The Leonore Piano Trio continue their traverse through the piano works of Sir Charles Hubert Parry for Hyperion Records with Parry's Piano Trio no 2 and the Piano Quartet in A flat minor. This disc complemeents their first recording, with Parry's Piano Trios nos.1 and 3 and the Partita for piano and violin . (please read more here). The Piano Quartet was completed in January 1879 and premiered soon after at the home of Parry's friend and mentor, Edward Dannreuter. Despite its complexities, it received many performances in the years therafter.. A critic of the time wrote that "It is something to have an English musician who is not afraid to obey the dictates of his inner conciousness, notwithstanding that by doing so he is sacrificing immediate popularity and critical approval". In The Times, Parry's originality drew praise. "Of what special school Parry is a steadfast disciple needs not to be told. He is no timid believer, but a proselyte through intimate persuasion".

"Tradition ist nicht die Anbetung der Asche, sondern die Bewahrung und das Weiterreichen des Feuers" - Gustav Mahler

Friday, 21 June 2019

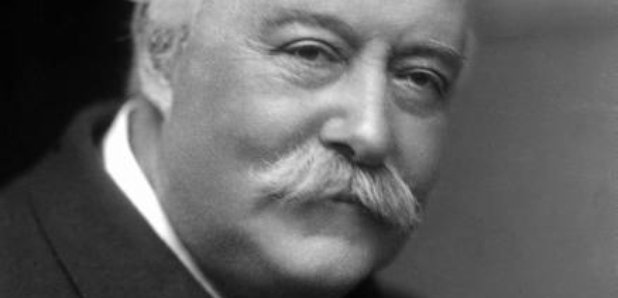

Hubert Parry Piano Quartet and Piano Trio no 2 : Leonore Piano Trio

The Leonore Piano Trio continue their traverse through the piano works of Sir Charles Hubert Parry for Hyperion Records with Parry's Piano Trio no 2 and the Piano Quartet in A flat minor. This disc complemeents their first recording, with Parry's Piano Trios nos.1 and 3 and the Partita for piano and violin . (please read more here). The Piano Quartet was completed in January 1879 and premiered soon after at the home of Parry's friend and mentor, Edward Dannreuter. Despite its complexities, it received many performances in the years therafter.. A critic of the time wrote that "It is something to have an English musician who is not afraid to obey the dictates of his inner conciousness, notwithstanding that by doing so he is sacrificing immediate popularity and critical approval". In The Times, Parry's originality drew praise. "Of what special school Parry is a steadfast disciple needs not to be told. He is no timid believer, but a proselyte through intimate persuasion".

Thursday, 4 April 2019

Impressive Hubert Parry: Judith, William Vann, Royal Festival Hall

Parry's Judith was written for the Birmingham Triennial Festival, vwhich had commissioned Mendelssohn's Elijah, and had also premiered St. Paul. Thus the explicit homage to Mendelssohn in the choruses and perhaps more so in the intensity of conception. Parry achieves this not by the extravagance of late Victorian taste, but with a fairly small orchestra. The detail in Parry's orchestration is so expressive that it needs skilled individual playing. The lines of the vocal soloists are enhanced by soloists in the orchestra. The "Mozart" ethos of the London Mozart Players no doubt contributed to the clarity of this performance. Some very fine playing indeed. Parry also references Bach, using counterpoint to elaborate texture. There are wonderful dramatic effects, too, when needed - oboe and clarinets singing melancholy sweetness, trombones calling like ancient instruments, supplemented by livelier horns. Cymbals and a large tam-tam provide suitably "period" colour.

Very early on, though, Parry's gift for song emerges in Meshullemeth's "Long since in Egypt's plenteous Land", which proved so popular that it was adapted as the hymn "Dear Lord and Father of Mankind" (Repton). Kathryn Rudge sang Meshullemeth, the richness in her voce in keeping with the regal bearing of a queen, though in this case, a queen who isn't a heroine. Sarah Fox sang Judith: Her "Ho! Ye upon the walls! Open to me!" rang out, filling the RFH auditorium with its presence. To sing like this is quite an achievement, especially as she showed no shrillness. Though we don't see Holofernes’ head being cut off, we hear the emotions that brought it about . The brass screamed in alarm, the chorus singing angular lines evoking horror. Toby Spence, singing Manasseh, had many good moments. In the Intermezzo, when Manasseh repents in Babylon, his voice rang with convicts tion "I will bear the indigantion of God" . Later he sang the lovely "Jerusalem is a city", his voice glowing. In this scene, where the Hebrews look towards the camp of the Assyrians, tenor, soprano and the voices of the men in the chorus interact so well that it works as effectively as a scene from an opera. Spence sang Manasseh's "God breaketh the battle" with near heldentenor ring. He must have known how Parry had thought of Parsifal, the fool who learned truth, while writing this oratorio. Henry Waddington sang a very well characterized The High Priest of Moloch and the Messenger of Holofernes, further indication, if any were needed, that Judith is more than oratorio. Excellent performances too from the Crouch End Chorus and from the young singers who sang the King's Children.

Very early on, though, Parry's gift for song emerges in Meshullemeth's "Long since in Egypt's plenteous Land", which proved so popular that it was adapted as the hymn "Dear Lord and Father of Mankind" (Repton). Kathryn Rudge sang Meshullemeth, the richness in her voce in keeping with the regal bearing of a queen, though in this case, a queen who isn't a heroine. Sarah Fox sang Judith: Her "Ho! Ye upon the walls! Open to me!" rang out, filling the RFH auditorium with its presence. To sing like this is quite an achievement, especially as she showed no shrillness. Though we don't see Holofernes’ head being cut off, we hear the emotions that brought it about . The brass screamed in alarm, the chorus singing angular lines evoking horror. Toby Spence, singing Manasseh, had many good moments. In the Intermezzo, when Manasseh repents in Babylon, his voice rang with convicts tion "I will bear the indigantion of God" . Later he sang the lovely "Jerusalem is a city", his voice glowing. In this scene, where the Hebrews look towards the camp of the Assyrians, tenor, soprano and the voices of the men in the chorus interact so well that it works as effectively as a scene from an opera. Spence sang Manasseh's "God breaketh the battle" with near heldentenor ring. He must have known how Parry had thought of Parsifal, the fool who learned truth, while writing this oratorio. Henry Waddington sang a very well characterized The High Priest of Moloch and the Messenger of Holofernes, further indication, if any were needed, that Judith is more than oratorio. Excellent performances too from the Crouch End Chorus and from the young singers who sang the King's Children.As Judith reached its triumphant conclusion, the exuberance of Parry's writing shone forth : wave after wave of excitement, in the chorus and orchestra, cymbals crashing. The lights in the Royal Festival Hall lit up, illuminating the whole auditorium in a way we don't often get to see. A truly theatrical ending to a superb experience. William Vann is recording Parry's Judith for Chandos. Many of those who booked last year when tickets for this perforance went on sale, will be ordering the CD as soon as it's announced. So what if the Royal Festival Hall was woefully under capacity : better to have an audience (apart from the usual freebie crowd) who know what they're listening to! At least we who were there can say we got to Judith on this unforgettable evening.

