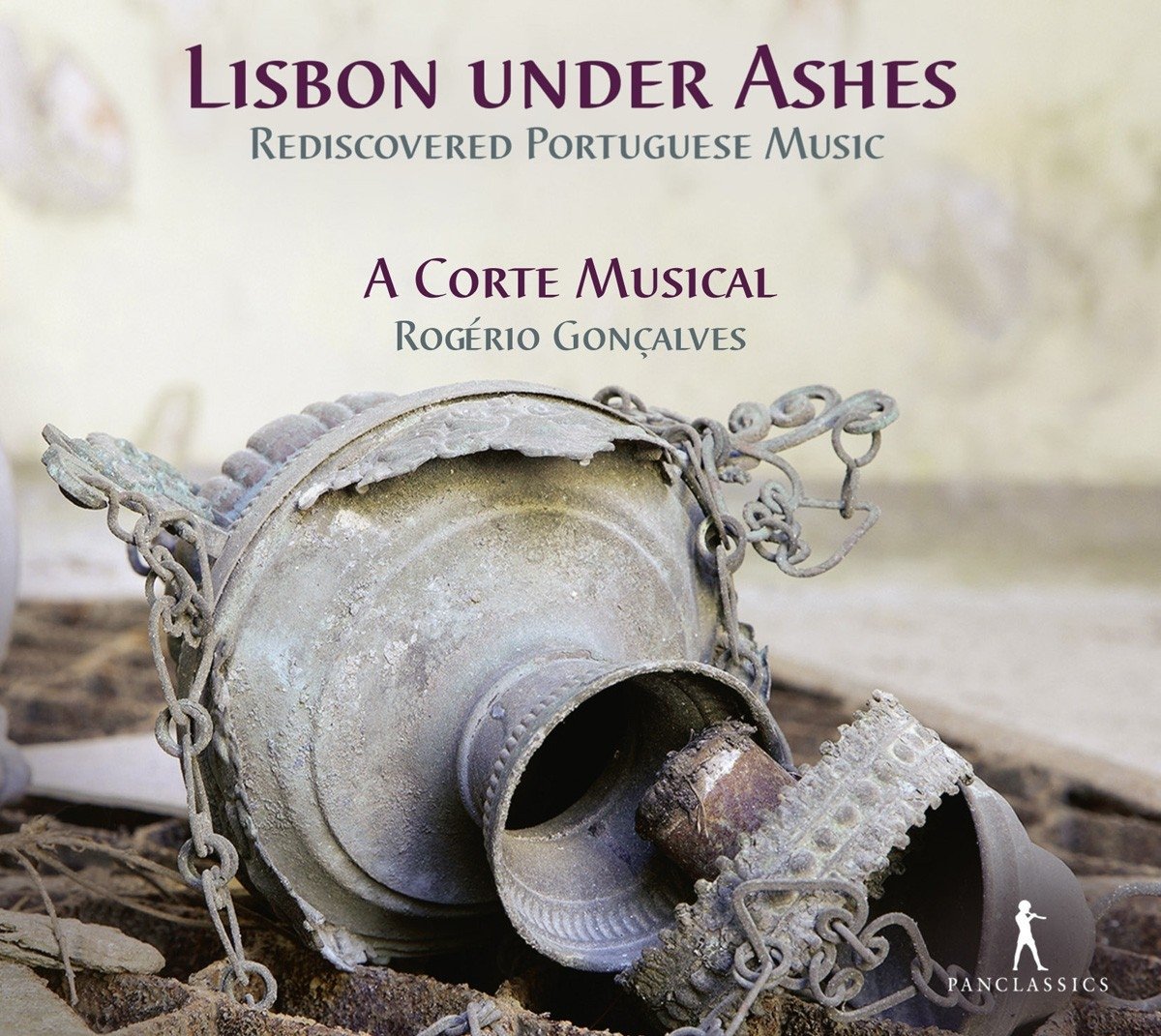

In 1755, Lisbon was destroyed, first by a massive earthquake, then by a tsunami pouring in from the Atlantic, then by fire and civil unrest. The scale of the disaster is almost unimaginable today. The centre of the Portuguese Empire, with treasures from India, Africa, Brazil and beyond, was never to recover. The royal palaces, with their libraries and priceless collections, were annihilated. Some manuscripts survived in other cities, suggesting the scope of the original collections, which went back centuries. This recording, by A Corte Musical, led by Rogério Gonçalves, from Pan Classics, gives us an insight to some of the music that was lost. The spirit of the Age of Discoveries invigorated the Portuguese baroque, stimulating a vibrant culture that almost uniquely embraced influences from all over the world. So lively and varied is this recording that even without the historic significance, it's a delight to listen to.

