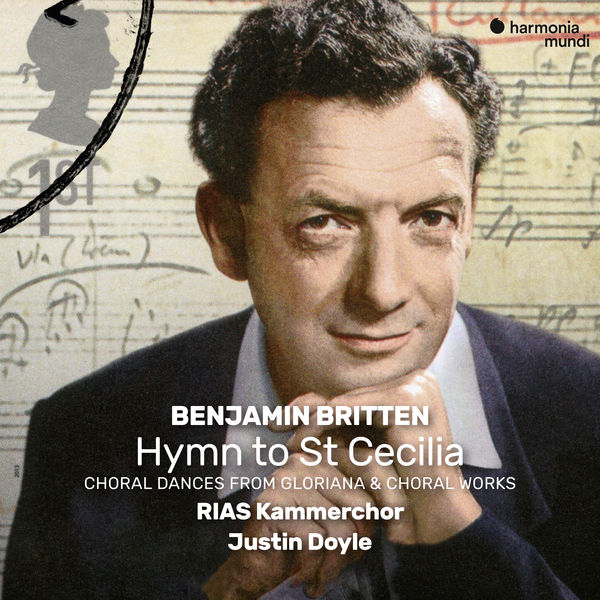

Benjamin Britten Choral Songs from RIAS Kammerchor, from Harmonia mundi, in their first recording with new Chief Conductor Justin Doyle, featuring the

Hymn to St. Cecilia, A Hymn to the Virgin, the

Choral Dances from

Gloriana, the

Five Flower Songs op 47 and

Ad majorem Dei gloriam op 17. This new release extends RIAS Kammerchor's engagement with British repertoire, established when they recorded Britten's

Sacred and Profane together with songs by Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Charles Stanford, with former Chief Marcus Creed in 2013. This new collection is particularly valuable because it focuses on works Britten wrote at a formative period in his career which even now is relatively unexplored.

Britten's

Hymn to St Cecilia op 27 is one of the classics of modern choral repertoire. It's not an "easy sing", lines and parts interwoven in inticate patterns. This hymn had great personal significance for Britten, who was born on St. Cecilia's Day. It is relevant that this was while he lived abroad : its connections to English polyphonic tradition show where his heart truly remained. St Cecilia was a singer who was matryred for her faith, hence the symbolism implicit in the text, by W H Auden.

"

Blessed Cecilia, appear in visions/

To all musicians, appear and inspire/

Translated Daughter, come down and startle/

Composing mortals with immortal fire."

This refrain repeats through the three sections of the piece, and are sung in unison, underlining its meaning. Auden extends the imagery to include Aphrodite, rising full-formed from the sea, and a more obscure reference (possibly from Dante), "

around the wicked in Hell's abysses/The huge flame flickered and eased their pain." Britten picks up on this for the scherzo section, where bright, short phrases flicker, like flames, in quick succession. The hymn is as much for all artists in times of persecution as it is for the saint, given that Britten was acutely aware of the impact of Nazism on composers and others in the Europe he'd thought he'd left behind. The final section is characterized by "o" sounds and vowels, which resonate, like bells, an aural image emphasized by the sudden descent into solo parts, evoking sacred form. The RIAS Kammerchor perform Britten's

Hymn to St Cecilia so it flows fluidly, the parts so well balanced that they blend without losing clarity.

Britten wrote his

Hymn to the Virgin at the age of sixteen, revising it in his early years at the Royal College of Music. Nonetheless it is not juvenilia, but a sophisticated use of double chorus, one singing in English, the other responding in Latin, creating an echo effect as if the past were resurfacing in the present. In the final verse, the parts divide, singing the text together.

This recording is also valuable because it features the

Choral Dances from Britten's

Gloriana. The opera is sadly still misunderstood, and the dances in the Second Act come in for criticism, so hearing them on their own as a sequence shows their merits. This also demonstrates their role in the opera, which is not to further the obvious drama between Eliuzabeth and Essex but to focus on the Queen and her subjects, and the national interests that made her give up Essex for England. The good folk of Norwich are a symbol of the nation, and their loyalty is genuine. This fits in, too, with Britten's core beliefs in the value of local community : at Aldeburgh, he did more for community music theatre than anyone since the Renaissance. In contrast, the courtiers who surround the Queen are sycophants and hypocrites. The courtiers may sneer at the peasants, but the Queen recognizes sincerity. Presumably the new Queen Elizabeth got the message. She was personally fond of Britten and gave him her support, much to the chagrin of those who thought him an outsider.

