Chairman Mao (Mao Tsetung) meets Richard Nixon, President of the US in 1972. It's the subject of John Adams's opera Nixon in China which has come at last to the Met in NY after 23 years. Having lived through those times from a different perspective I was worried the opera might be crass, but no problems. John Adams and Peter Sellars (who directed the HD film) are to real history and to China as Sarah Palin is to geopolitics because you can see Russia from Alaska.

Sellars tells Thomas Hampson in one of the intervals that 22/2/72 was as important to world history as 9/11. No. It's not a cosmic struggle between east and west. Nixon needed to end the Vietnam war and Taiwan was a historic millstone. China didn't have much to gain or lose either way (though it bugged the Russians). But Nixon in China works as a study of political gullibility. Both sides are manipulating the media to fool each other. It's a game of tactics. A sharp diplomat reads the codes. Notice the white vase on the floor by Mao? Why do Nixon (James Maddalena) and even Chou Enlai (Russell Braun) look appalled? The white vase is a spittoon, which Mao uses frequerntly. Old men used such things then, but it's also symbolic of what Mao thinks of the world.

Sellars tells Thomas Hampson in one of the intervals that 22/2/72 was as important to world history as 9/11. No. It's not a cosmic struggle between east and west. Nixon needed to end the Vietnam war and Taiwan was a historic millstone. China didn't have much to gain or lose either way (though it bugged the Russians). But Nixon in China works as a study of political gullibility. Both sides are manipulating the media to fool each other. It's a game of tactics. A sharp diplomat reads the codes. Notice the white vase on the floor by Mao? Why do Nixon (James Maddalena) and even Chou Enlai (Russell Braun) look appalled? The white vase is a spittoon, which Mao uses frequerntly. Old men used such things then, but it's also symbolic of what Mao thinks of the world.

This production is based on historic photos of real events so the designs (Adrianne Lobel) are eerily unsettling. Costumes (Dunya Ramikova) are so accurate they must have been custom dyed. Mao looks uncannily healthy, but we know he often used body doubles not just because he was a sick man but because he was a creep. The big banquet is there and the Potemkin schoolchildren are there, though the moment where Chou feeds Nixon with chopsticks is underplayed in the opera. Feeding guests prize titbits is basic good manners in China, but Chou was also making a political point. What might be tasty to Chou just might be something Nixon won't eat.

Adams's music drones like the hum of a giant machine, which is appropriate enough for a society reduced to automatons, but would benefit from being edited judiciously. What really saves the opera is the word setting. The libretto (Alice Goodman) is brilliant. She uses stock phrases like "Manifest Destiny" in quirky ways. Usually the term is US expansion to the west. Here, it's China in Vietnam. Similarly sound bite phrases are dissected and re-arranged so they sound like gibberish. Which is exactly how the media uses what really happens. Nixon's speech on arrival is brilliantly well written in this way. The libretto makes the opera, bringing depths that the charcaterizations altogether lack. Sellars's statement, that the libretto is poetic in the way that Yeats, Eliot and the Chinese masters are, is utter nonsense, though.

Maddalena's Nixon knows he's out of his depth when he talks sense, but Mao doesn't care. He's obviously done his homework since he refers to Wang Ming and other political heavies whom Mao carefully excludes. If only politicians still did briefings based on proper risk assessment. Blair told the world he was right to invade Iraq because he asked God, and God said nothing. Nixon would be weeping that things have come to this. Watergate was small cheese compared to what happens now. Nixon comes over as well meaning, and a decent man who's too polite to question the gibberish Mao spouts. Philosophy? Trolls also speak in riddles. Maddalena created the role in 1987 so deserves much respect. If his voice is aging, so be it, for this is one of the keynotes of his career and deserves being commemorated on film.

Robert Brubaker as Mao Tsetung is excellent. Despite his crisp new suit Brubaker exudes sleaze. I don't know if the scene where he gropes one of his aides was in the original production, but it's necessary now from what we know of Mao's private life. Russell Braun's Chou Enlai was as stiff as a corpse. Admittedly the man himself was unwell but it was nearly 4 years before he died, struggling to the end. He, too, isn't quite as innocent as portrayed. Neither was Henry Kissinger (Richard Paul Fink) a buffoon who can't even find a toilet.