Toquen as sonajas, by Gaspar Fernandes (1566-1629), was discovered in the Cathedral at Oaxaca, Mexico. Fernandes was an organist working in Guatemala at a time when Portugal and Spain were briefly united under one king. Accompanied by beaten percussion, the song is a round, the voices joining at different points to create lively rhythms. The words are simple : "Play the sonajas, sound the rebecs, and the Portuguese rejoice", repeated in different patterns in three distinct phases. A sonaja is a rattle, and a rebec a bowed string instrument, both known in medieval times, and connected to instruments in the Middle East and Africa.

Olà plimo Bacião, an anonymous piece from a 17th century codex, was found in the monastery of Santa Cruz in Coimbra. It's decidedly not monastic, but a negrillo, a type of villancico inspired by the "zente de Guiné" a term applied to all Africans in the Portuguese orbit. The rhythms suggest dance, possibly of African origin, possibly too uninhibited for the chroegraphy to be preserved, as was apparently the usual case in this period. A lively refrain "Gulungà, gulungà, gulungué, clap your hands, move your feet". An interlude with the gentle plucking of a stringed instrument, introduces a more reflective mood, in which the voice parts describe a beloved child, ie Jesus "for he is our God, and with the the black Santo Thomé, he is our God".

A vosa porte Maria was found in Madrid and Albrorada is an arrangement of a traditional melody from Tuizelo in northern Portugal. The former is plaintive and prayer-like, a soprano leading the chorus of voices and instruments. The latter is a vibrant parlay where the instruments interact, strings and winds over a strong rhythmic foundation. Làgrimas de Anarda is a sonnet by Manuel Botelho de Oliveira (1636-1711) one of the pioneers of Brazilian literature, taken from a book published in Lisbon in 1705. The original music is lost, so here it is used with a French melody of the period. Another interesting combination is the Passacalha da triste vida, an anonymous 16th century villancico paired with a passacaglia from an opera from the time of Monteverdi. The oldest piece in this collection is Toda noite e todo dia, from a songbook compiled in the 16th century , discovered in Elvas in 1928. The text deals with impossible love "Que do que não traz provieto, Lança mão a fantasia" (What does not bring benefit gives way to fantasy) The lovely soprano line elides over jaunty rhythmic strings, and then is joined by the tenor, singing alongside, not in duet. Tramabote is one of the earliest purely instrumental pieces from the Portuguese baroque. Bayle dei amor resucitado is part of a vanished genre of early theatrical pieces with incidental music Cupid is swooning from love, but damsels and handsome young men greet it, and all sing together "The swan which sings from the tomb promises the more from life, the more deceased it is". Also allegorical is Deseos sin esperança (desire without hope) by Frei Filipe Madre de Deus, a Lisbon born vilhuellist who worked in the Spanish court.

In complete contrast Mariniculas to a text by Brazilian poet Gregorio de Matos (1636-1696), published in 1668, which describes a glamorous rascal who makes ladies swoon, but who was "such a flaming faggot, he never looked at bonnets, finding the best undergarmnets in his pants". And more ! "empurrado por umas Sodmas no ano de tantos em cima de mil". Such a text might have stayed hidden in print, but here is used with a gay (in the old sense of the word) melody found in an archive in Coimbra. Another early song, Entre os parasismos graves, entwines male and female voices singing of "saudade infelice" before the cheerfully upbeat Dime pedro, por tu vida by Manuel Correea (1600-1653) from one of the oldest musical codices in Latin America. Wonderfully expressive percussion and jangly rhythms suggest indigenous influence of some kind. The singer is dancing in order to seduce, and presumably succeeds, as she's joined by a tenor. A short, sassy refrain "eh, eh eh !" punctuates the end of each verse. Exuberantly vivid.