Photos: Roger Thomas

Please also see some of my other pieces on Hubert Parry, for example

Parry Symphony no 4, Rumon Gamba, BBC NOW, Chandos.

Parry : English Lyrics SOMM vol I

Parry : English Lyrics, SOMM vol 2

Parry : English Lyrics vol 3

Hubert Parry's Jerusalem - more dangerous than you'd think

Parry : The Soul's Ransom

and much more !

Wednesday, 30 January 2019

Hubert Parry chamber works : Hyperion

The Partita in D minor for violin and piano was conceived in early 1877, when Parry was on holiday in Cannes. He was invited to play (as a pianist) in a series of concerts organized by Edward Guerini, an Italian violinist. They performed a suite for violin and piano, based on a piece which Parry had written in 1872-3. In 1886, it was revived as the Partita heard in a recital organized by Edward Dannreuther, who had taught Parry in the 1870's, and was very well connected in European music circles, introducing Parry to new influences.. Dannreuther hosted concerts at this home in 12 Orme Square, Bayswater, featuring the works of Brahms, Saint-Saëns, Greig, Richard Strauss, Tchaikovsky and Dvořák. Dannreuther's son Hubert was named after Parry, who was his co-godfather, the other being no other than Richard Wagner, another close friend, who stayed with the Dannreuthers when he was in London. Edward's other children were suitably christened Sigmund, Tristan, Wolfram and Isolde. Hubert Dannreuther became a naval commander and was one of the few to survive the sinking of HMS Invincible at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, which Parry commemorated in his The Chivalry of the Sea - a Naval Ode. (Please read more HERE) ,

The version of the Partita heard on this recording is the version published in 1890. It bears the influence of French baroque style, flavoured with late 19th century pianism. The first movement, marked maestoso, is a dialogue between violin (Benjamin Nabarro) and piano (Tim Horton), a curtain raiser for the courtly allemande, where the piano provides foundation for a lively violin line. The courante is so vibrant that the music seems to levitate, violin and piano in equilibrium The relative restraint of the sarabande is followed by two bourées fantastique brightened by dotted rhythms and a passepied en rondo.

Dannreuther (later to become Professor of Piano at the Royal College of Music), was pianist for Parry's Piano Trio no 1 in E minor at its first hearing at Orme Square in 1878. Parry handles form with poise, balancing the instruments to great effect. An appassionato leads into an animated scherzo, contrasting with the particularly lovely adagio, where the cello line (Gemma Rosefield) flows gracefully, and the trio comes together again in the allegro giocoso.

Exclusive to this recording is Parry's Piano Trio no 3 in G major, unpublished in his lifetime, edited and prepared for performance by Jeremy Dibble. The opening movement, displays the confidence of a composer who has found his identity, "dominated by an abundance of more extended, self-developing thematic material whose muscular diactonicism is especially characteristic of the composer", as Dibble writes. The lyrical freedom of the capriccio shows equal assurance. Of the lento, Dibble writes, "There is much to remind us here of the inventive, commodious sonata processes which Parry had discovered in so many of his instrumental slow movements, the affecting phrases of the first subject, the composer's passionate use of suspensions, and the typically restive rhythmical momentum of the fluid secondary material". The final movement, marked allegro con fuoco, is unhurried but steady.

Monday, 19 November 2018

Hubert Parry : Twelve English Lyrics vol III SOMM

Because Parry's songs specifically address English art poetry, they mark a departure into new territory which would later be developed by composers like Vaughan Williams and others who sought out folk tradition and by by composers like Finzi, who addressed Tudor, Stuart and Restoration poetry. Notice Parry's term “English Lyrics”, focussing on English as a language. Parry's outlook was progressive, alert to contemporary European influences, which is no demerit, given the extremely high quality of 19th century Austro-German music. Effectively, he was the father of modern British music. Please read more here about Volume I in this series (settings of Shakespeare and 17th and 18th century poets) and about Volume II (where Parry sets poets of the 19th century, close to his own time, not unlike the way that Schubert, Schumann and others set Goethe and Heine.

My heart is like a singing bird dates from 1909, and was written for the soprano Agnes Hamilton Harty, (wife of the pianist Hamilton Harty). The lines fly and soar - like a songbird - and Sarah Fox's clear, lyrical singing does it justice. The text is Christina Rossetti's A Birthday. Extending the imagery, The Blackbird, If I might ride on puissant wing and A Moment of Farewell. The first is relatively straightforward but its very simplicity evokes the folk song adaptations that became popular in the Edwardian period. A Moment of Farewell, (to a poem by John Sturgis) however is more sophisticated with an elaborate, rolling piano line, (pianist Andrew West) evoking the “buoyant emotion” of a “bird flying far to the ocean”. With The Sound of Hidden Music, Parry is writing art song as fine as any German composer’s. The piano introduction flows elegantly, almost caressing Sarah Fox's lines. Although the poem, not specially adept, is by Julia Chatterton, unknown today, Parry's response lifts it well above the ordinary. The memory of “things of life that touch the heart are things we cannot see” warm the spirit in winter. It was signed on his 70th final birthday in 1918, inscribed with the words “Slowly and with deep feeling”. This was to be his last birthday, and final completed song. There is some evidence that he did not think he would live out the year, and indeed, he died some months later.

Just as Schubert set poems by people he knew, Parry chose poems by friends who meant a lot to him, which tells us much of his humane and caring personality. Nine of his seventy-four English Lyrics (eight included in this collection) are settings of John Sturgis, Parry's classmate at Eton and fellow student at Oxford. Like Parry himself, Sturgis was able to switch to art from business. Through the Ivory Gate describes a vision of a dead boyhood companion. “No friendship dies with death”, sings Roderick Williams, whose style of direct communication makes the song feel personal. A Stray Nymph of Dian, another Sturgis setting, describes a Grecian nymph, and draws from Parry a more declamatory approach. A Girl to her Glass is flirtatious, while Looking Backward is not melancholy – not a Parry characteristic – but thoughtful. Grapes is boisterous, as befits a paean to Bacchus. “Grapes, grapes, grapes beyond all measure!” sings Williams with good humour.

Alfred Perceval Graves, an Inspector of Schools, was well known in Victorian times. “I am weaving sweet violets, sweet white violets” sings Williams in A Lover's Garland. Parry's setting is elegant, reflecting the classical reference to “Heliodora's brow”. At the Hour the Long days Ends in lesser hands than Parry's might have veered close to parlour song, but he treats it with dignity. Graves's poem The Spirit of the Spring, with its references to Taunton town and archaic words like “maund” (a unit of weight) is quaint in an artificial way – he was no Housman or Hardy – but Parry, like Schubert, could elevate less than ideal verse with good musical setting.

