No surprise ! Edward Gardner confirmed as Chief at the London Philharmonic, replacing Vladimir Jurowski. Welcome, though not "news", since it was only a question of time before Gardner found a new home in the UK. Gardner has long been the Great Hope of British conducting, often compared to Simon Rattle. He flirts like a star, too. It's part of the job! That's charisma. He's not called "Sexy Ed" for nothing. But all that wouldn't matter, since he is an extremely good conductor and motivator. He's done wonders for the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, who are an excellent orchestra, but he's put them firmly onto the international map. Gardner's career has implications for the British music scene as a whole. His background is solidly British, and he's done a lot of British repertoire, old and new. In fact, the first time I heard him conduct orchestral repertoire, in 2005, he conducted Walton's Symphony no 1, Sibelius and Julian Anderson. Gardner's conducted the LPO before, and the CBSO, and the BBCSO and much else, and has recorded extensively, mainly for Chandos. He was also Music Director at the English National Orchestra for nearly ten years. That, too, is a factor in his appointment because the LPO is the resident orchestra at the Glyndebourne Festival, where they do opera. He was also chief of Glyndebourne on Tour before he joined the ENO. The LPO has done lots of opera unstaged, so he fits the bill.

"Tradition ist nicht die Anbetung der Asche, sondern die Bewahrung und das Weiterreichen des Feuers" - Gustav Mahler

Thursday, 25 July 2019

No surprise ! Edward Gardner to head London Philharmonic Orchestra

No surprise ! Edward Gardner confirmed as Chief at the London Philharmonic, replacing Vladimir Jurowski. Welcome, though not "news", since it was only a question of time before Gardner found a new home in the UK. Gardner has long been the Great Hope of British conducting, often compared to Simon Rattle. He flirts like a star, too. It's part of the job! That's charisma. He's not called "Sexy Ed" for nothing. But all that wouldn't matter, since he is an extremely good conductor and motivator. He's done wonders for the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, who are an excellent orchestra, but he's put them firmly onto the international map. Gardner's career has implications for the British music scene as a whole. His background is solidly British, and he's done a lot of British repertoire, old and new. In fact, the first time I heard him conduct orchestral repertoire, in 2005, he conducted Walton's Symphony no 1, Sibelius and Julian Anderson. Gardner's conducted the LPO before, and the CBSO, and the BBCSO and much else, and has recorded extensively, mainly for Chandos. He was also Music Director at the English National Orchestra for nearly ten years. That, too, is a factor in his appointment because the LPO is the resident orchestra at the Glyndebourne Festival, where they do opera. He was also chief of Glyndebourne on Tour before he joined the ENO. The LPO has done lots of opera unstaged, so he fits the bill.

Thursday, 12 April 2018

Stravinsky Perséphone, Thomas Adès, Barry RFH

Continuing the London Philharmonic Orchestra's Stravinsky Journey at the Royal Festival Hall, Thomas Adès : Powder Her Face suite (new), Stravinsky Perséphone, and Gerald Barry's Organ Concerto. Oddly enough, Stravinsky's Perséphone and Adès's Powder Her Face suite make good bedfellows. Both are unusual works for music theatre that don't fit into easy pigeonholes, both innovative in their own ways.

When Adès's opera Powder Her Face premiered in 1995, its subject caused a sensation. Last revived at the Linbury at the Royal Opera House in 2010, it deserves another outing, not only because it's musically inventive but because it encapsulates a vision of Britishness that still has the power to upset. Scandal, hypocrisy and venality - some things don't change. In the suite, however, we can focus on the inventivenss in the music. This version of the suite is apparently Adès's second. I haven't heard the first but this one's a full-throated (oops) approach which maximizes orchestral drama. Since the characters in the original opera were hard to swallow (oops again), the suite is in many ways Opera ohne Worte and works rather well. Sophisticated London is evoked in the introduction - sharp, brittle figures giving way to sweeping lines which carry such force they sweep all doubts away. A fanfare of sorts emerges - nightclub sleaze but done with stylish flair, a more melancholy melody whipping at the corners which eventually comes to the fore, acompanied by tinkling piano. Circular figures emerge, then the sound of sirens. From silence emerges a sinister theme that coils upon itself in sweeping ellipse. Prickly staccato again - tense and brittle (like the characters in the opera). These battle with the large, looming trombone and tubas. Eventually the orchestra settles into wan detumescence, the woodwinds crying. Suddenly the music flares up - small horns calling, trombones wailing in ferocious fanfare. Towards the end, the "world" retreats, vast figures moving onwards, leaving a violin to sing, almost alone. Frenzied staccato and winds screaming like whips, grunts from the brass. The glamour is gone, but the brutishness remains. Not easy listening but emotionally true.

