|

| Curtain call : Vladimir Jurowski, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Festival Hall |

Mahler as dramatist! Mahler

Symphony no 8 with Vladimir Jurowski and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall. Now we know why Mahler didn't write opera. His music is inherently theatrical, and his dramas lie not in narrative but in internal metaphysics. The Royal Festival Hall itself played a role, literally, since the singers moved round the performance space, making the music feel particularly fluid and dynamic. This was no ordinary concert. What it lacked in interpretive depth was made up for in being well performed, and more than compensated by the imaginative verve of the semi-staging and the way it highlighted structural ideas in this symphony.

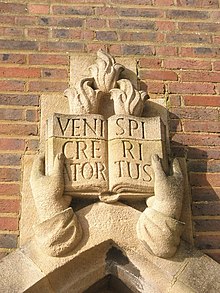

Intriguing questions. Why, for example, preface a two- hour symphony with the ten-minute Thomas Tallis

Spem in alium ? The motet is written for forty parts in eight groups of five voices, mirroring the five voice types of the soloists in the symphony. Tallis's text refers to the "Creator caeli et terrae", while Mahler refers to the hymn "Veni, Creator Spiritus" marking the Pentecost, where a divine flame appeared to the faithful, charging them with spreading the gospels to the world. Six hundred years separate the Maurus hymn from Tallis, but in Mahler, the ancient past is re-created for modern times. Thus a sense of primeval continuity, as if an

Urlicht were descending upon those who perform and listen to the symphony. Hardly had the singing faded when Jurowski led the orchestra straight into the symphony, without pause. From exquisitely balanced unaccompanied harmonies to the explosive chords of the organ. The "Shock of the New" in every way, for Mahler's

Symphony no 8 is unique in so many ways. Thus anointed, we were prepared for Mahler's journey into new territory

This juxtaposition of Tallis and Mahler came perhaps from the concept "Belief and Beyond Belief" the theme of the LPO's year-long series. By no means are all beliefs Christian. While the First Part of the symphony is shaped in the liturgy of the past, the Second Part, despite its references to saints, is secular, based on Goethe's

Faust and on a highly unorthodox blend of lust, sin, death and redemption. Gretchen wasn't a virgin, yet Faust is saved by her intervention.

Das Ewig-wiebliche, the "Eternal Feminine" for Mahler was entirely personal, and very much as odds with conventional morality.

Thus the logic in this case of inserting an interval between the First and Second Parts of the symphony, which otherwise should be sacrilege. The two Parts of the symphony are meant to be played together without a break, since the slow, quiet beginning of the Second Part acts as an important transition, a kind of "Purgatory" between one plane and another. To split the two parts to make way for a drinks interval is musically inappropriate - Mammon polluting the Temple - the prerogative of philistines. But in this performance, the interval made sense, because it emphasized that the difference between the two parts represents a shift in metaphysics more profound than musical logic. Context is everything, and hopefully audiences will be sophisticated enough to realize that this exception should not become the rule.

The name "Symphony of a Thousand" was not Mahler's idea, but a slogan created by the promoter of the premiere, who realized how the blockbuster aspects of the symphony could be marketed. Because of its sheer theatrical impact, this massive symphony will always be stunning. But as Mahler so explicitly states, the vast forces are bearers of "poetic thoughts", so powerful that they need ambitious expression. It's not spectacle for the sake of spectacle, not a circus for pulling stunts of sheer people management. While volume may be exciting, quantity most certainly is not more important than quality. Both times that I've heard

Mahler's Eighth in the Royal Albert Hall, the results weren't convincing since the sound dissipated badly under the cavernous dome.

The Royal Festival Hall seats 2900, so a thousand players would be deafening. Fortunately, Jurowski got around the problem by spreading the singers around the performance space, instead of concentrated in one focal point, deafening audience and orchestra. Sometimes the choirs ranged around the side galleries, where they were heard clearly and to full effect. Wonderful hushed singing, barely above whisper: in a symphony as big as this, that's something special. When the choirs were positioned behind the orchestra, they operated as individual units for the most part until the glorious finale. What a pleasure it was to hear each group distinctly, as opposed to hearing them blended en masse. Much respect for them, singing so well and so clearly, despite rushing about. Incidentally, positioning the choirs in the side galleries resembled the "horseshoe" formation adopted in some early music ensembles The soloists at first appeared in a line between orchestra and choirs. the "sweet spot" in the Royal Festival Hall acoustic. This lessened the strain : no-one forced to shout to be heard.

In the Second Part, the soloists moved positions much more than they do normally. One expects the Mater Gloriosa to sing from on high like an angel, but the other singers moved around, too, especially the women, and Matthew Rose remained surrounded by the orchestra, his deep bass carrying well over the sounds around him. Choirs in motion, singers in motion, but not nearly as distracting as one might fear. The Second Part of this Symphony was inspired by art to which modern perspective did not apply. Thus figures float about disconnected to the landscapes behind them, as oddly as lions behaving like lambs. Similarly, Goethe's

Faust depicts unnatural movement - flying through skies, ascension into heaven and so forth. The textures in Mahler's orchestration suggest multiple levels and layers and interesting combinations of instruments and voice. The symphony is constantly in motion.

Throughout Mahler's

Symphony no 8, images of light and illumination recur. In this performance, lighting effects (Chahine Yavroyan) were used to emphasize contrasts. Small lights, flickering above the music stands, helping the players follow the page while the hall was in darkness. Large spotlights , highlighting groups of choristers as they sang. The Royal Festival Hall organ, usually hidden behind a screen, was fully open, lit in rich shades of sapphire, alternating gold, and towards the end, silver and iridescence. The organist was James Sherlock.

The presence of microphones in the hall suggested that a recording or broadcast may be available at some stage. All live performances have something extra: this Jurowski/LPO Mahler Symphony no 8 was unique, an experience never to forget.

Soloists were : Judith Howarth, Anne Schwanewilms, Sofia Fomina, Michaela Selinger, Patricia Bardon, Barry Banks, Stephen Gadd and Matthew Rose. Choirs were the London Philharmonic Choir, the London Symphony Chorus, the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge and the Tiffin Boys' Choir.

This review also appears in Opera Today

Please see my 11 other posts on

Mahler Symphony no 8 by clicking on the label below

.jpg)