The rather better poetry of Langdon Elwyn Mitchell inspired Parry to greater heights. Nightfall in Winter captures a sense of enveloping darkness. The piano plays single notes in succession, suggesting the steady coming of night, cold and frost. “The clouds obscure the sky with gloom”, sings Williams, his voice rising upwards for a moment before settling back into somnolent mood. Mitchell also wrote the text for From a City Window, one of Parry's best-known English lyrics. “I hear the feet below”, sings Sarah Fox, as West plays the bustling piano part, “(which) go on errands bitter or sweet whither I cannot know”. A long pause, for rumination before the second verse, “A bird troubles the night” evoking “vague memories of delight”. Another, shorter, pause before the final strophe “And the hurrying, restless feet below, on errands I cannot now, like a great tide ebb and flow”. A strikingly modern song, with its urban context and sense of unknown possibilities, the bird a symbol of longing yet disquiet. Although Parry's Twelve Sets of English Lyrics have been recorded before in various forms, this series from SOMM is a landmark because it presents the complete collection, together with good notes and good performances, establishing Parry's role as the pioneer of modern English song.

Saturday, 17 November 2018

Hubert Parry : Songs of Farewell - Quinney, New College Choir, Oxford

The disc begins with Parry's Hear Ye, O my people ! Written some twenty years before the Songs of Farewell, it is solidly in the “Cathedral” style typified by Samuel Wesley, for massed voices. It was first performed by the Salisbury Diocesan Choral Association which could deploy up to 2000 singers. Initially the organ dominates with spectacular effect, but a solo quartet soon emerges, defining the line and leading the unison voices. A solo aria for bass “Clouds and Darkness” creates further focus. In contrast to the might that has gone before, “Behold, the eye of the Lord” shines with lightness, the purity further underlined by a youthful treble. The organ introduces the hymn “O praise ye the Lord!” drawing together the soloists, the choir and the magnificence of the New College organ (here played by Timothy Wakewell). The influence of Bach is detectable in the structure, showing the depth of Parry's understanding of wider European sacred music.

It's entirely apposite, therefore, to hear Mendelssohn's Sechs Sprüche in this context, given how Mendelssohn acknowledged Bach. Mendelssohn's oratorios and other works were received with such enthusiasm in this country that he is effectively a British composer by adoption. These six motets date from 1843-1846 and were written when Mendelssohn was Generalmusikdirector to the Hohenzollerns in Berlin, and reflect the Prussian pietist aesthetic. The songs are a capella, their beauty unadorned, so to speak, the blending of voices reminiscent of the early Lutheran Church, of Heinrich Schutz and even of Palestrina. Each motet addresses Christian themes – Christmas, New Year, the Ascension, the Passion, Advent and Karfreitag (Good Friday), and are readily adaptable for liturgical use.

Parry's Songs of Farewell can thus be heard in context, their contrapuntal clarity built on firm foundations. Though not entirely secular, they aren't religious in any restrictive sense, but reflect Parry's interest in ethical issues. "My Soul there is a Country", sets a 17th century text by Henry Vaughan. The “country” here isn't a nation in the modern sense, but a place beyond “foolish ranges” where grows “the flower of Peace, the Rose that cannot wither”. “I know my Soul hath Power” places moral responsibility on the individual. “I know myself a Man, which is a proud and yet a wretched thing”. “There is an Old belief” refers to the idea “old friends” shall meet again after death “Beyond the sphere of Time and Sin”. God appears in “At the round Earth's imagin'd corners”, to a text by John Donne, the vocal setting radiant, voices subtly and beautifully parted. “Lord let me know mine End” is poignant, given that by 1918, Parry's health was declining. He didn't live to hear the Songs of Farewell performed as a group at a memorial concert in his honour, at Exeter College Chapel with the combined choirs of New College, Christ Church and the Oxford Bach Choir, under Hugh Allen, Parry's friend and successor at the Royal College of Music.

As a bonus, Parry's Toccata and Fugue for organ in G major and E minor, from 1912, written for an organist who lost his right arm in battle in 1917 but survived. When Hugh Allen performed it at New College a few years later, he played with one arm tied behind his back. In this “intense, elliptical work, writes Robert Quinney in his excellent notes, “the advanced chromaticism and sometimes dense texture is reminiscent of the neo-Bachian form and harmony of Max Reger”. Just as there's a case to be made for Parry as the father of modern British music, he has a place in the wider European mainstream.

Please see my other posts on Hubert Parry, including

Parry Symphony no 4 - Rumon Gamba, BBCSO Chandos

Parry Twelve Sets of English Lyrics from SOMM Vol 1 Vol 2 and Vol 3

Parry Symphony no 5 at the Proms 2017

Parry and the Battle of Jutland

and much more

Monday, 29 October 2018

Superb Hubert Parry Symphony no 4 Rumon Gamba Chandos

From the first bars, Gamba's attack is forceful, emphasizing the strength of the Doric theme. The passage leads to nine other sections, which move swiftly ranging from animato to sweeping largamente, Gamba revealing the tight structure behind the restlessness and constant change in the long development. The brief intermezzo serves as a transition to the third movement marked Lento expressivo with a short interlude between the first and second sections. Jeremy Dibble, who edited this version, describes its "lyrical pathos" thus : "The diatonic richness of the slow movement's first idea is classic Parry in its treatment of dissonance and sonorous string texture, and the falling sequences and double suspensions of its closing bars seem palpably prophetic of Elgar." (who, incidentally was in the audience for the premiere). "And while the light hearted second subject attempts to assert itself, it is the noble generosity and poetry of the first idea that prevails.". Parry may have amended the Scherzo but its freshness and dance themes led him to re-arrange it for piano duet. The Finale is dramatic, working out the tension between dance and march, including "an unexpected and arresting shift to D major at the centre". The strong theme of the first movement returns in the Finale but the movement concludes with confident assurance. Parry would attach titles to the later revision to symbolize stages in search of self discovery. His summary was to be "Finding the Way".

Hearing Parry's Symphony no 4 (1889) with three movements from his Suite Moderne (1886) highlights the composer's progressive ideas. Initially concieved in symphonic form, Parry uses an Idyll, a moderato in C major in place of a more conventional Scherzo. Yet Scherzo it is, a lively jest, hunting horns and dance figures alluding to Arcadia, followed by an even gentler Romanza as slow movement. There's something stylishly "modern" (ie late Victorian) in its expansive self-assurance. Significantly, Parry was supportive of Elgar from a very early stage. These two movements were placed between a Ballade (not included here) and a Rhapsody with three sections in seven and a half minutes, reminiscent of the long development in the first movement of Symphony no 4. This complements Parry's only ballet Proserpine (1912) for orchestra and chorus, based loosely on a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley where maidens gather flowers in a sunlit meadow, unaware that Proserpine will soon be kidnapped and forced into marriage by Pluto, doomed to spend half the year in darkness underground. So much for Arcadian innocence !

