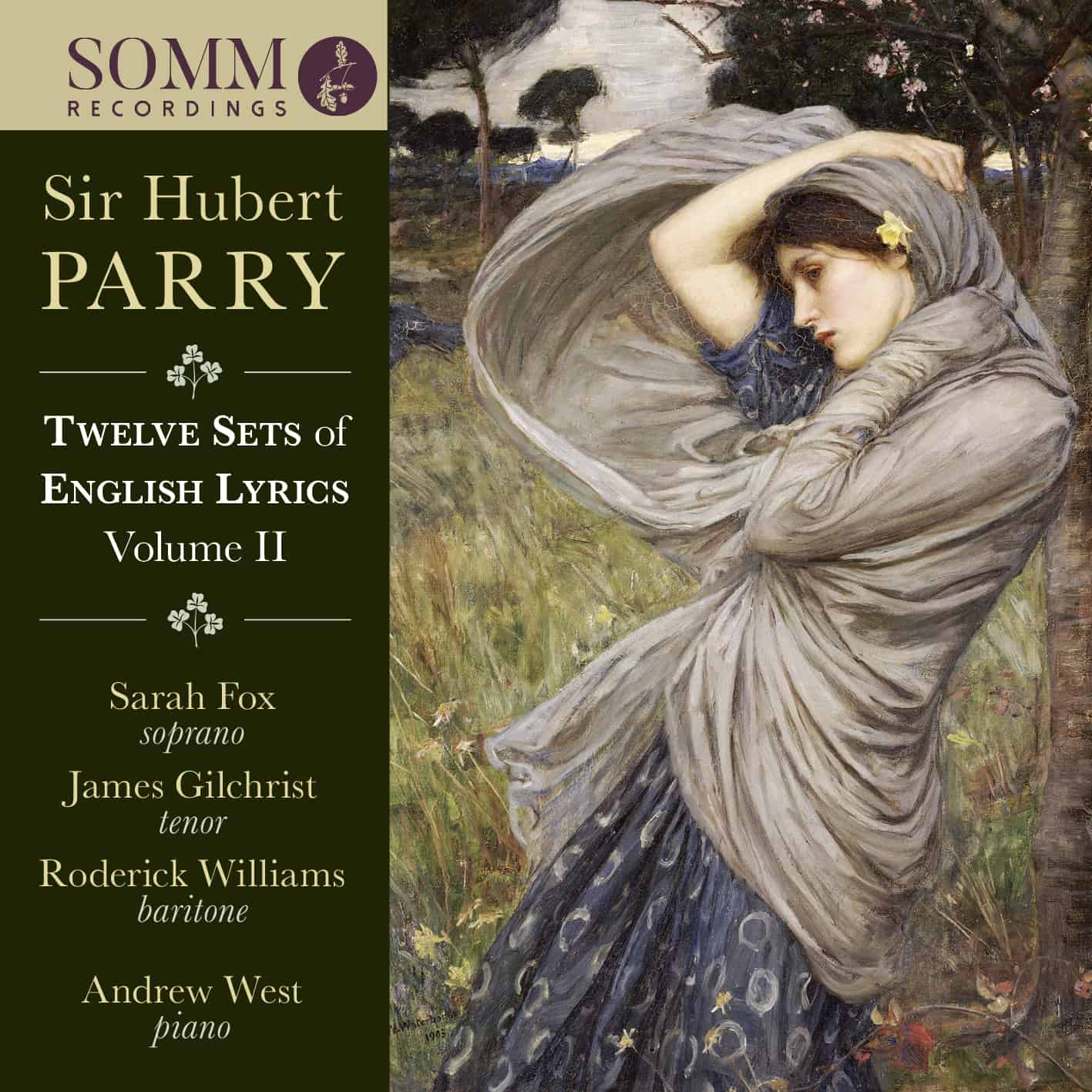

New from SOMM recordings, the second volume from Hubert Parry's English Lyrics. Between 1874 and 1918, Parry wrote 74 songs in twelve collections, all titled "English Lyrics", two sets of which were published after his death. As Jeremy Dibble writes,"The generic title of English Lyrics symbolized more than purely the setting of English poetry (but) also an artistic manifesto and advocacy of the English tongue as a force for musical creativity shaped by the language's inherent accent, syntax, scansion, and assonance". German and French composers were quick to recognize how poetry could develop art song, and even set a great deal of Shakespeare (in translation and adaptation). Parry's interest in English lyrics opened new frontiers for British music. The prosperity of late Victorian and early Edwardian London fuelled the growth of audiences with sophisticated tastes, many of whom travelled and were up to date with music in mainland Europe. The splendid art nouveau interior of the Wigmore Hall attests to this golden age. Until 1914, it was the Bechstein Hall, connected to the Bechstein piano company who supplied pianos - and European music - to audiences beyond the choral society/oratorio market.

