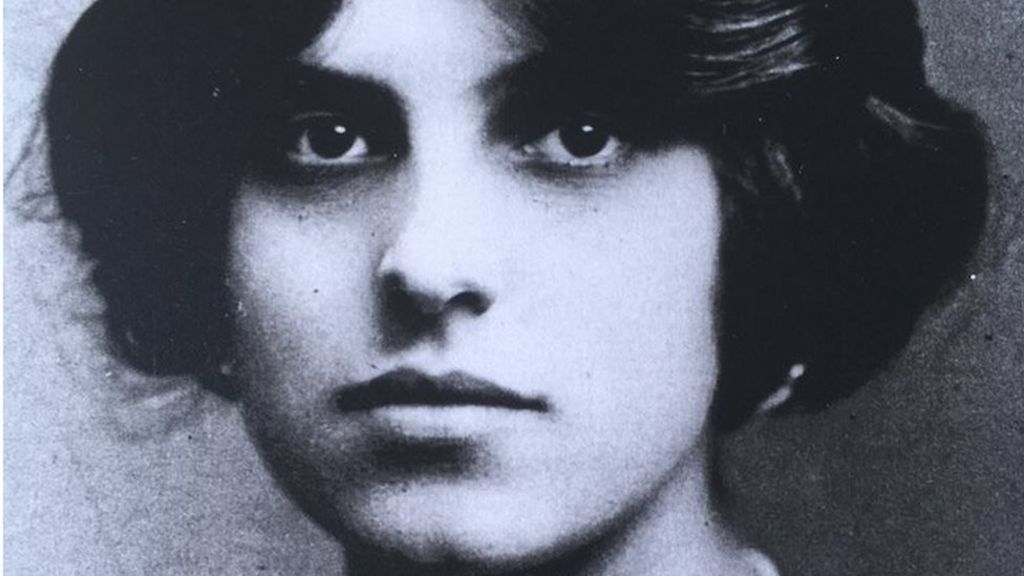

Morfydd Owen's Nocturne in D flat major (1913), at BBC Prom 8 at the Royal Albert Hall, should transform perceptions about Welsh (and British) music history. Thomas Søndergård conducted the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, who premiered its first modern premiere last year, though this performance was far more accomplished. Owen left some 250 surviving scores by the time of her death at the age of 26, of an extensive range including works for large orchestra, chorus, chamber pieces songs and works for stage. To this day, Owen's tally of prizes awarded by the Royal Academy of Music remains unrivalled. Though she was not part of the male English Establishment, Owen needs no special pleading. Her music stands on its own merits, highly individual and original. Her work was published in the Welsh Hymnal when she was 16, before she graduated from Cardiff and moved to London, where she moved in Bohemian, arty circles with the likes of D H Lawrence, Ezra Pound and Prince Yusupov, one of the conspirators who assassinated Rasputin. A "new woman" she was also independent and had a second career as a singer, hence her fluency in writing for voice. Unlike far too many supposedly "lost" composers, Owen's legacy was substantial. Her reputation doesn't rest on sentimentality or gender alone, but on the hard evidence of her music itself.

The Nocturne is sophisticated and highly original, which compares well with much else written at the time. A mysterious woodwind melody calls forth, answered by the strings. The line is is illuminated by tiny bright woodwind fragments, before the main theme is developed into poignant song. Again the strings respond, lit by swathes of brighter winds and harps. Highly atmospheric yet formally structured, this Noctune now eneters a second, more expansive theme which moves with great assurance towards a magnificent crescendo which suddenly shifts to more urbane, lively motifs. If this is a tone poem about night, it's not somnolent but filled with incident and detail. Yet another theme develops, this time led by violin. gradually tension builds up : strong, assertive chords not quite ostinato lead to yet another theme, like a lyrical dance for solo woodwind, garlanded by strings and harps. Such deftness of design, such precise orchestration, and such beauty. All packed into barely half an hour, but unhurried and clear of purpose.

Owen's Nocturne reminded me of Debussy Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune and even possibly of Stravinsky, whose work Owen would have known, given her interest in what was happening in Paris and Russia. Yet its serene confidence is highly distinctive : Owen most definitely had a voice of her own, though she was only 22 when it was completed. BBC NOW should make this Nocturne part of their standard repertoire and explore more of Owen's unique and fascinating music. Please also read my other two articles on Morfydd Owen : Talent has No Gender and Portrait of a Lost Icon. (which is about the groundbreaking recording of her songs. Both include liniks to Tŷ Cerdd, pioneers of Owen's music and of other Welsh composers.

Unfortunaterly the BBC's obsession with artificial themes yet again obscured the music. The tag "Youthful Beginnings" is pretty meaningless in itself, hence the need to include pieces by Lili Boulanger and early Mendelssohn and Schumann, which otherwise don't cohere as a programme. Boulanger and Morfydd Owen were almost exact contemporaries and died young, but that's where the similarities end. Though Boulanger won the composition prize at the Prix de Rome aged 19 - no small achievement - she didn't leave as much as Owen did. Again, perfectly fair enough, everyone develops at different rates. D'un matin de printemps and D'un soir triste are delightful if somewhat slight, but her reputation was bolstered vigorously by her sister Nadia and her followers. These pieces are heard fairly frequently (last November with John Storgårds) because programme planners need to fill agendas about gender. Owen's music speaks for itself regardless of reputation.

Bertrand Chamayou was the soloist in Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto no 1 in G minor, which was balm to listen to. No special pleading needed. Whatever his sex and age, Mendelssohn had a unique musical personality which makes his music distinctive. Søndergård concluded Prom 8 with Schumann's Symphony no 4 in D minor, in the version dating from 1841. This was his glorious Liederjahre when a stream of masterpieces burst forth unstemmed. It's not the work of an immature composer, but rather of one who has so much to say that he needs to get it down quickly. This version instead of the better known 1851 revision has merit. The orchestration is freer and more spontaneous, textures brighter and livelier. Søndergård understood why it matters that the four movements flow one into the other. They're so full of inventive spirit that it would be wrong to hold them back to make them "neat". Great energy, even moments of quirky humour. Low brass and winds blast, almost in parody of stolid ostentation. A vivacious climax, wittily and succintly achieved. This version of Schumann's symphony is hardly unknown but how refreshing and vital it felt in this performance!

No comments:

Post a Comment