Please see my other posts on Hubert Parry and on British music. Please join my Hubert Parry page on FB

Wednesday, 24 October 2018

SOMM Remembrance - Choral music by Ireland Holst Parry Elgar

This Jerusalem is thus positioned between the words from the Bible, and a text associated with the outbreak of the 1914-1918 war. In Greater Love Hath No Man, Johnn Ireland sets the crucial phrase for solo baritone (Gareth Brynmor John), "that we, being dead to sins, should live unto righteousness". Ireland was writing in 1912, before the onset of war, when the sacrifice meant Christian sacrifice. Jesus died for all men (and women) regardless of place and time. For the Fallen, reflects the way the message adapted after the impact of war. The piece was written in 1971 by Dougas Guest (born 1916). Though much of Laurence Binyon's original is belligerent, Guest, who served in the Second World War, sets only one verse, placing emphasis on the sombre, humbling line the words "We shall we remember them".

Sir Edward Elgar's setting of They are at Rest, to a text by John Henry Newman, is an elegy marking the ninth anniversary of the death of Queen Victoria, while O Valiant Hearts by Charles Harris, a friend of Elgar, is a postwar reflection on loss. I Vow to thee, My country is Gustav Holst's adaptation of Jupiter in The Planets as the anthem. Its serenity links earthly death with concepts of eternal life, on another plane. Holst's Ode to Death is heard here transcribed for choir and organ (James Orford), as is Gabriel Fauré's Requiem in D minor arranged by Iain Farrington. Ian Venables's Requiem Aeternum (2017) completes the set, a timely reminder that death is a part of the cycle of life.

Please also see my review of Earth & Sky - choral works by Ralph Vaughan Willaims, also conducted by William Vann, for Albion Records.

Sunday, 7 October 2018

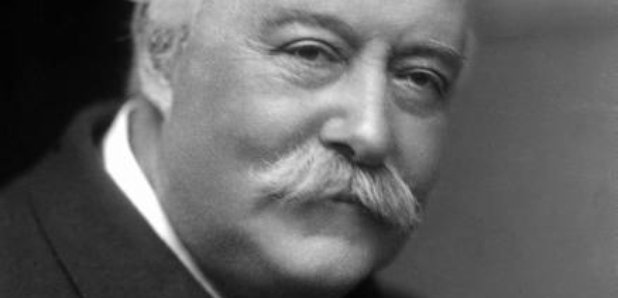

Hubert Parry died 100 years ago today

C Hubert Parry, who died 100 years ago on 7th October, will be Composer of the Week on BBC R3 from Monday. Available online, internationally for 30 days. Events coming up soon

C Hubert Parry, who died 100 years ago on 7th October, will be Composer of the Week on BBC R3 from Monday. Available online, internationally for 30 days. Events coming up soon

All day Parry at the Oxford Lieder Festival on 19th October, with talks (Jeremy Dibble) , two concerts (James Gilchrist) and a chance to visit theParry archive at the Bodleian Library

New CD release : Parry Symphony no 4 original version in new edition by Jeremy Dibble, with Rumon Gamba conducting BBC NOW, on Chandos

Lots on this site about Parry - use the label at right or below. Please visit my Hubrert Parry Group on Facebook

Thursday, 2 August 2018

Hubert Parry : Invocation to Music

A splendid orchestral introduction to Parry's Invocation to Music, long string lines rising to crescendo, seguing into joyful processional. "Myriad voiced Queen ! Enchantress ! of the air!" sing the choir ; magnificent rich textures, voice types clearly defined and separate. "Chained in unborn oblivion drear, thy many-hearted grace restore unto our Isle, our own to be ! And make again our Graces three"...... "Return, return to merry England, return, enchantress, myriad voiced Queen!" The text, by Robert Bridges is somewhat turgid - Parry wasn't terribly keen - but perhaps we can intuit what this Purcell revival meant to the late Victorian age, with its confidence and sense of imperial grandeur. Thus the intertwining of choral parts and orchestra may be designed to form a garland in music.

Parry valued Purcell highly and ensured that his students did, too. But apart from the introduction, Parry's Invocation isn't so much "about" Purcell as about the ethical and moral mores of Parry's time. Delicate woodwinds announce a more contemplative mood for the second section, "Thee, fair poetry" for tenor solo, decorated by murmuring orchestra. Images of the countryside abound, but this landscape is strangely haunted, living in nostalgic memory rather than the present. "Only awhile the distant sun from hidden villages around, threading the glades and woody heights is borne of bells that dong the Sabbath morn" This song is also a memorial to Parry's schoolfriend George Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke, whio died young while the Invocation was being completed. George was also the brother of Parry's wife Maude, but that's another story. Thus the very private tenderness: not at all a grand public statement, despite being embedded in an elaborate whole. One of the reasons why I'm so fond of Parry. Though he wrote music for official occasions, there's often something humble and human if you listen more carefully.

Almost immediately, Parry switches back to "public mode" with the chorus "The monstrous sea" . Churning , monumental lines, trumpets calling forward, describing the "the orphaning waters wild and wide", sunken ships, a castle studded coastline and the moon, which controls the tides. "in the twinkling smile of his boundless slumber, to the rhythmm of oars....when the waters have glowed with blood, and hearts have laughed in then fight"....O Muse of our Isle, to thee, to thee !". Whether Bridges was connecting 17th century England to Victorain naval power, I don't know : the main thing is that, for Parry, a highly experienced sailor, this music heaves and surges like the sea and whatever that might represent. From this maritime imagery, the soprano and tenor duet "Love to love calleth" might seem to echo Tristan und Isolde. Hardly any composer anywhere in Europe was immune to Wagner, even those contra, so Parry can hardly be blamed for being aware of what was happening around him. All 19th century composers referenced German and Austrian musical tradition and built upon it : it would have been hard for any good composer to be isolationist. Parry's approach was individual : more understated than florid, gentler and more humane. Thus the Dirge for bass solo, "To me, to me, fair Goddess, come!" mourning again, possibly a hidden reference to George Herbert, though the section is dramatic and valedictory "Lament ! Lament, for when thy Seer died no song was sung". A final strophe with valedictory orchestral depth as the bass intones "We ne'er arise to see... our tears as dew".

