"Tradition ist nicht die Anbetung der Asche, sondern die Bewahrung und das Weiterreichen des Feuers" - Gustav Mahler

Saturday, 1 February 2020

Sunday, 30 September 2018

Monday, 26 March 2018

Debussy and Beyond - François-Xavier Roth, LSO Barbican

| Debussy and Stravinsky, 1910 |

On the centenary of Debussy's death, "Debussy and Beyond", with the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican,, conducted by François-Xavier Roth. This was the highlight of an unusually well planned series, examining Debussy from different angles. Anyone can programme mechanical "greatest hits" programes, but from Roth and the LSO we can expect much more musical nous. In "The Young Debussy", we heard the influences that shaped him, In "The Essence of Debussy", we heard well known pieces and the less well known, like the Fantasie for piano and orchestra,. This series has been challenging because it didn't spoonfeed, but presentedthoughtful challenges for further listening and contemplation. For "Debussy and Beyond", there could be dozens of possible contenders, since Debussy's influence on modern music is so extensive. Debussy changed the game, no less. He paved the way for others, whose music is very diffrent from his own, and continues to inspire. This evening's programme focussed on large ensemble, and on major works that would often be the backbone of most concerts. It lasted nearly three hours, but was so rewarding that time passed all too soon.

Homage to Debussy and also homage to Pierre Boulez, one of Debussy's finest interpreters and champions, who was born seven years and one day after Debussy died. Much has been written about how Boulez's Livre pour cordes morphed, or didn't morph, over 20+ years, so it's not worth repeating, save to say that it is "mega string quartet" scored for 16 first and 14 second violins, 12 violas, 10 cellos and 8 basses. The four main groups are multiplied into many parts, creating intricate polyphonic textures. Onto this a panoply of techniques, for further variety. Yet the whole piece lasts under 11 minutes. It's a model of tightly woven concision - nothing extraneous - precision. Roth conducted the LSO, so it came over as chamber music, albeit on a grand scale, the players interacting with precison and grace. Not "impressionism", in the "mood painting" sense of the word, but finely detailed complexity, extending Debussy's tonal ambiguity and chromatic adventure.

Though there's ostensibly little direct connection between Debussy and Bartók, both were pillars of twentieth century music, and cannot be ignored. Many others might have been included, but for practical, logistic reasons, this concert focussed on works for very large ensemble. Bartók's Violin Concerto no 2 BB117 (1937-8) served to balance the other two big pillars of the programme, Stravinsky's Chant du Rossignol and Debussy's La Mer, with Renaud Capuçon as soloist.. Capuçon's long solo passages were played with style, contrasting well with the striking orchestral backdrop. Since the LSO has a commendable commitment to new music, this was followed by the world premiere of Ewan Campbell's Frail Skies (2017), another work for very large orchestra including piano. I'd hesitate to call it a tone poem, though there are images in the music that suggest the forces of Nature. Though the title suggests the sky, I thought of waves in an ocean, carrying thousands of minute particles carried in their wake. The piece moves in cyclic fashion beginning and ending with solo cello surrounded by larger, darker forces, traversing other cyclic patterns along the way. High woodwinds added lightness, somnolent strings and brass added density. No young composer could compress as much into a short work as Boulez did with Livre pour cordes, but at least new work is being written, and new composers are finding their way.

Debussy and Stravinsky knew each other well. The photo above shows them together during the 1910 Ballets Russe season in Paris in 1910, when The Firebird was performed. For this programme, François-Xavier Roth included Stravinsky's Chant du rossignol, loosely based on Hans Christian Anderson's tale about a nightingale and a mythical Emperor of China. Given that Debussy was fascinated with Japanese and Indonesian culture, this was an inspired choice, connecting Debussy's eclectic interests and the craze for "primitive" non- western art, which made Stravinksy and Diaghilev sensation. French orientalism, which has a long past, was to stimulate numerous artists and composers, from Ravel to Picasso, to Messiaen and beyond. Recently Roth and Les Siècles gave a concert in Paris, which iuncluded a gamelan orchestra (read more here). With Chant du rossignol, Roth and the LSO open out a whole horizon to explore. In purely musical terms, Chant du rossignol is also apposite because Stravinsky blends exotic colour with lyricism. The nightingale is no Firebird, but its fragility is its strength. A violin sings for the mechanical nightingale, its elaborate trills deliberately formal. The flute sings for the real nightingale, singing with freedom and inventivenss. The Emperor, for all his wealth, cannot compete. The music that depicted him was dark and slow - basses and low timbred winds and brass, and tam tam, against which the "nightingale" shone ever more brightly. Exquisite detail in this performance, even in small figures, like trombone ellipses and the sensation of breeze (harps, strings, brass) at the very end.

François-Xavier Roth has conducted Debussy La mer so many times that it's practically his trademeark. He's even constructed whole programmes around it (please read more here). This time it felt valedictory. After that outstanding performance of Chant du rossignol, it was good to pause and reflect on Debussy and his legacy. La mer never loses its magic but seems to forever reveal new depths. The ocean covers most of the planet : different in different parts of the world, but always developing. A metaphor for music !

Thursday, 8 March 2018

Janáček From the House of the Dead, ROH and memories of Chéreau

|

| Scene from From the House of the Dead, Patrice Chéreau 2007 |

Mark Wigglesworth's conducting certainly played up the violence, and rightly so, since there's nothing cute about a society that needs gulags to keep people under control. Luckily for me, I learned this opera audio-only, from the Vaclav Neumann recording, rather than from Mackerras, so I think of it in terms of the music first. The first time I experienced the opera live was when Perre Boulez conducted the production directed by Patrice Chéreau : a historic event in many ways, impossible to forget. Boulez conducted with an unnerving intensity: red hot holds nothing back but ice-cold suggests invisible horrors too dangerous to contemplate. The tragedy of human suffering, so fundamental to Janáček's vision, grows ever more powerful in contrast. From the House of the Dead is actually more humane than some assume. Janáček cared about people. As Chéreau pointed out, what really pervades the opera for him is its implicit humanity. Under the harshness and violence flows surprisingly strongly a sense of “compassion”, as he puts it, which runs like a hidden stream throughout the opera, surfacing at critical junctures. It is also totally non-judgemental. Neither murderers nor guards are held to account, they simply exist. Thus the famous phrase near the end, “he too was born of a mother”.