A Corte Musical, led by Rogério Gonçalves,who compiled and researched this collection and also plays bassoon and percussion. Tthe singers are Mercedes Hernández and Alice Borciani, with David Sagastume (alto) and Daniel Issa (tenor).

Toquen as sonajas, by Gaspar Fernandes (1566-1629), was discovered in the Cathedral at Oaxaca, Mexico. Fernandes was an organist working in Guatemala at a time when Portugal and Spain were briefly united under one king. Accompanied by beaten percussion, the song is a round, the voices joining at different points to create lively rhythms. The words are simple : "Play the sonajas, sound the rebecs, and the Portuguese rejoice", repeated in different patterns in three distinct phases. A sonaja is a rattle, and a rebec a bowed string instrument, both known in medieval times, and connected to instruments in the Middle East and Africa.

Olà plimo Bacião, an anonymous piece from a 17th century codex, was found in the monastery of Santa Cruz in Coimbra. It's decidedly not monastic, but a negrillo, a type of villancico inspired by the "zente de Guiné" a term applied to all Africans in the Portuguese orbit. The rhythms suggest dance, possibly of African origin, possibly too uninhibited for the chroegraphy to be preserved, as was apparently the usual case in this period. A lively refrain "Gulungà, gulungà, gulungué, clap your hands, move your feet". An interlude with the gentle plucking of a stringed instrument, introduces a more reflective mood, in which the voice parts describe a beloved child, ie Jesus "for he is our God, and with the the black Santo Thomé, he is our God".

A vosa porte Maria was found in Madrid and Albrorada is an arrangement of a traditional melody from Tuizelo in northern Portugal. The former is plaintive and prayer-like, a soprano leading the chorus of voices and instruments. The latter is a vibrant parlay where the instruments interact, strings and winds over a strong rhythmic foundation. Làgrimas de Anarda is a sonnet by Manuel Botelho de Oliveira (1636-1711) one of the pioneers of Brazilian literature, taken from a book published in Lisbon in 1705. The original music is lost, so here it is used with a French melody of the period. Another interesting combination is the Passacalha da triste vida, an anonymous 16th century villancico paired with a passacaglia from an opera from the time of Monteverdi. The oldest piece in this collection is Toda noite e todo dia, from a songbook compiled in the 16th century , discovered in Elvas in 1928. The text deals with impossible love "Que do que não traz provieto, Lança mão a fantasia" (What does not bring benefit gives way to fantasy) The lovely soprano line elides over jaunty rhythmic strings, and then is joined by the tenor, singing alongside, not in duet. Tramabote is one of the earliest purely instrumental pieces from the Portuguese baroque. Bayle dei amor resucitado is part of a vanished genre of early theatrical pieces with incidental music Cupid is swooning from love, but damsels and handsome young men greet it, and all sing together "The swan which sings from the tomb promises the more from life, the more deceased it is". Also allegorical is Deseos sin esperança (desire without hope) by Frei Filipe Madre de Deus, a Lisbon born vilhuellist who worked in the Spanish court.

In complete contrast Mariniculas to a text by Brazilian poet Gregorio de Matos (1636-1696), published in 1668, which describes a glamorous rascal who makes ladies swoon, but who was "such a flaming faggot, he never looked at bonnets, finding the best undergarmnets in his pants". And more ! "empurrado por umas Sodmas no ano de tantos em cima de mil". Such a text might have stayed hidden in print, but here is used with a gay (in the old sense of the word) melody found in an archive in Coimbra. Another early song, Entre os parasismos graves, entwines male and female voices singing of "saudade infelice" before the cheerfully upbeat Dime pedro, por tu vida by Manuel Correea (1600-1653) from one of the oldest musical codices in Latin America. Wonderfully expressive percussion and jangly rhythms suggest indigenous influence of some kind. The singer is dancing in order to seduce, and presumably succeeds, as she's joined by a tenor. A short, sassy refrain "eh, eh eh !" punctuates the end of each verse. Exuberantly vivid.

A Corte Musical, led by Rogério Gonçalves,who compiled and researched this collection and also plays bassoon and percussion. Tthe singers are Mercedes Hernández and Alice Borciani, with David Sagastume (alto) and Daniel Issa (tenor).

No comments:

Post a Comment