New from SOMM recordings, the second volume from Hubert Parry's English Lyrics. Between 1874 and 1918, Parry wrote 74 songs in twelve collections, all titled "English Lyrics", two sets of which were published after his death. As Jeremy Dibble writes,"The generic title of English Lyrics symbolized more than purely the setting of English poetry (but) also an artistic manifesto and advocacy of the English tongue as a force for musical creativity shaped by the language's inherent accent, syntax, scansion, and assonance". German and French composers were quick to recognize how poetry could develop art song, and even set a great deal of Shakespeare (in translation and adaptation). Parry's interest in English lyrics opened new frontiers for British music. The prosperity of late Victorian and early Edwardian London fuelled the growth of audiences with sophisticated tastes, many of whom travelled and were up to date with music in mainland Europe. The splendid art nouveau interior of the Wigmore Hall attests to this golden age. Until 1914, it was the Bechstein Hall, connected to the Bechstein piano company who supplied pianos - and European music - to audiences beyond the choral society/oratorio market.

The first SOMM volume of Parry English Lyrics focused on settings of Shakespeare, Herrick, Beaumont and Fletcher, Sidney et al (Please read more here). In this second volume, the emphasis is on poets of the 19th century, some of whom were "modern", ie contemporaries of Parry himself. A thoughtful choice, for this reinforces the connection to art song in Europe. Parry's setting of Percy Bysshe Shelley's O World, O Life, O Time respects the declamatory nature of the poem, well expresssed by Sarah Fox. There are two settings of Lord Byron When we two were parted and There be none of Beauty's daughters, the latter inspiring a particularly rich piano lovely vocal complemented by a rich piano part, which sets off the crispness in the vocal line, ideal for the distinctive "English tenor" style, highlighting consonants, eliding vowels, sharpening impact. Not all English tenors are "English tenors" but here we can hear how the style connects to syntax and expressiveness. In Bright Star!, a setting of John Keats, James Gilchrist rolls his "r's", and breathes into longer phrases like "or else the swoon of death" shaping each word carefully in the line. Listen to the way he sings "swoon", drawing out the vowel, the sound of which is echoed by the piano, played by Andrew West. In Dream Pedlary, (If there were dreams to sell) to a poem by Thomas Lovell Beddoes, Gilchrist's voice curls around the words, adding magical frisson.

Harry Plunket Greene who was to become Parry's son-in-law, premiered many of Parry's songs for baritone. Perhaps Parry created these songs for Plunket Greene's agile voice and down-to-earth delivery. It's certainly no surprise that Roderick Williams is easily the finest baritone in English song, since he sings with a natural directness which communicates almost as if singer and listener were in conversation, which is ideal for English song, where the floridness of, say, an Italianate style would not work. Also, his voice is not pitched too low, but lends itself to flexiblity and brightness, which suits the English syntax. It's almost impossible to know English song without having heard Williams, whose experience in this field is unequalled. Compare Williams in two songs: Thomas Ford's And yet I love her till I die, an early 17th century air, and Love is a bable, a quasi-folk song. In the first Williams is correct and courtly, in the second, his innate warmth adds sincerity to the wry humour in the song. In Parry's two settings of poems by George Meredith, Marian and Dirge in the Woods, Williams captures the rollicking, open air energy in the songs. In What part of dread Eternity?, to a text which may be Parry's own, Williams's voice darkens forcefully, taking on the solemn tone of the poem.

This recording includes the whole ninth set of Parry's English Lyrics, (1908) settings of seven songs by Mary Coleridge (1861-1907). If the poems are fairly slight, Parry's treatment makes the most of what Jeremy Dibble has called their "lack of ostentation". The songs are simple but dignified homilies. Sarah Fox sings them with lucid purity, reflecting their almost Brahmsian reserve. Elsewhere on this recording, she sings lyrical pieces like Proud Maisie (Walter Scott) and A Welsh Lullaby (John Ceiriog Hughes), a poet popular in 19th century Wales.