At a discussion session after the performance I heard in Amsterdam in 2007, someone in the audience (beware that type) asked Chéreau why he didn't costume the prisoners in orange, to protest Guantanamo Bay. Quick as a flash, Boulez said: "We are in Holland. In Holland, Orange is the Royal House". In a nutshell, the art of visual literacy : images mean different things. Chéreau's prisoners could have been Everyman in their drab garb, in a set dystopian in its abstraction. The prisoners engaged in pointless, repetitive work (building a ship in landlocked Siberia) but it doesn't overwhelm the stage. Instead there's an explosion when the bags of waste paper the men have been collecting blow up and scatter all over the stage: Substance now, waste no longer. This explosion coincided with a dramatic climax in the music. In a single striking image, the message is that men who have been thrown away by society are not detritus, whether they can fight back or not.

"Coherence", said Chéreau that eveing so long ago, "between ideas, music and drama, is the basis of interpretation". Stagecraft is not decoration : it is Gesamtkunstwerk, the drawing-together of different elements into a whole. Audiences often go for shallow productions because they are bright and jokey, but that isn't necessarily "what the composer intended". Warlikowski's production has a bit of everything. His thing for vivid jewel colours against black and white usually works extremely well, though less so in this case. Maybe ROH chose him to please the punters, so they can tell the difference between prisoners, guards and visitors (which, arguably, should be minimal, just as there often isn't much difference in real life). Huge structures dominate, which is a good thing as they suggest overwhelming forces intimidating small figures. It's a rather well-organized prison, probably not too remote, since there are a lot of outsiders here, including blow-up dolls. Presumably these suggest how society dehumanizes women, treating them as objects, which is perfectly valid and connects to the central idea that the men in this prison are "in the house of the dead". ROH wouldn't have dared show real women getting kicked about, and in any case no-one "should" need the details. London punters go berserk over two seconds of tit, glimpsed for a moment in an entirely appropriate context, so they can't be expected to understand that their own sensibilities are not more important than being moved by the suffering of others. The Prostitute (Alison Cook) as symbol, in bright-green hot pants cavorting chastely with the boys. (Or not so chastely, given that she looks 14.) Nothing wrong with that image per se since prostitutes are the "prisoners" of a messed-up world. Chéreau had the Eagle shot, but for a moment we glimpsed its glory. Maybe I missed Warlikowski's Eagle, but perhaps The Prostitute serves a similar function: she gets out alive.

Big names for the parts where older voices work well like Willard W White as Alexandr Petrovič Gorjančikov, Graham Clark as Antonic the Elderly Prisoner. Stefan Margita sang Luka Kuzmič, as he did in the 2007 run as did Peter Hoare, singing Šapkin. Pascal Charbonneau sang an impressive Aljeja. Ladislav Elgr sang Skuratov and Johan Reuter sang Šiškov. Alexander Vassiliev sang The Governor. As always, House regulars like Jeffrey Lloyd Roberts, Grant Doyle and the always-superb Royal Opera House Chorus were good and reliable. Nice dancers, too, writhing and twisting their (very attractive) bodies, expressing what is suggested in the music but which ROH probably needs to censor for fear of punter wrath. This production is not the best, but by no means is it the worst. But there is not a lot you can do with London audiences who can't be bothered to find out about a composer or an opera beforehand and insist on kitsch and circus. Inevitably that means compromise, which is not good for art.

Monday, 29 January 2018

Eclectic Gamelan Debussy and Boulez - François-Xavier Roth, Paris

François-Xavier Roth was today awarded the Legion d'Honneur for his services to culture. Congratulations, and well deserved cheers ! Yesterday afternoon, he conducted another brilliantly eclectic programme with Les Siècles, at the Philharmonie de Paris screened live, bringing out the connections between Javanese gamelan, Debussy and Pierre Boulez. Unusual, but extremely rewarding, so please make time to listen (archived on arte.tv and also on the Philharmonie de Paris website) because this concert has been put together with insight and great musical understanding. The roots of modern music lie deep in the past, and in forms beyond the western European core.

After Boulez, Debussy Three Nocturnes and La Mer, again connecting old and new. Last Thursday Roth conducted the Nocturnes at the Barbican, London, with the London Symphony Orchestra. Please read what I wrote about that, and its modernism, here. With Les Siècles and Les Cris de Paris at the Philharmonie de Paris, the Nocturnes sounded even more refined and sophisticated, sensitive as this orchestra is to the finest nuances of timbre. a very different sound, but exquisite. My imagination blossomed, thinking back to Asia and dreams of new horizons. Two very different Nocturnes in four days - what a treat ! Roth will be conducting La Mer with the LSO in a few weeks. He's done it numerous times but it never hurts to hear it again, and again. For an encore the fanfare that concludes Debussy's Première Suite d'Orchestre premiered in its new performing edition by Les Siècles in 2012. Please read about that HERE.

Friday, 27 January 2017

Henry-Louis de La Grange, a heartfelt personal tribute

| |

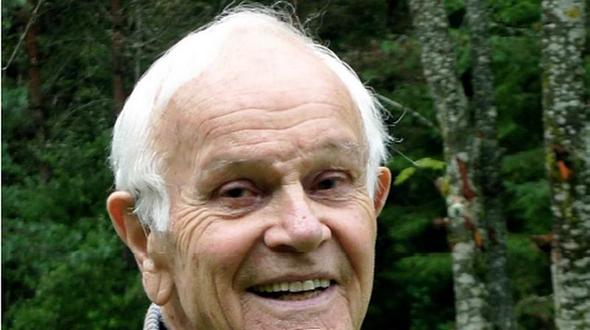

| Henry-Louis de La Grange (26 May 1924 - 27 January 2017) |

HLG's father, Amaury de La Grange, was an early aviator and later a Senator who campaigned for aeronautical innovation. He was a minister in the French government in 1940, detained by the invading Nazis until 1945. HLG's mother, Emily Sloane, was an American heiress, who threw herself passionately into the artistic milieu of early 20th century Paris. HLG had a photograph of a toddler in a sailor suit, hidden behind coats behind his bedroom door. "Man Ray", he said, "my mother commissioned this when Man Ray was unknown and penniless." The kid in the photo was HLG himself. The family's chateau in the Nord was appropriately bequeathed by HLG's father, becoming in 1962 a pilot training school named after Amaury: the family believed in noblesse oblige, the idea that a person's true worth depends on how life is lived. Returning to Paris after the war, HLG studied with Alfred Cortot (and became Cortot's executor). His Damascus moment, however, was hearing Mahler's Symphony no 9. From then on, Mahler, though not to the exclusion of other pursuits. Forty year later, the Mediatheque Musicale Mahler acquired the manuscript of the symphony. It was kept in an underground storeroom, behind many iron security doors. A few of us were invited to view it. Everyone wanted to have a close look, but I held back. My reward was being above to see HLG's face light up with unalloyed bliss as the volume was brought out and the pages opened.

