The Royal Opera House was right to warn audiences about Donizetti Lucia di Lammermoor. Donizetti is dangerous. In his time, the glass harmonica, which gives this opera its unique character, was believed by many to induce insanity. Its surreal drone would have added an extra frisson of danger to early performances, enhancing the dramatic impact. The full impact may be lost on modern audiences used to horror movies and the ondes martenot, but the instrument serves a purpose. Donizetti's audiences might well have gone to the theatre half-believing that the glass harmonica might induce hysteria. Might Lucia's madness be contagious? If they don't turn into zombies first. Lucia's family is falling apart, so they use her to restore their fortunes, much in the way one might trade chattels. It hasn't occured to them that their troubles were caused by feuds and an obsession with form and status. Lucia has no escape other than to go off the rails. It's not a pretty story.

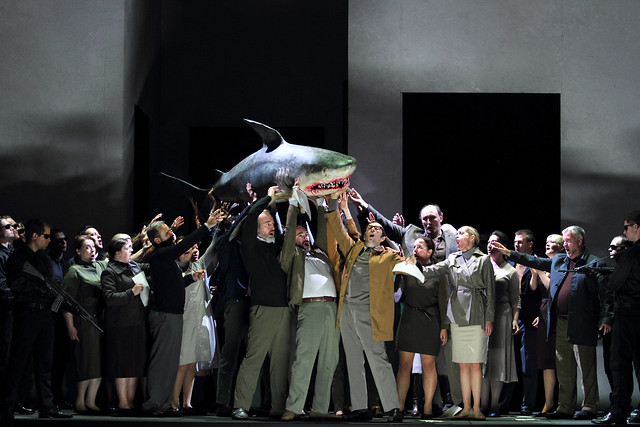

The mad scene for which the opera is famed is central to its meaning. Of course it's gruesome. Lucia stabs Arturo on the wedding night. In societies where women are traded like possessions, the act of deflowering signals ownership. This time, the bride penetrates the bridegroom, and he dies. Whether Lucia's actually having an abortion or not is largely irrelevant. This marriage won't yield fruit. Audiences just need to wake up to the fact that opera is about human emotion, and human feelings are messy.

Lucia is clearly unstable long before the wedding. It's significant that she's lost her mother, and presumably doesn't want to share whatever fate befell her mum. Thus she identifies with the ghost and falls suddenly in love when Edgardo kills a wild animal at her feet. Blood, love and death inextricably linked. Freudian undertones long before Freud. Lucia's psycho-sexual problems go back a long way. She's an accident waiting to happen. After Manon Lescaut, a man was enraged because he'd taken a young girl to the show and was furious that she'd seen something sexual. That says less about the production than about the man himself and his own psycho-sexual hangups. Plus the fact he didn't know beans about the opera.

Donizetti set the opera in the Highlands because at that time Scotland symbolized the borders of civilization, where primitive extremes prevailed. This Scotland was largely the creation of Walter Scoitt's imagination. Scott himself was a buttoned-up urbanite who wanted Scotland tamed by Victorian values. So there's absolutely no reason why the setting shouldn't be Victorian, since Donizetti was dealing with emotional truth. Yet again, the onus is on the audience to understand the work and - horror of horrors - to realize that there is more to an opera than the first line of the synopsis.

Every performance, every production, reflects someone's interpretation of a work of creative imagination. Unfortunately, in ths age of narcissism, the consumer is king. But the world does not exist as a Gigantic Selfie. In theory, we go to the opera to learn , and we learn by taking on board new perspectives, right or wrong. Now productions are judged by the baying, booing mob, some of whom seem to get their kicks not from art but from socially sanctioned abuse. If audeinces don't want blood, sex and drama, they should stick to the circus (and ignore the sufferings of animals and underpaid staff) or to cartoons (where there's a lot more violence than some realize - think Tom and Jerry) FULL REVIEW appears shortly in Opera Today.