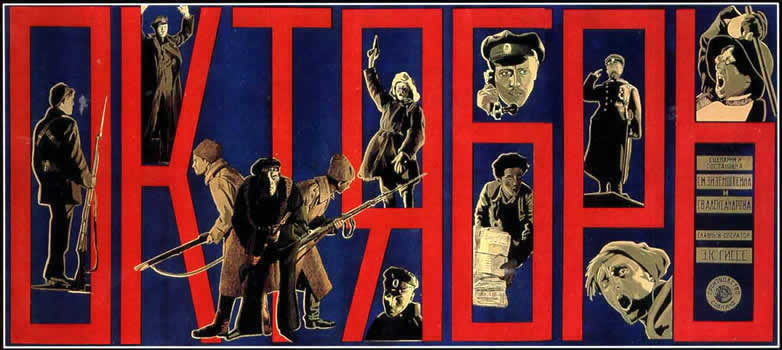

Sergei Prokofiev's Cantata for the Twentieth Anniversary of the October Revolution, Op 74, with Valery Gergiev conducting the Mariinsky Orchestra and Chorus. One Day That Shook the World to borrow the subtitle from Sergei Eisenstein's epic film October : Ten Days that Shook the World. Prokofiev's Cantata was dynamite in many ways. It's an explosion of sound so overwhelming that it needs to be detonated in a performance space as vast as the Royal Albert Hall for full effect. It was also dynamite because it was modern in musical terms, while purporting to celebrate increasingly regressive Soviet values. For a while, the Revolution espoused progressive ideas like futurism and modern art, Eisenstein was probably able to get away with radical innovation ten years after 1917. Twenty years later, Prokofiev was not so lucky. His Cantata was suppressed until Prokofiev and his nemesis Josef Stalin had died, ironically within days of one another. Now, a hundred years after the Revolution, we can perhaps assess its impact on Russia and the world. And with Gergiev and the Mariinsky Orchestra and Choir, we probably had the best possible interpreters.

Eisenstein's film, made ten years after the Russian Revolution of 1917, depicted ten critical days in the struggle, starting with the return of Lenin, culminating with the creation of a new Soviet government dedicated to ideals of peace and equality. Prokofiev's Cantata unfolds in ten sections, highlighting themes in the revolution, some with explicit texts, others in more cryptic orchestral form. Prokofiev prefaced the Prelude with a quote from Marx and Engels A Communist Manifesto, "A Spectre is haunting Europe, the Spectre of Communism". Marx and Engels, though, were writing in 1848 when communism was no more than theory. Prokofiev, on the other hand, had personal experience of what a communist revolution could mean. One wonders if he's praising the system or hinting at something darker.

In the second section, the choirs intone "Philosophers have simply explained the world in different ways. The point is to change it". Another equivocal statement that can be read in different ways. Perhaps the setting hides a clue to meaning. Male and female chorus members sing lines that overlap one another, propelled by strict rhythm like the pounding of machinery. Rising anthems in the orchestra suggest patriotic pride, but they're cut apart by an Interlude with jagged angles, and ominous crashing percussion. Perhaps we're in some huge, infernal machine. In the section titled "Marching in Closed Rank", the voices in jerky lockstep, the rhythms are even more pronounced, highlighted with crashing cymbals and brass. The text quotes Lenin,"...we are singling ourselves out as a special group who have chosen the path of struggle, not the path of compromise".

Yet Prokofiev follows this with a tiny Interlude of haunting quietness before the voices return, the women apart from the men. The revolution has started but its outcome is by no means certain. Thus rushing, frantic figures, passages where the singing is so fast that, with less articulate voice, the line might collapse. Psychologically true: Trumpets call, metallic bells are beaten. We even hear the hint of ships' bells underlining the reference to "Kronstadt, Vyborg , Revel" (where the Navy mutinied). We even hear the wail of a klaxon - a touch of Edgard Varèse? Though it's probably a natural response to the images of machinery and violence. The suggestion of gunfire hangs heavily over the orchestra.

Victory, at last? The women's voices sing a serene hymn, whose sweeping lines mihght evoke traditional hymns of harvest. The men's voices join in. ""The machinery of oppression has been toppled". Yet still Prokofiev paints mechanical processes into his music - the regular tread of machines and processes, the singers clapping their hands in joyless rhythm, the percussion section stamping their feet. A single voice rises from within the closed ranks of the men's choir. "We need the measured tread of the iron battalions of the proletariat". The combined choirs sing a secular hymn of unquestioning obedience to Lenin and his values. The words quote Stalin, whose loyalty to Lenin might not have been as pure as the text suggests.

A section marked "Symphony" follows - flying figures, trumpets and flutes leading forward, the suggestion of pipes and drums, then a semi-pastoral melody, the strings singing as if they were describing fields of corn and a bumper harvest. But grim ostinato intrudes: the timpani growl and the orchestra flies off again in frantic tension. Perhaps in this extended section, with its sophisticated textures and inventive contrasts, Prokofiev is expressing that which cannot be voiced in a totalitarian society. The choirs return, singing in unison, men alternating with women, singing a chorale to words by Stalin, praising the Constitution of the Soviet Union. But in a totalitarian state, constitutional procedures don't guarantee a thing. You could end up in a gulag, as Lina Prokofiev discovered.

So is Prokofiev's Cantata for the Twentieth Anniversary of the October Revolution glorious propaganda? And, if so, for whom and for what purpose? In musical terms it's a lot more sophisticated and subtle than the blatantly crude texts suggest. Was Prokofiev playing a dangerous double game? We may never know, but the Cantata is a lot more than kitsch

Prokofiev's Cantata received its first public performance in 1966. The following year, the Soviet Republic marked its 50th anniversary with a reissue of Eisenstein's October: Ten Days that Shook The World. A new soundtrack was added, specially written by Dimitri Shostakovich. It';s thrilling stuff,. These thoughts absorbed me while listening to Gergiev and the Mariinsky Orchestra perform Dimitri Shostakovich Symphony no 5 in D minor, written at the same time as Prokofiev's Cantata This was a wildfire hit with the regime, rehabilitating him in their good books. Throughout his career, Shostakovich played cat and mouse with the system, not always in the best interests of his music. This performance was so good that Gergiev rehabilitated it for me: it's not usually my favourite., but this was good. Gergiev's also a champion of the music of Galina Ustvolskaya. Initially, she was in Shostakovich's inner circle but eventually their paths turned apart. Ustvolskaya's music was so uncompromising that it compromised her status in society. Who knows what Prokofiev would have made of her? The Prokofiev that might lurk within this Cantata, that is. Keeping Prokofiev and Shostakovich apart, Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 3 in E flat major with soloist Denis Matsuev.