HLG was a gregarious man, who made everyone feel special: that was part of his charm. But he was also a very private person, who didn't reveal himself easily. On HLG's 80th birthday, he was in his living room when his secretary, Anne, came in.with a phone. "I don't take calls here," he said. "You will take this one," she said. "It's Elliott". Elliott Carter. Next thing a jovial voice came from the other end of the line: "How are you doing, young man!" Some years later, HLG wanted me to meet Elliott Carter so he wrote a letter of introduction, in the old fashioned way. Carter was surrounded by BBC big wigs etc. but he pushed them aside and kissed me heartily. "Any friend of HLG is a friend of mine!" A whole world of graciousness that seems lost today.

Although HLG was a celebrity, there were only 100 people at his 80th birthday party, not at all a big public bash, and these included his personal staff, including his cook. Guest of honour was Pierre Boulez. They'd been close friends since the late 1940's even before Domaine Musicale days. Boulez's Mahler came direct from source, long before HLG's books were published, long before Boulez's recordings were made. Neither man was given to surface appearances: both had that French thing for white-hot intellectual intensity, a trait which Mahler himself seems to have had too, even though he wasn't French. Incidentally, it was at that party, over Le Chatelet. overlooking the Seine, where I caught an equally private side of Boulez. A difficult piece had been commissioned for the occasion, which required great technique. Afterwards, the young musician and I were chatting, half hidden in an alcove. Who should pop up but Boulez, making a point of congratulating the young player and offering encouragement. No one else was there, but the player and me, we'll never forget.

So much more, but HLG was so private. But I owe him. Without his kindness and support I would not be doing what I'm doing today, in several ways. He was a father figure to me and a mentor. Sometime back, I was invited to the Paris launch of Jason Starr's film For the Love of Mahler . I couldn't go and the DVD didn't play region 2. But a dear friend got it for me, and I wept. It's a wonderfully moving portrait of HLG, exactly as he was, someone so unique that there'll never be anyone like him again.

Sunday, 4 September 2016

Boulez Bartok Carter Prom 65 Ensemble Intercontemporain

My companion attended some of Boulez's first Proms in 1965 and 1966 (including the UK premiere of Éclat on 2 September 1966), and still keeps the original programme booklets. So Prom 65: Bartók, Carter and Boulez with Baldur Brönnimann, Ensemble Intercontemporain and the BBC Singers was a special occasion. An atmospheric Prom, the lights in the Royal Albert Hall dimmed in darkness, spotlighting the music, and the musicians. As things should be! For music is what some of us care about above all else, however media opinion might differ. Late night Proms have a unique atmosphere, drawing out audiences who care enough about what they listen to that they'd gladly stick around til after midnight and miss the last bus or train home to be there. Besides, smaller-scale music like this needs to be heard in surroundings more conducive to thoughtful listening than in mass-rally conditions.

Baldur Brönnimann and Ensemble Intercontemporain are, fortunately, regular enough visitors to London that they feel like family. They all knew Boulez, personally, too, a factor which added extra poignancy, but the high standards of these performances proved that his legacy lives on.

Bartók's Three Village Scenes (1926) at the beginning, for good reason. Modern music isn't an aberration that began with Boulez, as some think these days, evidently unaware of Schoenberg, Debussy, Stravinsky, Ravel and many others. What all these "modernists" have in common is an affinity for approaches other than that of the late 19th century Austro-German tradition. Bartók's immersion in Hungarian folk idiom helped him find his unique voice. His avant garde expressiveness stemmed from far deeper roots. In Three Village Scenes, the BBC Singers sang with crisp articulation. I have no idea whether their diction was properly Hungarian or not, and don't care. What mattered was the sharpness of intonation, a group of individual voices operating as a tight unit. The orchestra came into focus in the second movement, Ukoliebavka, where a single voice intones a plaintive lullaby. Here, Bartók's individuality - and modernity - palpably present in the shifting, tonally ambiguous forces swirling round her voice. In Tanec mladencov, the sound of ancient instruments was invoked in new form. Vigorous rhythms, jerky angular lines, vibrant energy.

And so to Boulez Anthèmes 2 with Jeanne-Marie Conquer, the soloist par excellence in this piece which she has made her own, having performed it so many times, conducted by Boulez himself.. Although Boulez founded IRCAM enabling whole new generations of composers to explore the possibilities of microtonality and more, Anthèmes 2 is one of the relatively few pieces he wrote that incorporates electronic sound. I heard Boulez and Conquer do this piece live at Aldeburgh in 2010 at The Maltings, Snape, so was particularly keen to hear how the dynamic changed. Unsurprisngly it worked better, since the electronics bounced over the cavernous acoustic of the Royal Albert Hall, the sound stretching for much greater distances than they ever could in the small, boxlike Maltings. Although the electronic effects are created by technology, the sound is "played" by human beings. The sound desk people are musicians responding to the violin, adapting and adjusting.

Anthèmes 2 is a dialogue on many different levels. Boulez said that, as a child, he was fascinated by the call and response of the Catholic Mass, by the use of archaic language and by the sense of ancient times co-existing with the present. As Conquer played, the sound of her violin projected into the vast expanse of the RAH, enhanced so that it seemed to reach out to the upper galleries, and into the dome, deflecting back to the platform, the sound then taken up and transformed by the electronics. Since each of the six sections are so varied, getting this dynamic flow was quite some achievement. Magical, a haunting experience with profound emotional impact.

Anthèmes 2 is a dialogue on many different levels. Boulez said that, as a child, he was fascinated by the call and response of the Catholic Mass, by the use of archaic language and by the sense of ancient times co-existing with the present. As Conquer played, the sound of her violin projected into the vast expanse of the RAH, enhanced so that it seemed to reach out to the upper galleries, and into the dome, deflecting back to the platform, the sound then taken up and transformed by the electronics. Since each of the six sections are so varied, getting this dynamic flow was quite some achievement. Magical, a haunting experience with profound emotional impact.More "dialogue", with Elliott Carter's Penthode (1984-5) since Boulez and Carter were extremely close friends, bouncing symbiotically off one another. Carter constructed Penthode like a mathematical theorem, employing five groups of four instruments, in unusual combinations, like bassoon, piano, percussion and viola. The cells thus interact with each other to form the "orchestra". The piece is thus both a deconstruction of the idea of an orchestra yet also a reworking of the fundamental idea of playing in harmony, without the actual use of harmony. Brönnimann and Ensemble Intercontemporain make Penthode sound easy, though it's not. Players have to listen acutely to one another, each a soloist in his and her own right. No going with the flow and hiding behind a large group, as can happen in lesser ensembles.