The seventh section "Man born of desire" is the longest and perhaps the most elegaic. The chorus begins with hushed mystery but arises, accompanied by trumpets, in contemplation of the possible meaning of life. "(Man) striveth to know, to unravel the mind, that veileth in horror to vanquish his fate.... no ill shall be...whence he came to pass away...umade, lost for aye, with things that are not". As the Invocation draws to its cyclic conclusion, a more upbeat mood returns. Soprano, tenor and bass join the chorus for the ninth section "O enter with me the gates of delight"". Awakening from the "terror of night" the protagonists have reached "everlasting day". "Night hath unlocked the starry heaven for thee, the sea, the trust of his streams.......and death has no sting for beauty undying". As in the introduction, the different voices interwine gracefully. Music, thus invoked, brings new life. Infused with confidence, chorus andorchestra triumphantly celebrate "O Queen of sinless grace" (meaning Music, not a temporal Queen) which shall "with a myriad voiced song go forth.... with the joy of Man in the beauty of Love's desire".

Please see my other posts on Parry, especially the reviews of his English Lyrics CDs from SOMM

Saturday, 28 July 2018

Prom 17 - transcendental Parry, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Brabbins

Thunder and lightning above the Royal Albert Hall before Prom 17 with Martyn Brabbins conductingthe BBC National Orchestra of Wales in Hubert Parry, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst. Parry's Symphony no 5, the Symphonic Fantasia ,doesn't actually have much to do with the First World War, or Englishness for that matter. It's a brilliantly original work, which should be appreciated on its own musical terms. Parry's place in British music, and European music, deserves far more attention. The BBC's fixation with non-musical agendas reinforces cliché and shallow thinking to the detriment of the music itself.

Parry's Symphony no 5, the Symphonic Fantasia, is a brilliantly original work, looking forwards yet built upon Parry's very deep knowledge of his musical antecedents. In 1883, he had written of Schumann's Symphony no 4 that it "can be felt to represent in its entirety the history of mental and emotional conditions such as may be grouped around one centre.... the conflict of impulses and desires, the different phases of thought and emotion, and the triumph or failure of the different forces which seem to be represented all give the impression of ....being perfectly consistent in their relationship to one another."

Thus Parry's symphony - for it is a symphony in four movements (allegro, lento, scherzo and moderato) - encompasses infinite variety in tightly structured coherence. The programmatic titles, Stress, Love Play and Now, are in themselves nothing new, but Parry marks the various sub themes and developments not with conventional German or Italian terms, but with words like "brooding", "pity" and "revolt" which allow interpretive freedom. Its open-ended, free-spirited nature welcomes new performers, inviting them in, rather than imposing on them. This matters, since Parry held strong humanistic and ethical views. Please read my piece on Parry's The Soul's Ransom HERE. Some teachers teach students what to do, while others teach students how to think for themselves. Parry was the latter type : more self effacing than the dominant Stanford and in the long term perhaps a greater creative influence on other composers.

Though Parry in this symphony was thinking back to Schumann and Brahms, the innovative nature of this piece harks to Carl Neilsen's Symphony no 2 "The Four Temperaments", and quite possibly more. It's intricate patterns of theme, recapitulation, development and elongation show, says Jeremy Dibble, "a forward looking attitude to modern structural procedures. For this reason alone it merits a firmer place in the canon of cyclic works, and perhaps more important still it deserves to be more widely recognized as one of the finest and most assured utterances in British symphonic literature". If anyone can make a case for Parry as a beacon of modern British music, it would be Martyn Brabbins, whose repertoire spans the late 19th and 20th centuries. This was a powerful performance, very clearly thought through, much more coherent than when Siniasky conducted the piece at the Proms in 2010. While Adrian Boult and Matthias Bamert remain invaluable, Brabbins, with his alertness to the sophisticated inventiveness in the piece, reveals new insights.

Vaughan Williams The Lark Ascending is so extraordinary that even though we've heard it a million times, it still has the power to astonish. It's so moving that it always works, whatever the performance. Tai Murray, a former BBC New Generation artist, is technically gifted, shaping the long lines with great charm, suggesting the fragility of the lark. But there is more to this piece than refinement. I would have preferred more emotional engagement, bringing out the heart rending sense of Sehnsucht of really great performances. Perhaps if we hadn't heard this piece so often we might not expect so much, but how could we live without it ? But the magic of The Lark Ascending worked yet again : the Proms audience went wild with joy.

With Hubert Parry's Hear My Words, ye People (1894) the organ loft lit up. The organist was Adrian Partington, evidently enjoying the majesty of the Royal Albert Hall organ. Just as impressive was the BBC National Chorus of Wales, as focussed and as precise as they were in last week's Mahler Symphony no 8. Please read more about that here. Though Parry wrote Hear My Words, ye People for enthusiastic amateurs, with top notch singers like these, the anthems rang out with magnificent conviction. The soloists were Ashley Riches and Francesca Chiejina. This isn't an overblown extravaganza, but all the better for that as it shows the intimacy of Parry's style even when writing for choir, organ and (minimal) orchestra. Gustav Holst's Ode to Death (1919) blends voices and orchestra to create lush textures which suddenly ignite into crescendo. returning again to ethereal harmonies "Over the treetops I float thee along, over the rising and sinking waves, come lovely and soothing death, come with joy!". Harps and fine, bell-like tones in the orchestra suggest transcendence.

In Vaughan Williams's Symphony no 3 the "Pastoral" winds and bassoons murmured, as dark and impenetrable as smoke, a rather apposite image since the piece was written after RVW's experiences in the trenches, collecting bodies from fields which should have produced crops. A violin melody wafted upwards. Like the Lark it ascends, but its ascent seemed haunted. The natural trumpet in the second movement sounded deliberately hollow, like a trumpet blown by an ordinary soldier, perhaps not quite in tune. A horn repeats the motif : the last Post meets the last Trumpet at the End of Time. What might the robust dances in the scherzo represent ? Perhaps this is a threnody not only for those killed in the trenches but for an innocence that cannot return. Francesca Chiejina’s voice materialized from high up in the balcony, which in the Royal Albert Hall is very far away indeed. This is important because it creates a sense of distance. Whatever the soprano might signify, the sound should be otherworldly. That's why the song is mysterious vocalize. I don't even think it's meant to be an angel or anything quite so comforting, but a reminder that there are things that are beyond human comprehension and distances that can never be bridged.

But what of this Proms audience ? Even in the expensive seats, people were fidgetting, not paying attention, behaving as if they were at home in front of their TVs. Some walked out, even after Hear My words, ye People and the Ode to Death. Why weren't they paying attention to serious subjects and seriously good musicianship ? Therein lies the danger of marketing music as consumer disposable. Eventually audiences assume that as long as they've paid for something, they don't need to make an effort to put anything of themselves into the equation. Maybe what we need is marketing that respects the art it is supposed to serve. [Since writing this, I've heard from people who weren't able to attend because the Prom sold out almost immediately. All the more it's a shame that those who did get tickets didn't care enough about the music. The ones walking out after the choral pieces were cheerfully heading off to the pub. So much for the music and indeed for the subject ].