Stravinsky's Perséphone is part oratorio, part theatre, very much a product of the 1930's with its stylized neo-classical lines. The tenor (Toby Spence) and narrator (Kristin Scott Thomas) operate like chorèges, narrating and speaking for characters, supported by orchestra, and chorus (the Tiffin Boys' Choir). Duality is embedded into the piece, reflecting shifting balances. Perséphone is the daughter of the goddess of fertility, her promise is cut short because she's abducted into the underworld. Thus the ritualized interplay of darkness and light, death and life. I liked the contrast between Spence's austere delivery and Scott Thomas's softer, girlish style. The orchestration is spare : piccolos, cors anglais, and strings (including harp), evoking the instruments of Greek theatre. Contrabassoons moaned, as if in mourning. As Perséphone re-entered the world and Spring returns, textures lightened and the voices of the children's choir rang out brightly.

Between Stravinsky and Adès, Gerry Barry's Organ Concerto. There's no reason why music can't be humorous, but in this case, the joke was on everyone but the composer.

Tuesday, 20 March 2018

Jurowski's Journey : Stravinsky The Fairy's Kiss

|

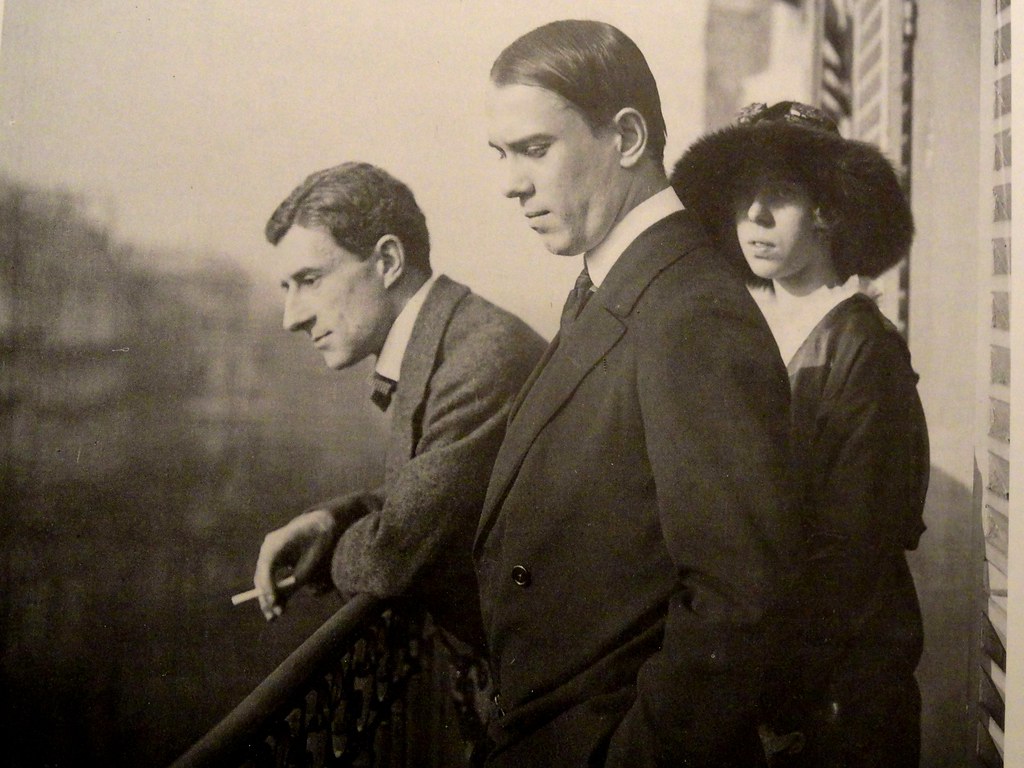

| Bronislava and Vaclav Nijinsky with Maurice Ravel, Paris : Photo: Igor Stravinksy |