In his poetry, E E Cummings defied conventional concepts of language: words deconstruct into fragments, and meaning comes from the visual impression of text across the page. Blank areas "speak", an idea that translates well into music. Thus the very configuration of the forces Boulez employs in Cummings ist der Dichter : a small chorus, but one divided into 16 parts, the BBC Singers making the music flow across the line in the way that Cummings uses single characters of the alphabet sliding over the page. Lines elide, the orchestral lines stretching in arching swathes and oscillating flurries. "Birds here, inventing air", Cummings writes in his bizarre, inventive way, making you pay attention and observe. "Pay attention and observe", a mantra which could also apply to Boulez. Do we hear in this music the movement of birds, as we might in Messiaen ? I don't know, or care, because the experience of being alert and acutely sensitive to nuance is even more fundamental.

Listen to the re-broadcast here. The commentary is vacuous cliché, but the interviews, with members of the ensemble and singers, are enlightening.

Bottom two photos: Roger Thomas

Saturday, 3 September 2016

Mahler Symphony no 7 Rattle Berlin Philharmonic Boulez Prom

Sir Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in Prom 64 at the Royal Albert Hall. Mahler Symphony no 7 and Boulez Éclat (1965) a musically judicious pairing that enhances both works. But first the newsworthy bit! Lines round the block at the Royal Albert Hall, the hottest ticket in town. . Rattle is a National Treasure, as the Japanese honour people who've changed the world around them. Rattle transformed the CBSO and galvanized British music as a whole. He championed music we now take for granted as mainstream, but wasn't 35 years ago. He's an amazing communicator, his enthusiasm motivated by love. As Claudio Abbado said "What drives me is the love of my job, and the passion for things I find inspiring, when I get a chance to immerse myself , to deepen my knowledge of a score, or a book.......if I can deepen that knowledge, I will always do so... the starting point is always love". Very different conductors, but the same basic motivation, one which uncreative minds often do not comprehend.

The equivocal nature of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony makes interpretation elusive. Clues are embedded in the orchestration, so for listeners, as well as for performers, it's a test of sensitivity and musical nous. If a "symphony contains the world", why not? This isn't a piece where “received wisdom” has any place. The tuba calls, then the winds and smaller brass, and the symphony gets underway with the figures inspired by the sound of oars rowing across a lake. Stillness, yet also a sense of purposeful forward thrust. Though there are chords which scream turbulence, the mood is "risoluto", resolutely unperturbed. Here, the finesse of the Berlin Philharmonic paid dividends. It takes skill to hold a coherent line and shape it so well. When the tuba returned, strings glistening around it, I felt as if the symphony was somehow expressing movement in time, past, present and future seamlessly together. Hence the silvery trumpets calling us forwards.

The famous horn call with which the first Nachtmusik begins was suitably expansive, but I was fascinated, too, by the way the Berliners can do subtle detail: quiet bowing and plucking, suggesting mystery, images half-heard, half felt as if hidden in darkness. At night, the subconscious is released and thoughts run free. Hence the Scherzo, often described as a nightmare parody of a waltz. Rattle and the Berliners don't need to scream out "spooks". Instead a quiet violin suggesting a quirky loner, but not a madman, since the part is too integrated to represent selfish ego.

An important insight, since the very structure of this symphony suggests equanimity not psychosis. The two Nachtmusiks surround the Scherzo, like oars around a boat, firmly keep it afloat, reaffirming the sense of duality in the symphony throughout. In the second Nachtmusik, the concept is furthered by the pairing of mandolin and guitar, referring to troubadours serenading lovers, possibly unseen in the night. In many ways, this gentle movement is the human heart of the symphony and the clue to the real soul of Mahler, so often missed these days by notions that Mahler should be loud and neurotic. Rarely have I heard the final passages on clarinet so well defined, oscillating with haunting magic. Horns and tubas may grab attention, but these tiny, fragile moments are, in this interpretation, the heart of the symphony. When the Rondo Finale bursts forth after this stillness, the contrast is shocking, but that, too, I think, is evidence of the subtlety of Mahler's mind and of the idea of hidden mystery that makes this symphony so intriguing. The sudden switch might be Mahler's way of hiding his sensitivity from the world, much in the way people joke about things that hurt, deflecting attention.

Donald Mitchell wrote of the Rondo-Finale that “the violent, unprepared contrast is akin to parting the curtains in a dark room and finding oneself dazzled by brilliant sunlight”. Perhaps the sudden glare drives away fear, but not, I think, what we've learned from the ambiguities of the night. The brass are back, timpani and percussion pound and the orchestra erupts in full flow. A delicious flourish, then an adamant cutting off.What to make of this miniature at the end of a long(ish) symphony? Is it a wail of thwarted rage, or is it a last, sardonic laugh, suggesting the triumph of life? From what we now know of Mahler the man and composer, I'm inclined to go with Rattle's life-affirming confidence.

And back to Boulez Éclat with which the programme began. It uses only 15 instruments, and lasts eleven minutes. Not actually so very different from Mahler, who used large ensembles but created music of chamber-like clarity. Furthermore, Boulez employs guitar and mandolin, just as Mahler did, with piano, celeste, and vibraphone. For me, the connection between the two pieces lies also in the way they explore ambiguities and planes of sound, turning suddenly as if the music itself were a living organism. Éclat shimmers with beautiful lines,bell-like oscillations suggesting purity and freshness, the lines always alert to transformative change. It's mysterious, too, exploring its way through sound. Boulez learned, from Messaien, how to observe quietly, without rushing to impose judgement. In Éclat, we can sense thoughtful observation, as if Boulez were drawing his ideas from watching the movement of birds. An immensely delicate piece, but with parallels to the contemplative passages in Mahler 7 and its mood of secret mystery.

I first heard Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic do this programme in the Philharmonie, where the acoustic is better than in the Royal Albert Hall, even if the Proms atmosphere is more electric. At the Prom, the final movement had maximum impact, so devastating it might have lifted the roof. If the more subtle detail (like the clarinet at the end of Nachtmusik II), was lost, no-one's going to forget that Finale! A friend sent me a video of the applause, shot from way above the stage. Six thousand people clapping and stomping their feet in unison. Later, I listened again and caught Rattle's short interview about the connections between Éclat and Mahler 7th. Very revealing, perceptive, and definitely worth hearing.