Please also read Robert Hugill in Opera Today

Wednesday, 25 July 2018

Ahead of Prom 17 Hubert Parry Symphony no 5

Hubert Parry's Symphony no 5 at Prom 17 Friday, along with Vaughan Williams and Holst. PLease read my review HERE and Robert Hugill's HERE. There's so much more to this programme than the usual clichés about the First World War. Just as there's much more to Parry than Jerusalem and sound tracks to royal events. So what if Parry died in 1918 ? What matters is his influence on British music,which runs deeeper than some expect. For one thing, Parry was not insular, but had an outlook which embraced continental European music. Please come back for my review of Prom 17, but some background on Parry's 5th (courtesy of Jeremy Dibble's seminal biography).

Parry's Symphony no 5 connects to Schumann's Symphony no 4 which we heard earlier this week in the 1841 version Brahms preferred. Since Parry respected Brahms so much, when Brahms died, he wrote a private and very moving tribute. Schumann's original "fourth" symphony was written in his glorious Liederjahre when a stream of masterpieces burst forth unstemmed. It's not the work of an immature composer, but rather of one who has so much to say that he needs to get it down quickly. "The important fact", wrote Parry in 1883 about Schumann 4 was "the work can be felt to represent in its entirety the history of mental and emotional conditions such as may be grouped around one centre.... the conflict of impulses and desires, the different phases of thought and emotion, and the triumph or failure of the different forces which seem to be represented all give the impression of ....beingperfectly consistent in their relationship to one another." Thus Parry's preferred title Symphonic Fantasia.

The titles of each movement, Stress, Love, Play and Now might mean different things to different people but had symbolic significance to a composer who cared deeeply about ethical and intellectual issues. Thus the complex but highly organized patterns of theme, capitulation and development. Some themes have titles like "brooding thought", "pity" and "revolt", like leitmotivs, but are defined by subtle tonal variations. "The elongated capitulation", writes Jeremy Dibble, "is decidedly Lisztian" and "the complex cyclic procedures" (in Schoenberg's .... Kammersymphonie published 1912) "shows a fascinating affinity with the processes in Parry's Symphony". Though it was unlikely that Parry knew this, it is all the more reason that it's remarkable how Parry "shows a forward looking attitude to modern structural procedures" adds Dibble. "For this reason alone it merits a firmer place in the canon of cyclic works, and perhaps more important still it deserves to be more widely recognized as one of the fineset and most assured utterances in British symphonic literature".

Thus the real programme in Prom 17, not "greatest hits" so much as British music on the verge of a new era. RVW's "Pastoral" isn't pastoral, and The Lark Ascending is pretty amazing, even if we've heard it a million times. Please also read my analysis of the secret programme behind the First Night of the Proms where the BBC's obsession with non-musical themes was trumped by deeper musical undercurrents. Please also visit the Hubert Parry Group on Facebook

Thursday, 26 April 2018

Maytime - Parry in Gloucester and London

Sir Charles Hubert Parry was, arguably, the founder of modern British music. Elgar didn't teach, except by example. Parry was both composer and academic, with a direct influence on a whole generation of composers who were to make British music what it is today - Vaughan Williams, Holst etc. etc. Parry was open minded and open spirited. There is a lot more to his music than Jerusalem and pieces for church and state occasions. Was Parry also the father of English song ? Please see my piece on Parry's English Lyrics.

So in this centenary of his death, it would be nice to commemorate him properly. Two concerts coming up in the next few weeks.. First, a gala evening concert at Gloucester Cathedral, Adrian Partington conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra, where

the Gloucester Choral Society will be joined by the Oxford Bach Choir

and the Philharmonia Orchestra in a programme that begins with Parry's I was Glad includes Parry's Ode to the Nativity and ends with Jerusalem. In between Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, Holst's Hymn of Jesus and Ireland Greater Love Hath No Man. This is part of a weekend celebration which will include a study day at Highnam House for true devotees.

Five days later, on 10/5, Partington brings the same forces to the Royal Festival Hall in London. I was Glad and The Ode to the Nativity are on the programme, and the same Vaughan Willliams but Holst and Ireland are dropped for Elgar's Cello Concerto witth Marie-Elisabeth Hecker. Not that anyone minds hearing that piece at all. I'll be at the Royal Opera House that night for the premiere of George Benjamin's new opera Lessons in Love and Violence. But if anyone's going, either to RFH or Gloucester, please let me know. There will be some Parry at the Proms too (Prom 17) , and one concert in the autumn at the Wigmore Hall, though in past years BBC Radio 3 has done all the symphonies and more. Parry isn't Box Office Hot Stuff and big choral numbers aren't easy to produce. So it's nuts to expect mass audiences and wall to wall hysteria. But that's just as well. Parry wasn't that kind of guy. Serious listeners can seek Parry out themselves, and listen, gradually absorbing his unique sensilibility. More on Parry and British music on this site and on my Hubert Parry Group on Facebook.

Tuesday, 3 April 2018

Hubert Parry English Lyrics vol 2 SOMM

New from SOMM recordings, the second volume from Hubert Parry's English Lyrics. Between 1874 and 1918, Parry wrote 74 songs in twelve collections, all titled "English Lyrics", two sets of which were published after his death. As Jeremy Dibble writes,"The generic title of English Lyrics symbolized more than purely the setting of English poetry (but) also an artistic manifesto and advocacy of the English tongue as a force for musical creativity shaped by the language's inherent accent, syntax, scansion, and assonance". German and French composers were quick to recognize how poetry could develop art song, and even set a great deal of Shakespeare (in translation and adaptation). Parry's interest in English lyrics opened new frontiers for British music. The prosperity of late Victorian and early Edwardian London fuelled the growth of audiences with sophisticated tastes, many of whom travelled and were up to date with music in mainland Europe. The splendid art nouveau interior of the Wigmore Hall attests to this golden age. Until 1914, it was the Bechstein Hall, connected to the Bechstein piano company who supplied pianos - and European music - to audiences beyond the choral society/oratorio market.

