4198 Manuel Heliodoro Ozorio, 24

Gnr 4861 Ernest Manuel Paterson, 18

Gnr 4188 Poon Kwong Kuen,

Gnr 2798 Francis Oswald Reed, 28

Gnr 4798 George Donald Stokes, 31

Gnr DR/9 William E. Stone

Gnr 4189 Tsang Ka Pen

Gnr 4614 Albert Ulrich, 24

Gnr DR/72 Peter H. A. Ulrich, 25

Gnr DR/31 Joseph Nelson Wilkinson

L Bdr 4268 Andrew Zimmern

Altogether it is believed that about 28 men were killed in this incident, including several men from 7th AA Battery, Royal Artillery, who were temporarily assigned to the unit.

L Bdr George Bennett, 26

Sgt Reginald Edmund Coughlan

L Bdr Kenneth Henry Macdonald

Gnr William Rhoden

Gnr George Robert Ward