Please also read :

Poetic Thoughts : Mahler Symphony no 8 Chailly, Lucerne Festival

Spiritual Mahler 3 Haitink Proms

Blazingly relevant : Mahler 1 Salonen Proms

Tuesday, 10 May 2016

Berlioz Roméo et Juliette - Boulez

In Berlioz's own time, he was very much avant garde. His Grand Treatise on Orchestration (1843) championed among other things the saxophone, invented only three years before and still very much experimental. The picture above shows Berlioz conducting to the horror of his audience, the figures in the foreground supposedly include Franz Liszt. Recently a friend recommended listening to Pierre Boulez's Roméo et Juliette, with the Cleveland Orchestra, recorded live in 1970, though not issued until some years later. How distinctive it sounds ! Boulez wasn't conducting a period orchestra but he seems to have understood why Berlioz used instruments like the ophicleide. They aren't timid ! Hence the fanfare in the introduction, the quirky trumpets and bassoons. the lushness of the harps and above all the sassy punch of the strings, pulling everything together with dramatic forward thrust. We hear the wayward dance figures, and the sinister, almost demonic undercurrents. Roméo et Juliette is neither a stage play nor conventional opera but an innovation: music theatre for orchestra.

Shakespeare carried no cultural baggage for continental European audiences in Berlioz's time, so the composer could do pretty much his own take on the story, using the Garrick version of the play brought to Paris in 1827 by Charles Kemble, which Berlioz attended and where he became infatuated with Harriet Smithson. The picture at left shows Smithson and Kemble in a production in the 1840's. In an age before close-ups and amplification, theatre practice would have to have been more exaggerated than we're used to now. Perhaps Berlioz, a theatre critic, intuited that good orchestral writing had the potential to express feelings in greater complexity than most actors at the time were capable of. The extremes in this music reflect stage practice, yet modified by the sophistication that orchestral subtlety can provide. This is an intense performance, made all the more powerful because Boulez draws from the dramatic tension inherent in the music itself : a composer's insight into interpretation, that springs from within.

Berlioz's Roméo et Juliette isn't about the lovers so much but about cross-currents : feuding families, crowds versus individuals, beauty versus violence and in the midst of all this, an element of supernatural magic that is more "Gothic" than Shakespeare. Structurally it's tight, the Prince holding forth in the beginning and the brilliant Friar Laurence monologue at the end. Montagues and Capulets rip each other apart, but Friar Laurence's intelligence and humanity give Berlioz's Roméo et Juliette its power.

Monday, 21 March 2016

Both innovators - Harnoncourt and Boulez

To appreciate the links between Boulez and Harnoncourt, we need to escape the straitjackets of terminology and focus instead on the deeper philosophy that motivated both conductors.

Both began their careers in an era when technology changed the market for serious music. Within a very short time, the recording industry reshaped public perceptions. Music became a standardized "consumer product", where what counted was how things were sold. Any product designed for the mass market has to appeal to the maximum possible audience. This changes the balance from creative development to "what the buyer expects". Not the same thing.

Harnoncourt reacted against this by rethinking instruments and the physicality of sound. Historically informed practice gets a bad reputation because many assume that it's fetish. But as someone said, "We don't eat baroque food". We can't be as baroque people were, so perfect authenticity just isn't possible. But we can rethink and learn. It's a myth that smaller ensembles are somehow "weaker". Consider the audacity and adventure of the Renaissance, of the Age of Discoveries, of the Reformation and Counter-Reformastion, and of Louis XIV, whose vision wasn't fettered by petty concerns. The dominance of 19th century industrial-era values are not the only way to go. In fact, the Romantic Revolution and the changes that followed was far more radical than some realize. History doesn't stay frozen. Neither Harnoncourt nor Boulez were rebelling per se, but processing the concepts of innovation that have always been behind genuine creativity. It's significant that both Harnoncourt and Boulez were hated by some in their profession precisely because they didn't play the game.Hence the nasty myths that circulate about them being "dangerous".

Ironically, the use of period instruments is a red herring. It's not so much what you're playing with, as why. What really counts is fidelity to the composer and what might have been behind his work. Modern music played on modern instruments reflects this fundamental fidelity.

Coming of age during the war, when performances were limited, and recordings relatively rare, Boulez went back to source, learning directly from scores. Like Harnoncourt, he was thinking afresh. The silly myths about him as demon do not tally with reality. He was exceptionally erudite, with a strong grounding in philosophy, literature and music history and knew the music of the past, even if he didn't conduct or record much. It was enough for him that others were doing that. Intellectually inquisitive, he liked exploring fairly uncharted territory, hence his fascination with Debussy, Schoenberg, Stravinsky and the twentieth century. Hans Rosbaud knew what he was doing when he persuaded Boulez to start a second career as conductor. Boulez saw himself primarily as a composer, and said that shaped the way he conducted. Because he had such respect , he was not an "interventionist" nor imposing his ego. All performance involves interpretation, but interpretation should be based on reasoned understanding. Boulez's passions were white hot, all the more intense because he didn't do things for show.

What Harnoncourt and Boulez had in common was a fundamental respect for music, and for the composers they conducted. Both had uncompromising integrity. Neither courted the popular market. To them, the idea of music as "consumer product" was anathema. Instead they cultivated excellence, pursuing the highest possible standards. It's not for nothing both created their own orchestras, amd frequently worked with smaller ensembles where every individual musician was part of the creative process. And they weren't alone. Think Claudio Abbado, with whom Boulez worked closely, and of William Christie, who shared Harnoncourt's values but with a very different style. Strong personalities with distinctive styles but not corporate market-driven egotists. Perhaps that's why there's such variety in modern European music. Maybe not as much as could be, since ultimately the business has to deal with economic and social realities. But without people like Harnoncourt, Boulez and those with their lively, open minds, we'd be a whole lot worse off.

Pleaseuse the labels below to read my numerous posts on Harnoncourt, Boulez , baroque and modern music

Monday, 14 March 2016

FX Roth Luciano Berio Sinfonia

Berio's Sinfonia was written in 1968, one of those watershed years in history, like 1848, when the world seems to undergo a massive sea change even if the results aren't clear for a while. 1968 was also a pivotal year for music. I remember reading about The Raft of the Medusa, (read more |HERE) not yet realizing who Henze was - I was just a kid - but aware it was something I had to find out about.

Berio's Sinfonia symbolizes so much of what 1968 meant - openness and the will to explore, a sense of endless possibilities, and an awareness that our perceptions of life are shaped by complex and multipole networks of human experience.

