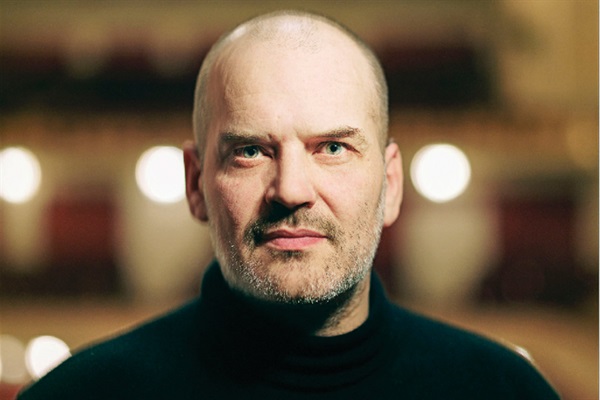

To mark the start of the Wigmore Hall's 2018/19 season, Florian Boesch and Malcolm Martineau in a characteristically thought-provoking programme of songs to poems by Heinrich Heine, by Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt and Robert Franz. From Boesch and Martineau, you can always expect the unexpected, but done with intelligence and insight. So I'll start with the end, and the encore, which Boesch introduced as being like those endless but addictive Brazilian TV soaps where relationships go round and round forever. Robert Schumann's

Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen, standard repertoire, but rarely heard with such originality. Heine's mischevious wit came to life as Boesch sang, his eyebrows arched in disbelief as he counted the different permutations on his fingers.

"

Es ist eine alte Geschichte,

Doch bleibt sie immer neu;

Und wem sie just passieret,

Dem bricht das Herz entzwei".

But back to the beginning of the recital where Boesch and Martineau sang nine songs to poems from Heine's

Lyrisches Intermezzo. Had the point of the programe not been evident beforehand, the songs might have come as a shock, since these weren't the familiar texts to Schumann's

Dichterliebe but settings by Robert Franz (1815-1892). The two men were contemporaries. Schumann praised Franz's first songs while he was a music critic for Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Hearing Franz's settings of the same texts that Schumann set highlights the difference in their compositional styles. In Franz's

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai (op 25/5 1870), the piano part is ornate, suggesting floral imagery, while Schumann's version emphasizes the declaration of love. Schumann responds to the irony in Heine, whereas Franz softens the more sarcastic edges. The strong definition of Schumann's

Im Rhein from

Dichterliebe (op 48, 1848) suggests the power of the river and cathedral, contrasted with "

meines Lenbens Wildnis" : the poet hardly dares speak of lost love. In Franz's version, (op 18/2 1860), "

die Augen, die Lippen, de Wanglein" glow radiantly. The suppressed fear in Schumann's

Allnächtlich in Taume gives way to sadness in Franz. Schumann represents Romanticism with its sense of individualism and the unconscious, while Franz represents Romanticism in more Beidermeier discretion. Franz, like many other composers of the period, such as Carl Loewe or Franz Lachner, and many others, are important because they remind us of the many different seams in the Romantic imagination

Yet another strand of Romanticism, with an intermezzo before the songs of Franz Liszt, Schumann's

Abends im Strand (op 45/3 1840) ; the very image of paintings by Caspar David Friedrich where tiny figures on shore watch ships sailing to unknown places. Ardent figures in the piano part suggest excitement, and the vocal part rises wildly at the phrase "

und quaken und schrei'en" before retreating from adventure to the gentility of the last verse where "

endlich sprach neimand mehr".

Boesch and Martineau continued with Liszt's Heine settings, including

Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam (S309/1 1860),

Du bist wie eine Blume (S287 1843-9). In Liszt's

Im Rhein,

im schönen Strome (S272/1 1840) the piano line depicts the rolling flow of the river, which gradually gives way to more sparkling figures illuminating the last verse which mentions the lost beloved, then ends in reassuring repeated motif. Martineau shone, and Boesch's dignified phrasing added solidity.

