Perhaps the most intriguing programme in the whole Sibelius series with Sakari Oramo and the BBC SO at the Barbican, London. Three stylistic breakthroughs -

Sibelius Symphony no 2 and

Symphony no 7 and

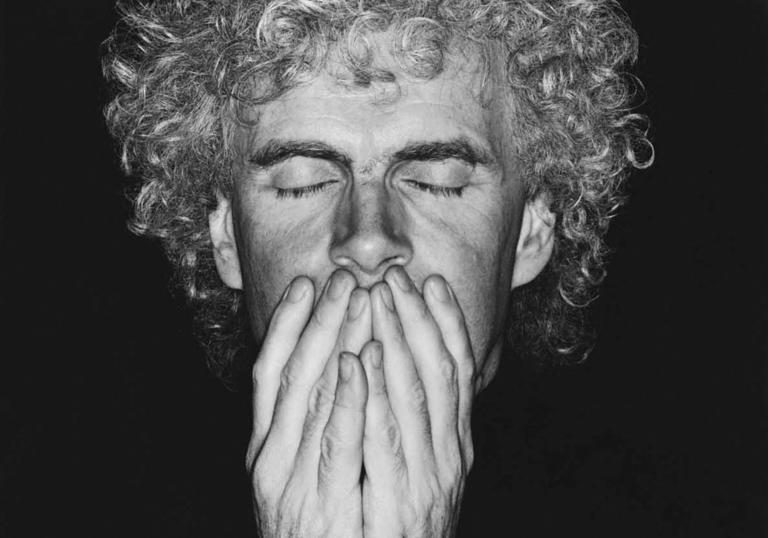

Luonnotar, with coloratura assoluta Anu Komsi, whose range and vocal flexibility is well suited to the piece.

Luonnotar is always a tour de force, but Komsi topped it off with Aare Merikanto's

Ekho, yet another vocal challenge. Pairing

Luonnotar with Ekho was daring indeed. Though the two pieces complement each other well, they are tricky to programme together, given the technical difficulties in the voice parts. But this conductor, orchestra and soloist have worked together so often in this repertoire that they can pull the feat off, and well, too. They have been busy in recent weeks, with the Sibelius series (see below for links to my reviews of other concerts), with Soumi 100 and with the Esa-Pekka Salonen Total Immersion at the Barbican which coincided with Finnish Independence week, in which the Komsi twins sang Salonen's

Wing to Wing. A lot to take on board at one time! Luckily, the Salonen Total Immersion is being broadcast on BBC Radio 3 this week. More about Salonen to come.

So hearing Oramo conduct the BBC SO in early Sibelius (Symphony no 2), early middle Sibelius (Luonnotar) and late Sibelius (Symphony no 7) brings out the connections between them and throws into higher focus the overall traverse of Sibelius output.The year after Luonnotar, Sibelius was to explore ocean imagery again in The Oceanides, whose Finnish title is Aallottaret, or "Spirit of the Waves", just as Luonnotar was the Spirit of Nature, tossed by waves. Luonnotar also marks a rebirth of a kind for Sibelius after the difficult period from which came the dark Symphony no 4. Mahler's works form a huge, coherent whole, but so too do the works of Sibelius when presented with the intelligence that Oramo has brought to this series.

Luonnotar was the Spirit of Nature, Mother of the Seas, who existed before creation, floating alone in the universe before the worlds were made "in a solitude of ether". Descending to earth she swam in its primordial ocean for 700 years. Then a storm blows up and, in torment, she calls to the god Ukko for help. Out of the Void, a duck flies, looking for a place to nest. Luonnotar takes pity and raises her knee above the waters so the duck can nest and lay her eggs. But when the eggs hatch they emit great heat and Luonnotar flinches. The eggs are flown upwards and shatter, but the fragments become the skies, the yolk sunlight, the egg-white the moon, the mottled bits the stars.