In the opera, the

Choral Dances also underline the fundamental role of English tradition in Britten's music. This structure is reminiscent of earlier form, and shows Britten's understanding of style. The first three dances are a masque within a masque. "Time", "Concord" and "Time and Concord", moving from liveliness to serenity to joy. The women's voices of the RIA Kammerchor sing "The Country Girls", while the men sing "Rustics and Fishermen", and come together again for the "Final Dance of Homage", here beautifully parted.

Britten's

Five Flower Songs op 47 (1950) sets poems by Robert Herrick, George Crabbe, John Clare and an anonymous folk song. Britten creates a bouquet, bringing together colours in varied combinations. "To Daffodils" is swift, for daffodils don't linger, while "The Ballad of Green Broom" alternates doughty rhythms with longer, lighter lines, men's voices for the wood, womens for leaves, so to speak, the song ending with a witty flourish. In "The Succession of the Four Sweet Months" (Herrick) the parts define each month. The parts combine in "Marsh Flowers", strong colours spread along lines that end in a sudden upbeat, and in "The Evening Primrose" stretch the lines so they descend slowly into slumber.

With

Ad majorem Dei gloriam (AMDG) we return to Britten from roughly the same period as

Ballad of Heroes op 14, the

Violin Concerto op 14 and

Young Apollo op15, all of which did not receive much attention until later years. In the case of the

Violin Concerto, now regarded by many as a masterpiece, the reason may be that it expressed despair so intense that Britten could not yet process. The reason for the suppression of AMDG may have more to do with the fact that the solo SATB version can't achieve the colour a larger ensemble can bring to it. But there are deeper undercurrents here, too. The texts are by Gerald Manley Hopkins. What drew Britten to these poems of extreme mystical devotion ? Since Catholic Emancipation wasn't achieved until 1829, and the order itself was suppressed until around that same time, Jesuit principles of intellect and independence threatened more conservative minds. Furthermore, Hopkins' poetry was not published until after his death, a sign of humility before God. Hopkins may have been, for Britten, the quintessential artist as outsider, who endured suppression for the greater glory of his Art.

These songs are difficult to perform, but RIAS Kammerchor carry them off extremely well. Again, the fine balance between voices creates a lustrous sheen which enhances a mystical sense of rapture. In "Prayer I" ("Jesu that dost in Mary dwell") the voices unite for the last line "To the greater glory of Thy Son : Amen", the last word extended, like a prayer. Even more beautiful is "Rosa Mystica", where the male voices chant, as if at Mass, the women's voices dancing above the steady pulse of prayer. The women's voices take up the chant with greater elaboration. Britten sets "God's Grandeur" with brisk pulsating rthyms from which outbursts of energy emerge, like shouts of joy. With "Prayer II", a hushed, contemplative mood returns, the flow of the lines illustrating the image of a fountain linking God and Man. When the men sing "

I repent of what I did", the line stands out, emphasizing humility. "O Deus, ego amo te" is a tender love song ; for Hopkins, the object being God, for Britten, perhaps someone human, The word Amen stresses the first syllable so it explodes like a shout. The Jesuit order was founded by soldiers, and organized on quasi-military lines. Hopkins writes unorthodox marching rhythms into his poem "The Soldier", which Britten respects, starting with the ejaculatory "YES!" (in capitals in the original poem) For Hopkins, the poem is a celebration of vigour in imitation of Christ. But Britten, and readers of A E Housman, may read other connotations in the line ".....s

éeing somewhére some mán do all that man can do,

For love he leans forth, needs his neck must fall on, kiss, And cry ‘O Christ-done deed!".

If man is the image of God, kissing a man cannot be a sin. In this context, the final song "Heaven-haven" may be a love song, too, and to someone quite specific. The text is simple and direect, Britten's setting calm, with no fear of the "Love that dare not speak its name" in the words of Lord Alfred Douglas. Imagine the rage of homophobes and those jealous of Britten and Pears in an era when homosexuality was illegal. Britten may not have published the songs, but he didn't destroy them, aware that some day they would be understood as a testament.