Martyn Brabbins conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra. at the Barbican in Ralph Vaughan Williams Symphony no 4 and Arnold Bax November Woods A good combination which had the potential to yield interesting insights in musical terms. So why does BBC Radio 3 management need to market this as "Remembering World War I" ? Neither piece has anything to do with war. Alas, BBC R3 seems hell bent on prioritizing non-musical agendas over music, to meet non-musical targets. Long term, this policy of dumbing down destroys real musical understanding. Better to treat audiences as adults who aren't afraid to think or listen.

Both Vaughan Williams's Fourth Symphony and Bax's November Woods are explorations of ideas that aren't so easy to put in prose : "internal landscapes" so to speak, that find expression in sounds and musical form. November Woods (1917) isn't about forests per se but forests as metaphors for emotion It's worth quoting Bax's (non-symphonic) poem Amersham, as the programme book does :

Storm, a mad painter's brush, swept sky and land

with burning signs of beauty and despair

And once rain scourged through shrivelling wood and brake,

And in our hearts tears stung, and the old ache

Was more than any God would have us bear.

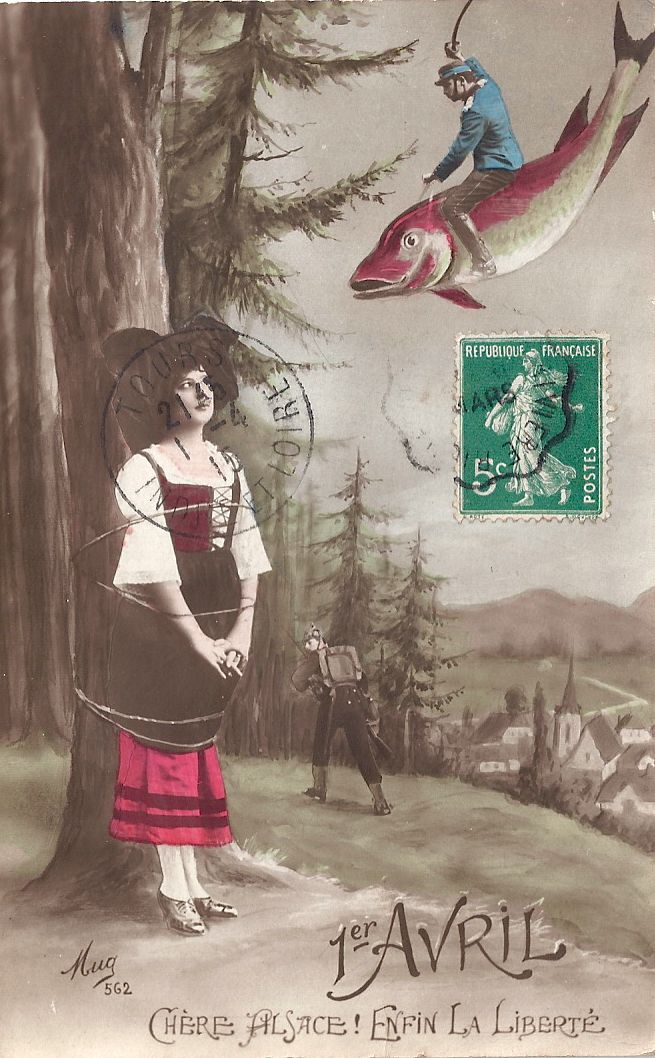

Here the musical forces were in the fore, the orchestra voicing whatever inner storm Bax might have sought to address. The introduction seems to surge and strain, driven by fast-flowing strings, lit by flashes of woodwinds and harp, darkened by violas, celli, oboe and bassoons. A theme energes, first from cor anglais, then more boldly by horn and then oboe and cello : a duality which could suggest many things, but is part of the very conception. Themes cool and warm, creating flux, but there's no easy resolution. The coda was hushed, mysterious, open-ended. November Woods is much more "modern" than you'd expect, connecting in this sense to other works of the period.

|

| photo : Jules Barbieri |

More brass in the second movement, marked andante moderato, but this time more restrained, the strings of the BBCSO murmuring en masse, from which the woodwind line rose, moving ever upwards. A sense of unease : tense pizzicato creating a fragile though regular beat. The flute melody, exquisitely played, had a poignant quality: painfully alone but unbowed. Wildness returned with the third movement, brass pounding, trombones creating long zig-zag lines. For a moment the tuba leads a trio with grunting bassoons. The term "scherzo" means "joke" but the humour here is darkly ironic. This colours the sprightly theme which follows : it's not escapist. With the figure I called "My God and King" the overwhelming thrust of the first movement returns, angular dissonances flying in all directions, clod-hopping ostinato suggesting grotesque horror. Again, no resolution, no easy answers. Perhaps we can guess why RVW dedicated it to Bax.

The contrast with the intensity and sheer musical quality of Vaughan Williams's symphony put Cheryl Frances-Hoad's Last Man Standing into place. This is a big work, running as long as the symphony, and was served up with lighting effects, props and a shower of objects which might be poppies, and co-ordinated dresses for composer and text writer. The piece was specially commissioned to mark the 1914-1918 war. But there is a lot more to war than pretty images. Much of the problem lies in the text, 15 verses on aspects of life in the trenches, by Tamsin Collison. Frances-Coad's setting illustrates well but is more sound effects than music. Entertaining enough, and certainly not mentally or emotionally challenging. But war is not entertainment. and never should be trivialized. We know, or should by now know, what it was like in the trenches, but no sign here of any reflection or personal insight. The baritone soloist, Marcus Farnsworth, did his best, as did the orchestra, but this piece bore all the signs of music-made-to-order. Millions died and suffered in the Great War, which re-shaped the whole world. To what avail ?

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-shropshirestar-mna.s3.amazonaws.com/public/FOGEW2OKMVFE7PSDYTDI4EL5XY.jpg)

_cropped_and_retouched.jpg/300px-Charles_Hamilton_Sorley_(For_Remembrance)_cropped_and_retouched.jpg)

.jpg)