The orchestra may play modern instruments and the soprano may wear an evening gown, but ideally they should convey the power of ancient, shamanistic incantation, as if by recreating by sound they are performing a ritual to release some kind of creative force. The Kalevala was sung in a unique metre, which shaped the runes and gave them character, so even if the words shifted from singer to singer, the impact would be similar. Sibelius does not replicate the metre though his phrases follow a peculiar, rhythmic phrasing that reflects runic chant. Instead we have Sibelius’s unique pulse. In my jogging days, I’d run listening to

Night Ride and Sunrise, finding the swift, "driving" passages uncommonly close to heart and breathing rhythms. It felt very organic, as if the music sprang from deep within the body. This pulse underpins Luonnotar too, giving it a dynamism that propels it along. They contrast with the big swirling crescendos, walls of sonority, sometimes with glorious harp passages that evoke the swirling oceans.

But it is the voice part which is astounding. Technically this piece is a killer – there are leaps and drops of almost an octave within a single word. When Luonnotar calls out for help, her words are scored like strange, sudden swoops of unworldly sounds supposed to resound across the eternal emptiness. These hint at the wailing, keening style that Karelian singers used. This cannot be sung with any trace of conservatoire-trained artifice: the sounds are supposed to spring from primeval forces. After the duck approaches in a quite delightful passage of dancing notes, the goddess expresses agony for its predicament. Those cries of "Ei! Ei!" – and their echo – sound avant-garde even by modern standards. The breath control required for this must be formidable. Singing over the cataclysmic orchestral climax that builds up from "Tuuli kaatavi, tuuli kaatavi!" must be quite some challenge. The sonorous wall of sound Sibelius creates is like the tsunami described in the text, and the soprano is riding on its crest.

Luonnotar is a complex creature, godlike and childlike at the same time, strong enough to survive eons of floating in ravaged seas, yet gentle enough to cradle a hapless duck. The singer needs to convey that raw primal energy, yet also somehow show the kindness and humour. The sheer physical stamina of singing this tour de force probably accounts for its relative rarity on the concert platform. Luonnotar swam underwater for centuries, so a soprano attempting this must pray for "swimmer's lungs". The last passages in the piece are brooding, strangely shaped phrases which again seem to reflect runic chanting, as if the magical incantation is building up to fulfillment. And indeed, when the creation of the stars is revealed, the orchestra explodes in a burst of ecstasy. The singer recounts the wonder, with joy and amazement: "Tähiksi taivaale, ne tähiksi taivaale". ("They became the stars in the heavens!"). I can just imagine a singer eyes shining with excitement at this point - and with relief, too, that she’s survived! As Erik Tawaststjerna said, "the soprano line is built on the contrast between … the epic and narrative and the atmospheric and magical".

In his minimalist text, Sibelius doesn’t tell us that in the Kalevala, Luonnotar goes on to carve out the oceans, bays and inlets and create the earth as we know it, or tell us that she became pregnant by the storm and gave birth later to the first man. But understanding this piece helps to understand Sibelius’s work and personality. Like the goddess, he was struggling with creative challenges and beset by self-doubt and worry. Perhaps through exploring the ancient symbolism of the Kalevala, he was able in some way to work out some ideas: in

Luonnotar, you can hear echoes of the great blocks of sound and movement in the equally concise

seventh symphony.

In each concert in this Oramo/BBCSO Barbican series, other composers have been included for comparison and contrast. Now, at the end of the run we're looking ahead to the future. Aare Merikanto (1893-1956) was the son of Oscar Merikanto (1868-1924), also a composer and a contemporary of Sibelius. Please read more

HERE about mid 20th century Finnish music (Susanna Mälkki/Helsinki Philharmonic in December). Oramo conducted Aare Merikanto's

Ekho (1922), and Komsi sang. But enough for now, I'm knackered. I'll write about that tommorow .when I have more time. And

here is my bit on Merikanto's Ekho, as promised !

Other concerts in the Oramo Sibelius series with the BBC SO at the Barbican:

Finland Awakes ! Finnish centenary celebration

Sibelius 4 and 6, Anders Hillborg

Sibelius 3 Ravel Franck and Schmitt