New from SOMM recordings, the second volume from Hubert Parry's English Lyrics. Between 1874 and 1918, Parry wrote 74 songs in twelve collections, all titled "English Lyrics", two sets of which were published after his death. As Jeremy Dibble writes,"The generic title of English Lyrics symbolized more than purely the setting of English poetry (but) also an artistic manifesto and advocacy of the English tongue as a force for musical creativity shaped by the language's inherent accent, syntax, scansion, and assonance". German and French composers were quick to recognize how poetry could develop art song, and even set a great deal of Shakespeare (in translation and adaptation). Parry's interest in English lyrics opened new frontiers for British music. The prosperity of late Victorian and early Edwardian London fuelled the growth of audiences with sophisticated tastes, many of whom travelled and were up to date with music in mainland Europe. The splendid art nouveau interior of the Wigmore Hall attests to this golden age. Until 1914, it was the Bechstein Hall, connected to the Bechstein piano company who supplied pianos - and European music - to audiences beyond the choral society/oratorio market. Sunday, 1 April 2018

Enlightenment ! Hubert Parry The Soul's Ransom

Hubert Parry's The Soul's Ransom (1906) has been called an "experimental masterpiece", one of the first successful English compositions to move away from the 19th century oratorio, foreshadowing the mature works of Parry's pupils, Vaughan Williams, Holst and Howells. "It is arguably a link work", wrote Bernard Benoliel, "between The Dream of Gerontius (1900) and The Sea Symphony (1909)". Parry was a scholar who revered the work of Heinrich Schütz, and also of Johannes Brahms. In The Soul's Ransom (1906) he blends together elements of very early German baroque with the (then) fairly modern master, adapting the instrumental and vocal style forms of very early German baroque and forms that were still relatively modern at the turn of the last century, "welding them into a structure where the effect is that of a terse and highly organic symphonic poem in four sections. The orchestra in the linking interludes and postludes functions as a ritornello, whilst the choruses, mostly in four parts, have a knotty quality which gives overall contrapuntal fabric a pre Bachian sense of movement".

"Structurally", writes Jeremy Dibble, "The Soul's Ransom is the most concise of all Parry's ethical choral works in its four-movement design and there is at times a more convincing adaptation of Baroque "style-form". This is true of the affecting recurrences of the clue-theme symbolizing comfort and compassion...... and even more so in the second movement where the three Beatitudes of the solo soprano....are answered in turn by the contrapuntal ritornello of the chorus."

The full title is The Soul's Ransom -The Psalm of the Poor, or Sinfonia Sacra, and in Parry's own words a "moral oratorio". Although he was an atheist, Parry's core values were closer to the true spirit of Christianity than to the image of the composer promoted in recent years to serve the state and establishment. We need to hear Parry the man and composer on his own terms. The texts are chosen from a range of sources, in the Hebrew and Greek testaments, connecting the Beatitudes with prophetic tradition, much in the way that Blake connected legend and protest in Jerusalem. Parry wrote his own words for the big final chorus, highlighting it with defiant glory, the organ booming. Dibble doesn't like the finale, calling it "anaemic" but for me, its stoic simplicity is its strength, much in the way that Brahms' German Requien draws power from being uneffusive, like pietist prayer.

"See now, ye who love the Light,

Ye shall not in darkness stray. ....

Truth will not die !

In every soul of man who lives,

The Spirit cannot lie!

To each and all the choice it gives

To rate the tempting world aright.....

To ward the ransomed soul to attain

To flawless harmony, divinely pure,

With that which was, and is, and shall be

Forever more endure"

The only recording was conducted by Matthias Bamert, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Della Jones and David Wilson-Johnson and the London Philharmonic Choir, in 1991, re-issued more recently by Chandos. The orchestral introduction has majestic sweep, suggesting the tides of the ocean. "Who can number the sands of the sea, the drops of rain and the days of Eternity" sing the chorus. The shifting textures suggest the vastness of the universe and the "multitudes" on earth. "Hear ye this, O ye people, the inhabitants of the World" sings the bass baritone with great portent. "Man that is in honour, but understandeth not, is like the beasts that perish!" Parry sets only three of the Beatitudes, but chooses them carefully : Blessed are ye poor, blessed are ye that hunger and Blessed are ye, when men revile you and persecute you. To further the point, the chorus sings "Man liveth not by bread alone". Bass and chorus recount the Prophecy of the Bones (Ezekiel 37, 1-14). "The people who walked in Darkness" sings the soprano, chorus and orchestra thronged behind her, "have seen a great light.". What is that light to which Parry's texts refer, and the prophecy that cannot be fulfilled on this earth ? In Christian teaching, we think we know the answer, but Parry suggests a more esoteric, more inclusive "Enlightenment". Close, indeed to Mahler's Symphony no 8, with its recurring images of "Accende lumen sensibus" and the "Veni Creator Spiritus" (the idea of enlightenment as creative force). Both Mahler 8 and Parry's The Soul's Ransom were completed in 1906. Pure coincidence. Neither composer might have been aware, but both were onto something good. The words "Soul's Ransom" are Parry's own, suggesting that he might have equated "darkness" with ignorance and suffering, "light" being wisdom and moral courage.

Tuesday, 13 February 2018

Hubert Parry Choral Festival, Gloucester

The Gloucester Choral Society host a choral festival honouring Charles Hubert Parry on the 100th anniversary of his death. Parry was perhaps the finest British composer in the generation before Edward Elgar, and, as Director of the Royal College of Music, helped shape 20th century British music, in particular the music of John Ireland, Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Parry's Jerusalem is almost our National Anthem. But the song, like the poem by William Blake that inspired it, is all too often misunderstood. (Please read my piece on it HERE). Though born to privilege, Parry's sympathies lay closer to Blake's than to the Establishment. It's fitting, then, that the GCS Festival begins with a Come and Sing Workshop led by Adrian Partington, where singers of all abilities will be welcome to sing Parry's Blest Pair of Sirens, and other pieces like Ireland's Vexilla Regis, Holst's Turn Back O Man and Vaughan Williams’sa Towards the Unknown Region.

On Saturday, 5th May, a gala evening concert will be held at Gloucester Cathedral, where the Gloucester Choral Society will be joined by the Oxford Bach Choir and the Philharmonia Orchestra in a programme that begins with Parry's I was Glad and ends with Jerusalem. Along the way, Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme by Tallis, Holst's Hymn of Jesus, Ireland's Greater Love hath no Man and Parry's Ode to the Nativity. Earlier on, an afternoon recital with Ashley Grote, the noted organist, at St Peter's Catholic Church in Gloucester with Parry's Chorale Fantasia on O God, our help in ages past, his Fantasia and Fugue in G and his Choral Preludes on Martyrdom and Eventide plus organ music by Vaughan Williams, Holst and Ireland. On Sunday, Eucharist and Evensong at Gloucester Cathedral will be celebrated with music by Parry,Vaughan Williams, and Howells

Perhaps the most unique event for true Parry devotees will be the all-day study day on Monday 7th at Highnam, which isn't generally open to the public except by arrangement. Highnam House was built in the 16th century, and extensively restored by Thomas Gambier Parry, the composer's father, who built the Church of the Holy Innocents, a gem of Victorian architectural excellence. (There's a street named after him in Gloucester). Professor Jeremy Dibble , Parry's biographer and an authority on British music, will give a talk on Parry's choral music. There'll also be a recital, and an Evensong in the Church, which will include Parry's Magnificat and Nunc Dimmitus, Vaughan Williams's Antiphon and Parry's Chorale Prelude on Hanover.