Vladmir Jurowski's Stravinsky Journey with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall continued with Stravinsky's The Fairy Kiss, (Le baiser de la fée) framed by Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto no 1 in B flat minor (Daniil Trifonov) and extracts from The Sleeping Beauty. For me, the big draw was The Fairy's Kiss, fashionably maligned in its time, not least thanks to Diaghilev's disdain for Ida Rubenstein, a lovely celebrity but nowhere near the league of the Ballets Russe, and the fact that it was chreographed by Bronislava Nijinsky, who had followed her brother away from Diaghilev circles. Jurowski has a thing for the piece, having programmed and recorded the Divertimento in the past, so I was keen to hear what he would bring to it. Unusually snow bound conditions - for Southern England - might have added vaguely Russian atmosphere, but kept many of us trapped (we had 10 centimters, for the first time in years) but the concert was broadcast on BBC Radio 3. Luckily, weather was fine last night for Ensemble Intercontemporain at the Wigmore Hall - read more here.

Congratulations to Jurowski and the LPO for having the courage to pit Stravinsky's Fairy's Kiss against the ever-popular Tchaikovsky Piano concerto no 1. While Trifonov was reliable, this is a piece which needs more than reliability to reveal itself. Not that most punters care, as long as it sounds familiar, without any special insights. Part of the Fairy's Kiss "problem" is the plot, or lack thereof, but for Stravinsky himself the ballet was "an allegory of a man marked out from his fellows, unable to join in their life" : the role of an artist, whose destiny is to fulfil his gift, even if it means being alone. In 1928, that ideal was pertinent to Stravinky, living in exile, surrounded by change. In Tchaikovsky, he saw a quintessential outsider, forced to hide his true identity in a society where being out meant death. In musical terms, this applied too to Stravinsky, not because he was reverting to Tchaikovsky, but because he didn't want to be constrained by style, or by market forces. It's perhaps ironic that chreographers - Balanchine, Ashton, Macmillan, Ratmansky - have found more in the music than many listeners.

Rustling strings suggested the snowstorm in which the story begins, but typically Stravinskian winds delineated the narrative, leading onwards, then pausing tenderly. Perhaps one might imagine a vulnerable infant who might otherwise die. The pace picked up, winds and brass joining. Lively dotted rhythms, ideal for dancing to, outbursts of bassoon, flute and brass suggested a wild but cheerful procession, the horns adding a "peasant" touch. The baby grows up happily enough in the village, as the music suggests, but on the eve of his marriage the fairy returns, disguised as a gypsy. Tchaikovsky, who entered a mariage blanc may or may not have intuited Hans Christian Anderson's dilemmas about sexuality, but for Stravinsky, this turning point seems ms more artistic than literal. The music abounds with lively figures, ideal for dancing to, offering a choreographer many inentive opportunities. A single violin appears, then a woodwind : two figures, one seductive, once youthful. Eventually, a hush fell over the music, suggesting mystery. Perhaps the boy is enchanted, as the Fairy claims him for her own. Not such a bad fate, for an artist.

Sunday, 9 April 2017

Mahler, Dramatist - Symphony No 8 Jurowski Royal Festival Hall

|

| Curtain call : Vladimir Jurowski, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Festival Hall |

Mahler as dramatist! Mahler Symphony no 8 with Vladimir Jurowski and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall. Now we know why Mahler didn't write opera. His music is inherently theatrical, and his dramas lie not in narrative but in internal metaphysics. The Royal Festival Hall itself played a role, literally, since the singers moved round the performance space, making the music feel particularly fluid and dynamic. This was no ordinary concert. What it lacked in interpretive depth was made up for in being well performed, and more than compensated by the imaginative verve of the semi-staging and the way it highlighted structural ideas in this symphony.

Intriguing questions. Why, for example, preface a two- hour symphony with the ten-minute Thomas Tallis Spem in alium ? The motet is written for forty parts in eight groups of five voices, mirroring the five voice types of the soloists in the symphony. Tallis's text refers to the "Creator caeli et terrae", while Mahler refers to the hymn "Veni, Creator Spiritus" marking the Pentecost, where a divine flame appeared to the faithful, charging them with spreading the gospels to the world. Six hundred years separate the Maurus hymn from Tallis, but in Mahler, the ancient past is re-created for modern times. Thus a sense of primeval continuity, as if an Urlicht were descending upon those who perform and listen to the symphony. Hardly had the singing faded when Jurowski led the orchestra straight into the symphony, without pause. From exquisitely balanced unaccompanied harmonies to the explosive chords of the organ. The "Shock of the New" in every way, for Mahler's Symphony no 8 is unique in so many ways. Thus anointed, we were prepared for Mahler's journey into new territory

This juxtaposition of Tallis and Mahler came perhaps from the concept "Belief and Beyond Belief" the theme of the LPO's year-long series. By no means are all beliefs Christian. While the First Part of the symphony is shaped in the liturgy of the past, the Second Part, despite its references to saints, is secular, based on Goethe's Faust and on a highly unorthodox blend of lust, sin, death and redemption. Gretchen wasn't a virgin, yet Faust is saved by her intervention. Das Ewig-wiebliche, the "Eternal Feminine" for Mahler was entirely personal, and very much as odds with conventional morality.