Berio describes the Sinfonia as an "internal monologue" which makes a "harmonic journey". It flows, like a river, bringing in its wake the streams and springs which have enriched it, adapting them and changing them, surging ever forwards towards the freedom of the ocean. It's filled with subtle references to many things: to Cythera, one of the cradles of Greek civilization and the home of the goddess of regeneration. Sinfonia is truly a "symphony that contains the world" but it is by no means just collage. It's so original that it rewards active, thoughtful listening.

Quotes from Mahler's Symphony no 2 run through the Sinfonia, like a river, sometimes in full flow, sometimes underground. Mahler 2 is called the "Resurrection" because it's based on the idea that death isn't an end but a stage on a journey to eternal life. There are quotes from at least 15 other cpmposers, but specially significant are references to Don, the first movement of Boulez's Pli selon Pli ( which means fold upon fold, ie, endless layers and permutations). (Read more HERE) Don means gift, so this is like a gift from one composer to another. What has gone before shapes what is to come, but absolutely central is the idea that creativity never ends, but is reborn anew. Stagnation is death. Incidentally one of the best recordings of the Sinfonia was conducted by Boulez, who relished its audacity.

"For the unexpected is always upon us" illuminates the deliberately obscurantist miasma of the text, partly based on Samuel Beckett, though there are also phrases from Claude Lévi-Strauss, the anthropologist of myth. The style is often almost conversational. so you're drawn into what's being spoken, only to be confronted by something elusively confusing. You navigate, as on the rapids of a river, by paying attention and being intuitive, Once I heard an apparently true anecdote about someone who built a machine that could write music. Along came Berio, who twiddled a few knobs and buttons and created something genuinely original. The machine's inventor was not pleased. That's the difference between real art and fake.

Berio had a quiet sense of humour. When he quotes Mahler's Des Antonius von Paduas Fischpredikt (read more here) , he knows the fish don't understand and will keep fighting. Perhaps Berio knew that some folk would never "get" Sinfonia, but he wasn't bothered as he didn't need to prove anything. Traditionally -- if that's a word which can apply to someone as lively as Berio -- the texts have been semi-spoken at odd pitches, using tuning forks and impossibly clipped British accents, which adds to the sense of quixotic unreality. At the end, the performers name and thank each other -- reality playing tricks with art.

Berio's Sinfonia connects, too, to many other works of the period, such as Stockhausen's Hymnen (read more HERE) and to Bernd Alois Zimmermann's Requiem for a Young Poet (Read more here). All three pieces "open windows" in different ways onto other aspects of life, culture, history, literature and music. All attempt a creative and original synthesis of human existence. Not easy goals to achieve. Indeed, I'm not sure that music like that can be written today in times where so many prize insularity and fear diversity. François-Xavier Roth strikes me as an ideal Sinfonia conductor because his background lies in the adventurousness of the baroque, which has animated his passion for the avant garde. (Read more HERE) Feview of the second concert coming soon.

Wednesday, 27 January 2016

Hommage à Pierre Boulez, Philharmonie de Paris

Hommage à Pierre Boulez at the Philharmonie in Paris, live last night, now online HERE. Though there are live performances, this is much more than a concert. There are readings from Boulez's writing, not only on music but on philosophy and the arts in general. Boulez was a natural communicator: someone who read many of his works, not only the books but articles, etc, said that Boulez was a true intellectual, a man whose mind ranged over many disciplines, always analysing, questioning and developing original perspectives. We know Boulez the composer, the conductor, the teacher, the arts policy visionary, but Boulez as thinker is yet to be fully appreciated. There's even a reading from one of his books on Paul Klee, whose work Boulez collected. Think about it. In Klee's paintings cells multiply in myriad shades and hues forming patterns and layers of colour and light. From The Impressionists to Debussy, from Klee to Boulez.....

There are also clips from the archives: interviews in which Boulez talks about Messiaen, René Char and others. At 1.26, a joyous masterclass which shows how Boulez interacted with people on a personal level. That's exactly what he was like, totally sincere and down to earth. At a private party in Paris a few years ago, there was a performance of a difficult new work which required extreme technique from the soloist, who was very young. Imagine how he must have felt, playing in front of an auience of less than 100, with Boulez as guest of honour in the front row. Later, I chatted with the young player in a curtained alcove off the main room. Then along comes Boulez, and quietly congratulates the young player, encouraging him and giving support. No witnesses, no cameras: total sincerity. After that you could have scraped the player off the floor.

What comes over well in this tribute is a very palpable sense of personal loss. Most of the people here knew Boulez in some personal capacity. Not for them the nasty myths so many seem compelled to repeat. Thousands may want to believe the world was created in exactly 7 days, but that doesn't make it true. Indeed, the hate directed at Boulez is a measure of his genius. Mediocrity can't cope with true originality.

If the film is choppy, I think that reflects what the experience must have been like live. There would have been gaps in the performance to change the stage and show the video clips. But notice - no talking heads, no "experts". Boulez himself speaks ,through his own words and music.

Thursday, 14 January 2016

Boulez, Birtwistle and Max - the famed Boulez at 80 concert

Now available on BBC I player, the famous concert "Boulez at 80" where Boulez, Harrison Birtwistle and Peter Maxwell Davies all met together on stage at the Barbican, London, when Boulez was presented with a medal from the British Association of Composers. Birtwistle spoke of how he had, as a young man, seen Boulez’s score for Le marteau sans maître. He’d seen nothing like it before, and it became his “rite of passage” musically. Boulez was an “immaculately uncompromising” composer and conductor whose example showed the paucity of populist, surface-level music. “A concert hall is not a museum”, he added, for music like Boulez’s “propels us into the future”. Then Boulez, humbly and simply, went back to work.

Boulez and Birtwistle go way back: Boulez's recordings of Birtwistle, like Theseus Games, are the absolute benchmarks. Birtwistle and Maxwell Davies go back a long way too but for decades they weren't on the best of terms, though, subsequently, the huge revival of interest in Birtwistle has brought Max into the spotlight, too.

This film is also important for the interview at 53 minutes in where Boulez explodes some of the myths said about him (direct link here). He explains the context of the story about blowing up opera houses. This came from his frustration at the way opera houses were managed, where a conductor didn't know who the orchestral players or evern the cast might be. As he says, Mahler said much the same thing, and so does Christoph von Dohnanyi (more HERE). He also explains the famous quote "I sleep faster", which was a bon mot about how he managed to cram so much into his days. He didn't sleep 2 hours a night! On ideologies "You have to find your discipline in order to break it. If you are constantly constrained by your discipline you become sterile. Ideologies are very interesting, at one point, when they are forging something, but when they are not forging something, when they are empty, then that is detrimental to your capacity of inventing" It's pertinent that Boulez's own music soon went way beyond serialism, in no small part due to John Cage's ideas on chance. Boulez likes modertn music but that's not "ideology". There are composers obsessed with formula but not him.