More details here from the Three Choirs Festival website

Sunday, 24 July 2016

Three Choirs Festival Gloucester Elgar Parry

The Three Choirs Festival 2016 launched in glory at Gloucester Cathedral with Parry's Jerusalem and Elgar's The Kingdom. The "Holy City and The Heavenly Kingdom", a brilliant pairing which expresses what the Three Choirs Festival represents. For three hundred years, the Three Choirs Festival has stood not only for musical excellence but also for communion, in the deepest sense of the word, bringing people together in the celebration of a glorious ideal.

This wasn't the usual Jerusalem in its famous setting by Elgar but Parry's original, believed lost for decades until uncovered by Jeremy Dibble, whose 1992 biography of Parry restored Parry's status and reputation – essential reading. Parry's orchestration isn't as lush as Elgar's, but the original is worth hearing for that very fact: Parry focuses on the questioning and on the irony in Blake's visionary poem. By setting the first verse for a single singer, Parry's setting emphasizes the provocative nature of Blake's conception. "And did those feet in ancient time walk upon England's mountains green?". In the full choral version, we get so carried away by crowd enthusiasm that we don't question. In Parry's version, however, Blake's irony is made more clear. And was Jerusalem builded here, among these dark Satanic Mills?" Bluntly, the answer is "No" So much for simplistic certainties. We may not get the glorious flourishes of Elgar's orchestration, but we do get an insight into Parry. Please read my piece on Jerusalem HERE.

In Elgar's The Kingdom, the apostles are about to embark on their journey which still continues 2000 years later. For all the grandeur and vast forces involved, at its heart, the piece is humble though assertive. The apostles are ordinary men serving a higher cause. Saints aren't superhuman beings but human beings inspired to do extraordinary things, inspired by faith and love.

Elgar dreamed of writing a trilogy of oratorios examining the nature of Christianity as Jesus taught his followers, using the grand context of the Edwardian taste. In The Apostles, Jesus sets out his beliefs in simple, human terms. Judas doubts him and is confounded. In The Kingdom, the focus is more diffuse. The disciples are many and their story unfolds through a series of tableaux, impressive set pieces, but with less obvious human drama. The final part would have been titled The Last Judgement, when World and Time are destroyed and the faithful of all ages are raised from the dead, joining Jesus in Eternity. The sheer audacity of that vision may have stymied Elgar, much in the way that Sibelius's dreams for his eighth symphony inhibited realization. Fragments of The Last Judgement made their way into drafts for what was to be Elgar's third and final symphony, which we now know in Anthony Payne's performing version. There are familiar themes from The Apostles in The Kingdom, so context helps. But the fact that the trilogy wasn't completed is in itself a refection on the fact the mission isn't complete and won't be until the End of Time, hopefully not in the foreseeable future, though things might not quite seem that way sometimes. Please read HERE about The Apostles at the Three Choirs in Worcester in 2014.

The Kingdom unfolds in a dignified procession, a series of tableaux each savoured witha measured pace, the intervals between them providing pauses for contemplation. Interestingly, The Kingdom focuses on female figures. Does this reflect Elgar's Catholicism, and his personal beliefs? The contralto has lovely passages, and the soprano has the glorious "The sun goeth down" and dialogues with the solo violin.

At Gloucester Cathedral last night Adrian Partington conducted the combined choruses of the Three Choirs, the Philharmonia Orchestra with soloists Claire Rutter, Sarah Connolly, Ashley Riches, and the youthful Magnus Walker, replacing James Oxley at short notice. I booked my tickets months ago, but unexpectedly couldn't attend. You'd think ticket returns would be as valuable as gold, but I was so fortunate to be able to give mine to very cherished friends, not Elgar aficionados, but good and decent people, who had a wonderful time. For me, sharing the gift of the Three Choirs is almost as good as being there!

Saturday, 28 May 2016

Hubert Parry and the Battle of Jutland

Commemorations this weekend for the Battle of Jutland, which took place 100 years ago this week. The British navy seemed invincible, Admiral Jellicoe tipped to become the Nelson of his age. The Dreadnoughts were the largest warships ever built, and the Battle of Jutland was the biggest naval skirmish in European history. With the Army bogged down in the Somme, the Royal Navy was to claim spectacular victory. Above, the warships sailing in neat, textbook formation., guns blazing. What went wrong ? So much had been invested in superstructure that simple, human procedures were overlooked. Below decks, the men loading the guns had so little space to manoeuvre that they cut corners. When the munitions stores ignited, the ships exploded and sank rapidly. In the midst of war, the government had to maintain that Jutland was a victory. This week, the Royal Navy announced the building of vast new aircraft carriers that "will make enemies think twice about starting war". (more here) But the very nature of warfare has changed, as the Russians discovered in Afghanistan, and the Americans in Vietnam. We only need to follow the news. On the open seas, where there is no cover and no fallback position, it might not be a good idea to concentrate resources in one place. On the centenary of the Battle of Jutland, should we reflect ?

Charles Hubert Parry's The Chivalry of the Sea - a Naval Ode, was written for a concert on December 12th 1916, commemorating the 6,000 men who died on the night of 31st May and 1st June. The text, by Robert Bridges, is dedicated to Charles Fisher, a graduate of and don at Christ Church, Oxford, a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who went down with HMS Invincible when it blew up. The photo below shows the Invincible as it sank, with Fisher and 1,025 men. We don't see the massive plume of smoke, captured in other photos. The ship is already part submerged.

Bridges' text might glorify sacrifice. But as Lewis Foreman has said, Parry was a born sailor, "never happier than when running before a prevailing wind", sailing in his small two-master even to Ireland. A sailor knows the sea and has no illusions about its power. Parry's Chivalry of the Sea begins in the depths with a sonorous undertow from which the brighter "chivalry" theme emerges for a moment, soon dissipating like foam on waves, whose strong undercurrents emerge again in a long passage in the midst of the verse. The orchestral surge continues behind the lines "Over the warring waters". No question here who's really boss.

The second verse, in which Bridges describes the "staunch and valiant hearted" who eagerly rush to war, is set with conventional brightness, bright and eager, but Parry repeats the word "war" three times to Bridges' single instance, lest we think the men are off on jolly jaunts. In the final verse, Parry has the measure of the occasion. The "surging waves" in the orchestra return, and the mood is more doleful. "in the storm of battle, fast-thundering upon the foe, ye add your kindred names to the heroes of long ago, and mid the blasting wrack, in the glad sudden death of the brave....ye lie in your unvisited graves". Although the choral setting is lush - the voice of the masses - Parry sets the word "sudden" with a chill. Perhaps he intuited the horror of Jutland. At least those blown to atoms at Jutland didn't suffer long. But some of them were little more than children. Please read the comment below - Parry's godson was one of the only 6 survivors of The Invincible. The young man's other godfather was Richard Wagner, no less !

.jpg)