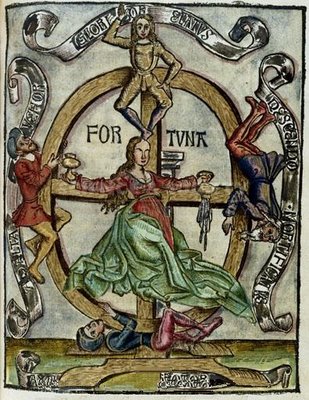

O Fortuna ! As the Wheel of Fortune turns...... The BBC Concert Orchestra is Cinderella in the stable of BBC orchestras, relegated to workhorse gigs, TV dramas and the resolutely anti-intellectual fare the Proms (and the BBC in general) seem to be descending into. Then along comes Carl Orff Carmina Burana (1936) at Prom 69. Real music, and vividly realized. Carmina Burana is a strange beast, a pseudo-medieval extravaganza mixing vulgarity with piety. Everyone knows Carmina Burana, even if they think it's the sound track

to TV ads and satires like THIS.

Because it's so familiar, responses are coloured by "TV thinking", superficial, ill informed and kneejerk, like the cliché that Orff didn't oppose the Nazis, except in his dreams. But Orff was a conundrum, a complex person who concealed his inner life even - and perhaps especially - from himself. The joyous barbarism appeals on a primitive level, connecting to primal emotions. One could draw a direct line between Carmina Burna and what was, arguably, Orff's greatest gift to mankind, his Schulwerk and legacy of expressive music-making in circles way beyond the western classical music mainstream.

Carmina Burana is brutal, because the Middle Ages were brutal. If you were lucky you got high on ergot and died by the age of 40. Dionysian riot probably meant even more to grim lives. The picture left is Breughel, The Battle between Carneval and Lent. Eat, drink and be merry for Lent is coming and with it, hardship. And you might not be around by Easter. Orff was no intellectual, but on an intuitive level he may have made the connection between the dark side of the Middle Ages and the madness of theThird Reich. There was a lot of "medievalism" in music in this era. Think Frank Martin, Walter Braunfels, W A Hartmann and Arthur Honegger. Perhaps we too are living "at the End of Time", fighting off the Apocalypse with mindless hedonism.

And so, back to Prom 69, the BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by Keith Lockhart. This performance played to the BBC CO's strengths, bringing out the cinematic qualities in the piece. The "big numbers" could have come straight out of Hollywood, the brass blazing and the big drums booming. I was even more impressed, though, by the faux-lyricism of the quieter sections where the orchestra played quietly, and the choruses twittered the "meadow" songs prettily, like birds in a Rudolf Ising cartoon. A poisoned Spring! This was far more chilling in many ways than simply forcing the rhythms for effect. Delightfully vernal "antique" trumpets, and violins sounding like lutes.

.

Best of all, though, was the singing. Benjamin Appl sang the baritone part withe brightness and natural colour: a genuinely interesting voice intelligently used. I learned the piece from Fischer-Dieskau, who was wonderful but a bit uncomfortable . Drunken boor wasn't his style. Thomas Walker sang the Olim lacus colueram well. By the end of the Tavern sequence, everyone's pissed, singing parodies of "normal" song. Just the right touch of inebriation. After that, can we take the Minnelied courtliness at face value? And what are Communion bells doing here? What is being consecreted or sullied, as the case might be? Orff's pulled another fast one. "Tempus est jocundum". Lovely singing by Olena Tokar, but the moment doesn't last. Yet again we're thrown back on the "mob", the brusqueness of the music for baritone (not a "boy") and massed male voices. "Venus, Venus, Venus" they called, a testosterenoe fix heralded by the big timpani and the return of O Fortuna. The wheel has turned. with a chill. The BBC Symphony Chorus and the London Philharmonic Choir did the honours, assisted by the Southend Boys' and Girls' Choirs.

Before Carmina Burana, Guy Barker's The Lanterne of Light. Everyone writes for Alison Balcom these days because she plays so expressively, but the piece itself is a bit pointless; perhaps if it had stuck to one or two Deadly Sins or done them all with more compression? Not really enough to sustain for too long.

Because it's so familiar, responses are coloured by "TV thinking", superficial, ill informed and kneejerk, like the cliché that Orff didn't oppose the Nazis, except in his dreams. But Orff was a conundrum, a complex person who concealed his inner life even - and perhaps especially - from himself. The joyous barbarism appeals on a primitive level, connecting to primal emotions. One could draw a direct line between Carmina Burna and what was, arguably, Orff's greatest gift to mankind, his Schulwerk and legacy of expressive music-making in circles way beyond the western classical music mainstream.

Carmina Burana is brutal, because the Middle Ages were brutal. If you were lucky you got high on ergot and died by the age of 40. Dionysian riot probably meant even more to grim lives. The picture left is Breughel, The Battle between Carneval and Lent. Eat, drink and be merry for Lent is coming and with it, hardship. And you might not be around by Easter. Orff was no intellectual, but on an intuitive level he may have made the connection between the dark side of the Middle Ages and the madness of theThird Reich. There was a lot of "medievalism" in music in this era. Think Frank Martin, Walter Braunfels, W A Hartmann and Arthur Honegger. Perhaps we too are living "at the End of Time", fighting off the Apocalypse with mindless hedonism.

And so, back to Prom 69, the BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by Keith Lockhart. This performance played to the BBC CO's strengths, bringing out the cinematic qualities in the piece. The "big numbers" could have come straight out of Hollywood, the brass blazing and the big drums booming. I was even more impressed, though, by the faux-lyricism of the quieter sections where the orchestra played quietly, and the choruses twittered the "meadow" songs prettily, like birds in a Rudolf Ising cartoon. A poisoned Spring! This was far more chilling in many ways than simply forcing the rhythms for effect. Delightfully vernal "antique" trumpets, and violins sounding like lutes.

.

Best of all, though, was the singing. Benjamin Appl sang the baritone part withe brightness and natural colour: a genuinely interesting voice intelligently used. I learned the piece from Fischer-Dieskau, who was wonderful but a bit uncomfortable . Drunken boor wasn't his style. Thomas Walker sang the Olim lacus colueram well. By the end of the Tavern sequence, everyone's pissed, singing parodies of "normal" song. Just the right touch of inebriation. After that, can we take the Minnelied courtliness at face value? And what are Communion bells doing here? What is being consecreted or sullied, as the case might be? Orff's pulled another fast one. "Tempus est jocundum". Lovely singing by Olena Tokar, but the moment doesn't last. Yet again we're thrown back on the "mob", the brusqueness of the music for baritone (not a "boy") and massed male voices. "Venus, Venus, Venus" they called, a testosterenoe fix heralded by the big timpani and the return of O Fortuna. The wheel has turned. with a chill. The BBC Symphony Chorus and the London Philharmonic Choir did the honours, assisted by the Southend Boys' and Girls' Choirs.

Before Carmina Burana, Guy Barker's The Lanterne of Light. Everyone writes for Alison Balcom these days because she plays so expressively, but the piece itself is a bit pointless; perhaps if it had stuck to one or two Deadly Sins or done them all with more compression? Not really enough to sustain for too long.