Charles Hazlewood talks about discipline in conducting. Maybe because I am a composer", says Boulez, " I think the composer is more important than the performer.. not too much of an ego, simply that. But I try to understand what the composer is tryingb to say, and when you see how carefully he has written a score, then you try to be as careful as he was. So then I'm careful about the balance, the style, the dynamic, the exactitude (which in the French meaning of the word has different connotations to English). On Le soleil des eaux, he speaks of the way he wrote the original before he became estabhished as a conductor, but when he conducted it with the BBC in the early 1960's he could see, from a conductor's perspective , how it could be improved. As to his legacy "I don't care, I won't be around!< he grins. "Each generation takes from its past and goes ahead."

In was at this concert, back in November 2005. Look who else was in the audience ! I'm in frame, too, but a blurred dot. Everyone looks so young. Some are no longer with us. Below my notes then on Le soleil des eaux.

Le soleil des eaux was written in 1948, when Boulez was barely 23. Already, though, it shows his distinctive personality, and still sounds strikingly original some sixty years later. René Char was a surrealist, and a member of the French Resistance. These poems come from a post-war political protest and were published barely a year before Boulez set them. Here attention is on the voice, which leaps up the scale, and turns capriciously, like the goldfinch’s darting movements. Boulez observes nature clearly – Messiaen taught him well. [Elizabeth] Atherton was in her element now, gloriously. The high timbre suited her well and she shaped the languor of the lines. Drama is added with sudden flashes of orchestral interjection, which the vocal part complements. “L’homme fusille”, sings Atherton “cache-toi!” (man is armed, hide!), with emphasis on the urgent “cache-toi!”. The second song, La Sorgue, Chanson pour Yvonne, is a much larger work, its powerful imagery condensed into barely five minutes.

The piece starts with a delicate otherworldly weaving of wordless soprano singing, harp and vibraphone. Then the orchestra and large chorus surge in, with the power of a mighty river unleashed. The choral writing is so finely textured that individual voices spread across the spectrum. The idea isn’t that specific words should stand out, but rather the impressionistic effect of multi-layered sound. This really is vocal writing as instrumental, where the total image matters. It’s emphasised by the regular cries of “Rivière!” when the choir pulls as one, before relaunching into the flow. Also reversed is the conventional role of soloist: the soprano’s contribution is to soar over and around the massed voices, singing a line that is literally “beyond” words. Boulez chose this piece, seldom performed live because of its personnel demands, as his own tribute to the BBC Symphony and Singers, who have made it one of their specialities."

Tuesday, 12 January 2016

Boulez Mass

Announced in the French press: "Un hommage sera rendu jeudi à 16H00 en l'église Saint-Sulpice à Paris au compositeur et chef d'orchestre français Pierre Boulez, décédé mardi dernier à 90 ans à Baden-Baden en Allemagne, a annoncé lundi sa famille."

Below, a clip from Messiaen's Le Banquet celeste, played by the chief organist Marcel Dupré, a contemporary of the composer. I don't know whether there will be a full Mass or a memorial, but I suspect it will be a Mass, and it's a good place to remember StTrinité is smaller and won'tfir enough people. Pierre Boulez. Please see my post on the relationship between Messiaen and Boulez, and the church of Sainte Trinité.

St. Sulpice Paris Pipe Organ Dupré Plays Messiaen by DeliaStephens

Saturday, 9 January 2016

Boulez Mahler 2, informed by Messiaen

Pierre Boulez stands, in silence, after the conclusion of his Mahler Symphony no 2 at the Philharmonie, Berlin, in 2005. Look at Boulez's expression. The music hasn't ended simply because the notes have faded away. the symphony ends gloriously but victory hasn't been reached without struggle. Der Mensch liegt in größter Not! Der r Mensch liegt in größter Pein! Not even angels can turn the soul away from God. Boulez's approach in this performance, with the Staatskapelle Berlin, is steely, craggy and utterly determined. He understands the significance of the first movement and the stages through which the soul goes on its journey. A quiet but intense reading, absolutely true to the composer and to his work as a whole entity.

Today, listening after Boulez's own death this week, what struck me is the relationship this performance has to Messiaen's Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum. Mahler isn't writing about the death of one man but about mankind's search for meaning. Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum refers to the End of Time, when an angel shall sound a trumpet asnd the earth will be rent asunder. Cataclysmic stuff, bringing from Messiaen music that's almost geological in its cragginess - no strings, only percussion and winds, Boulez's interpretation is informed by his knowledge of Messiaen and perhaps, too, by his own formidable knowledge of music history. When the trombones blast, and the distant trumpets are heard, we think of the Angel of the Book of Revelation, as Mahler almost certainly did, and when we hear the piccolo details, we can figure better what they might mean. Obviously my appreciation of this performance is informed by my fascination with Messiaen and with Et Exspecto resurrectionum mortuorum and the Quartet for The End of Time. Read some of what I've written before HERE and HERE.and much more.

But my response is also affected by thinking so much this week about Boulez and Messiaen. They had a bond like father and son, which ran even deeper than many real-life father and son relationships. A few years ago, someone made a snide, nasty remark about Boulez disliking Turangalîla-and falling out temporarily with Messaien. It was the usual silly notion of Boulez as demon. Pierre-Laurent Aimard was present and hit the roof. Aimard, who was Messiaen's "second son", said he'd heard about it direct from Messiaen himself. Since when do fathers and sons always agree? Messiaen used the term Tuer le père which simply means that you can't grow up unless you stand on your own feet. Messiaen knew Boulez's abilities and wouldn't have dreamed of holding him back. The scrap didn't last. Soon after, Boulez heard that Messiaen was looking for a balofon. Messiaen found one and carried it, as a surprise, up to the organ loft at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité where Messaien played every day. Messiaen was so happy he had tears of joy even when telling Aimard about it years later. Creative minds aren't constrained: copying is a mark of mediocrity. Healthy relationships are not threatened by fear of change. And so Messiaen and Boulez will continue to enlighten us long after they are gone|

Friday, 8 January 2016

Boulez - the last interview

Doubt? The very concept of doubt no longer has meaning these days. For Boulez, culture meant being open to possibilities. All too often, the less someone knows the more certain they are that no-one else can know. That's why Boulez is dangerous. He thinks. I cannot use the past tense for a man so mentally and creatively alive. Boulez didn't suppress anyone who wasn't already suppressed in themselves. Since opinions are controlled by wide market forces, society itself creates suppression. It's nuts to project that resentment onto someone who represents the opposite of groupthink. Doubt is the antidote to mindless assumptions, to demagogue groupthink. No wonder so many defer to supposedly Holy Writ. Doubt and provocation, the engines that drive the eternal quest for wisdom and knowledge, growth and renewal. If that's scary, so then is the whole concept of civilization.