Thus the logic in this case of inserting an interval between the First and Second Parts of the symphony, which otherwise should be sacrilege. The two Parts of the symphony are meant to be played together without a break, since the slow, quiet beginning of the Second Part acts as an important transition, a kind of "Purgatory" between one plane and another. To split the two parts to make way for a drinks interval is musically inappropriate - Mammon polluting the Temple - the prerogative of philistines. But in this performance, the interval made sense, because it emphasized that the difference between the two parts represents a shift in metaphysics more profound than musical logic. Context is everything, and hopefully audiences will be sophisticated enough to realize that this exception should not become the rule.

The name "Symphony of a Thousand" was not Mahler's idea, but a slogan created by the promoter of the premiere, who realized how the blockbuster aspects of the symphony could be marketed. Because of its sheer theatrical impact, this massive symphony will always be stunning. But as Mahler so explicitly states, the vast forces are bearers of "poetic thoughts", so powerful that they need ambitious expression. It's not spectacle for the sake of spectacle, not a circus for pulling stunts of sheer people management. While volume may be exciting, quantity most certainly is not more important than quality. Both times that I've heard Mahler's Eighth in the Royal Albert Hall, the results weren't convincing since the sound dissipated badly under the cavernous dome.

The Royal Festival Hall seats 2900, so a thousand players would be deafening. Fortunately, Jurowski got around the problem by spreading the singers around the performance space, instead of concentrated in one focal point, deafening audience and orchestra. Sometimes the choirs ranged around the side galleries, where they were heard clearly and to full effect. Wonderful hushed singing, barely above whisper: in a symphony as big as this, that's something special. When the choirs were positioned behind the orchestra, they operated as individual units for the most part until the glorious finale. What a pleasure it was to hear each group distinctly, as opposed to hearing them blended en masse. Much respect for them, singing so well and so clearly, despite rushing about. Incidentally, positioning the choirs in the side galleries resembled the "horseshoe" formation adopted in some early music ensembles The soloists at first appeared in a line between orchestra and choirs. the "sweet spot" in the Royal Festival Hall acoustic. This lessened the strain : no-one forced to shout to be heard.

In the Second Part, the soloists moved positions much more than they do normally. One expects the Mater Gloriosa to sing from on high like an angel, but the other singers moved around, too, especially the women, and Matthew Rose remained surrounded by the orchestra, his deep bass carrying well over the sounds around him. Choirs in motion, singers in motion, but not nearly as distracting as one might fear. The Second Part of this Symphony was inspired by art to which modern perspective did not apply. Thus figures float about disconnected to the landscapes behind them, as oddly as lions behaving like lambs. Similarly, Goethe's Faust depicts unnatural movement - flying through skies, ascension into heaven and so forth. The textures in Mahler's orchestration suggest multiple levels and layers and interesting combinations of instruments and voice. The symphony is constantly in motion.

Throughout Mahler's Symphony no 8, images of light and illumination recur. In this performance, lighting effects (Chahine Yavroyan) were used to emphasize contrasts. Small lights, flickering above the music stands, helping the players follow the page while the hall was in darkness. Large spotlights , highlighting groups of choristers as they sang. The Royal Festival Hall organ, usually hidden behind a screen, was fully open, lit in rich shades of sapphire, alternating gold, and towards the end, silver and iridescence. The organist was James Sherlock.

The presence of microphones in the hall suggested that a recording or broadcast may be available at some stage. All live performances have something extra: this Jurowski/LPO Mahler Symphony no 8 was unique, an experience never to forget.

Soloists were : Judith Howarth, Anne Schwanewilms, Sofia Fomina, Michaela Selinger, Patricia Bardon, Barry Banks, Stephen Gadd and Matthew Rose. Choirs were the London Philharmonic Choir, the London Symphony Chorus, the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge and the Tiffin Boys' Choir.

This review also appears in Opera Today

Please see my 11 other posts on Mahler Symphony no 8 by clicking on the label below