The high point in this set was

Loreley (S273/2 1856) in one of the finest performances of this song I can remember. Liszt creates textures in the piano part which suggest the sparkling waters, the word "loreley" embedded wordlessly, over and over. The delicacy with which Martineau played showed why this song is so often performed by women. But Boesch has the skills to carry it off even more convincingly. He sang the first verses with tender restraint, creating a sense of wonder : the protagonist is, after all, not the loreley herself but a mortal wondering why the tale is so tragic. He sang the lines "

die luft ist kühl" so quietly that a ghostly chill seemed to descend, and even negotiated the tricky sudden ascent to higher range on the word "

Abendsonnenschien". Martineau played the second phase of the song to bring out the lyrical, golden warmth with which the loreley seduces. Boesch's voice seemed to glow on the words "

Die schönste Jungfrau sitzet" growing with strength and volume, evoking the power of the "

wundersame, gewaltige Melodie", leading logically into the next section of the song where the seamen are seized "

mit wildem Weh", and hurled to their deaths. Rumbling turmoil in the piano part, Martineau unleashing the fury in the waves, enhancing Boesch's darker timbres as he sang, emphasizing out the menace and horror. This created a wonderful contrast with the last section of the song, where the gentler melody returns, as the river becomes calm once more. Now not only the motif "loreley" repeats but whole phrases, gradually retreating into a serenity which we now know will last only until the next doomed sailor appears.

Boesch and Martineau capped this wonderful Liszt

Loreley with an equally impressive Schumann

Belsazar (op 57, 1840). They have done this song on numerous occasions, but this performance was exceptional, Boesch relishing the inherent drama but doing it with such naturalness that it didn't feel forced. Theatrical as the scene is, Heine's telling of the story is human. Martineau played the rippling figures evoking the high spirits of the party in the palace, the lines flowing like wine. "

Es kirten die Becher, es jauchzten die Knecht" sang Boesch with robust vigour. This matters, for it is drink that makes the King bold enough to curse Jehovah. Boesch's timbre is elegantly regal and his words rang forcefully : "

Ich bin der König von Babylon !" Martineau's piano spakled : a last moment of fizz before the mood descends into hushed fearfulness. A sinister chill enetred Boesch's voice, his words measured and carefully modulated, his "t"'s as sharp as knives. Great insight, for that very night Belsazar gets stabbed to death.

After this immensely rewarding first half of the recital came a selection of Schumann's Heine settings, including

Die beiden Grenadiere (op 49/1 1840). vividly characterized and muscular, and three Lieder from

Myrthen op 25 ,

Die Lotosblume, Was will die einsame Träne and

Du bist wie eine Blume. showing Boesch at his sensitive best.

Trägodie (op 64/3 1841) a song in two contrasting parts. Lover elope in hope, but their dreams are doomed. The songs are neither Heine's nor Schumann's finest, so they depend more than usual on good performance. Boesch and Martineau did them so they felt like real people, rather than maudlin figures as in some less accomplished hands I've heard. Boesch and Martinaeu gave a very good account of

Liederkreis (op 24 1840) with some extremely interesting high points.

Warte, warte wilder Schiffmann suits Boesch's masculine physicality, while

Berg' und Burgen schau'n herunter brought out something even harder to achieve ; exquisite, well-defined nuance, for this is an almost bi-polar song and poem. A boat sails merrily on the sunlit river, but above loom mountains and castles, realms of death and night. "

Oben Lust, im Busen Tückern, Strom du bist der Liebsten Bild!" In comparison,

Mit Myrten und Rosen is full-hearted joy, though it, too, is haunted by a Heine kick in the tail, which Boesch and Martineau brought out with subtlety.

Liederkreis can often be the crowning glory of a recital, and this one was good, but the first half of this programme was so unusual and so brilliantly done that this time, for a change,

Liederkreis took second place.