Thursday, 7 January 2016

Pierre Boulez - a personal tribute

Tributes pour in all round for Pierre Boulez, who died on Tuesday after a long illness. So many wonderful tributes - Paul Griffiths (thank goodness) in the New York Times, Le Monde, Roger Nichols in the Guardian, the Telegraph, the LSO, France Musique and many others - more to come, no doubt. These are the best informed.

There's also an all day broadcast from France Musique, video of Répons with Ensemble Intercontemporain on arte.tv, and a selection of videos on medici.tv.

So what I'll add is something you won't get anywhere else - personal, first-hand memories.

I was at the last concert in the Pli selon pli tour with Ensemble Intercontemporain in 2011 at the Royal Festival Hall. Boulez looked fragile, ashen: I thought he was exhausted after doing 20 concerts in the space of a month. He kept changing his glasses, and finally gave up, conducting by instinct. He knew each of those musicians well enough that he could hear them, and they knew him well enough that they could figure out what he wanted. If, at times, the performance seemed tentative, it was extremely moving because we could feel the rapport betwenn conductor and orchestra . That night I stood outside in the rain, waiting as the players went back to their hotels, or for dinner. Boulez didn't show but I was glad because I thought he needed a rest. As it turned out, that was the last concert he ever conducted. I much preferred the original recording with Christine Schafer, whose voice was more ethereal and magical, but I'm so glad I was there. Read more here.

In Berlin in 2007, Boulez conducted Mahler Symphony no 8 at the Philharmonie (my review here), a powerful performance that really brought out the meaning of the many references to light and enlightenment. Accende lumen sensibus! The difference between a good conductor and a very, very good conductor is that he can access meaning.. Here's what i wrote in 2009. It was such a performance that its memory will live with me forever.

At Aldeburgh, Boulez was giving a masterclass on Incises for Piano, Sonatina for Flute and Piano when a busload of daytrippers popped in. They'd come for the Bach Masss later that evening but for some reason had arrived hours too early, so they sat in on Boulez. To welcome them, he chatted about the early post war years and how hard it was to get hold of musical scores. They could relate to that, since they were mostly his own age. That explained why he was so into the 12 tone system in those years. ,It wasn't "ideology" just something that stimulated him. They'd been so deprived during the war that they were catching up on years of drought. In his youth, Boulez conducted Rameau. He knew his Bach. So the Bach Mass crowd were won over. They stayed for the class and for the performance. They liked the man and were prepared to hear what he had to say. None of that bigoted prejudice we get too much of now.

The most touching moment wasn't public at all. We were at a private party in Paris, where a young clarinettist played a difficult new work that involved a lot of circular breathing and flawless technique. The player was young. It was the biggest gig of his lifetime. Only 100 people in the audience but Boulez was Guest of Honour, seated right in front. Afterwards, I chatted with the young player. We weren't in the main room, but in a kind of alcove off the side. Who should join us? Boulez, who had made time to seek out the young man. "You're good" he told him, and gave him words of encouragement. No-one was present, it was entirely personal and sincere. The player was speechless. I almost had to pick him off the floor.

Boulez was a man of integrity and taste, for whom art was paramount, not self. Of course he was cerebral but what's wrong with that? He was deep. He didn't do "emotional diarrhoea" . So what if others didn't get him, and projected their hang-ups on him ? He was his own person.

Sunday, 3 January 2016

Luciano Berio Sinfonia "For the unexpected is always with us"

Good composers internalize and learn. Cythera in mythology was the home of the goddess of renewal and regeneration. Thus the film starts with shots of a strange primordial-looking landscape out of which arise strains of Mahler’s Symphony no 2, a "Resurrection" in the deepest sense. Berio's Sinfonia is no mere collage but a strikingly original new work that defies conventional ideas of what a symphony "should" be.

Berio describes the Sinfonia as an "internal monologue" which makes a "harmonic journey". It flows, like a river, bringing in its wake the streams and springs which have enriched it, adapting them and changing them, surging ever forwards towards the freedom of the ocean. Like Mahler himself, Berio was cerebral. Berio is seen in his study, surrounded by scores and books, with a model ship on display. Riccardo Chailly, also highly focused and erudite, talks about Stravinsky and Schoenberg, who, in their different ways, progressed the direction of modern music. Composers don't operate in "schools". Schoenberg's great achievement was to opens tonality outwards so others could develop things further. In Sinfonia, there are references to at least 15 different composers, some quite subtle. There's a quotation from Don, the first movement of Boulez's Pli selon Pli (fold upon fold). It's a "gift" from one master to another, both of them fascinated by multi-dimensional levels and perspectives, ever-changing flurries and eddies. Incidentally one of the best recordings of the Sinfonia was conducted by Boulez, who relished the wit.

"For the unexpected is always upon us" as a phrase rings out clearly, illuminating the deliberately obscurantist miasma of the text, partly based on Samuel Beckett, though there are also phrases from

Claude Lévi-Strauss, the anthropologist of myth. The style is often almost conversational. so you're drawn into what's being spoken, only to be confronted by something elusively confusing. You navigate, as on the rapids of a river, by paying attention and being intutitive,. Take nothing for granted: meaning operates on many levels. Once I heard an anecdote about someone who built a formidable machine that could invent music, electronically. Along came Berio, who twiddled a few knobs and buttons and created something genuinely interesting. He made real music by not being too up himself.

Berio had a quiet sense of humour. When he quotes Mahler's Des Antonius von Paduas Fischpredikt (read more here) , he knows the fish don't understand and will keep fighting. Perhaps Berio knew that some folk would never "get" Sinfonia, but so what as long as a few do. Traditionally -- if that's a word which can apply to someone as lively as Berio -- the texts have been semi-spoken at odd pitches, using tuning forks and impossibly clipped British accents, which adds to the sense of quixotic unreality. At the end, the performers name and thank each other -- reality playing tricks with art. No performance of Berio's Sinfonia is ever quite the same, and you get something different each time. "For the unexpected is always upon us".