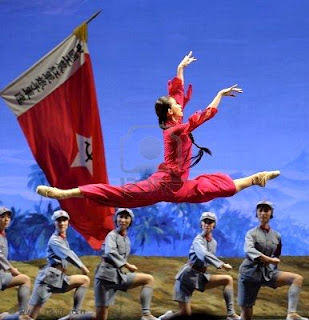

So what's behind the flights of fancy ? What is Adams trying to say and what point is he trying to make? Surely not something as banal as "in bed we dream"? Pat Nixon (Janis Kelly) comes over as unbelievably naive, though she can't have been since she was a pillar for her husband, even if it came at a price. Pat and Tricky Dick werer tough political animals, so why does Pat lose it when she sees something that's obvioulsy not fake? The ballet being shown is The Red Detachment of Women, (click link for full download), also faithfully depicted in accurate detail (kapok trees, palms) It's full blown propaganda, mixing ballet, didactics and the stylization of Chinese opera.

If only Adams, Sellars and Goodman had thought through these ideas instead of merrily making things up. They hint that all's not well when Pat pops pills, but that's not enough. Nixon's reminiscences about The Pacific are pointlessly irrelevant. Hainan is not Guadacanal, and even if it was, the issues are completely different.

The formidable Chiang Ching is so well realized by Kathleen Kim that she stole the show. She was an outstanding Olympia in the recent Met Les Contes d'Hoffmann. Wonderful, searing high notes, meant to grate on the nerves. She's the one who ran the Cultural Revolution while Mao was senile. Chou nearly lost his job. So why is she turned into a sex siren? Of course we know she was an actress when she met Mao but he went through wives and mistresses like other men change shoes. Maybe it helps sell the opera to western audience to add an exotic in silk qipao, but it's pretty hard to make connections. Kim is so good that perhaps the Met will cast her in serious mainstream roles.(the photo shows Chiang Ching shouting back at the prosecutors when she was on trial for her life in 1981. She got away with a life sentence but damaged all the dolls she was forced to make as a prisoner so that they couldn't be sold)

The formidable Chiang Ching is so well realized by Kathleen Kim that she stole the show. She was an outstanding Olympia in the recent Met Les Contes d'Hoffmann. Wonderful, searing high notes, meant to grate on the nerves. She's the one who ran the Cultural Revolution while Mao was senile. Chou nearly lost his job. So why is she turned into a sex siren? Of course we know she was an actress when she met Mao but he went through wives and mistresses like other men change shoes. Maybe it helps sell the opera to western audience to add an exotic in silk qipao, but it's pretty hard to make connections. Kim is so good that perhaps the Met will cast her in serious mainstream roles.(the photo shows Chiang Ching shouting back at the prosecutors when she was on trial for her life in 1981. She got away with a life sentence but damaged all the dolls she was forced to make as a prisoner so that they couldn't be sold)

The dancers were very good - dancing en pointe to machine gun fire isn't easy. Mark Morris was the choreographer but the ballerina in red doesn't seem to get credit. Adams Nixon in China wasn't as bad as I thought, but could use judicious editing and much more thoughtful direction, especially in the last fantasy act. Even if the opera deals with media manipulation, it falls apart if it gives up half way. Maybe Nixon should have dumped Pat for Chiang Ching (he might still be in power) but this self-indulgent production runs out of steam just as it's getting somewhere. (Please see my posts on Dr Atomic, A Flowering Tree and many others on China) Photo credit : Ken Howard, Metropolitan Opera

Sellars tells Thomas Hampson in one of the intervals that 22/2/72 was as important to world history as 9/11. No. It's not a cosmic struggle between east and west. Nixon needed to end the Vietnam war and Taiwan was a historic millstone. China didn't have much to gain or lose either way (though it bugged the Russians). But Nixon in China works as a study of political gullibility. Both sides are manipulating the media to fool each other. It's a game of tactics. A sharp diplomat reads the codes. Notice the white vase on the floor by Mao? Why do Nixon (James Maddalena) and even Chou Enlai (Russell Braun) look appalled? The white vase is a spittoon, which Mao uses frequerntly. Old men used such things then, but it's also symbolic of what Mao thinks of the world.

Sellars tells Thomas Hampson in one of the intervals that 22/2/72 was as important to world history as 9/11. No. It's not a cosmic struggle between east and west. Nixon needed to end the Vietnam war and Taiwan was a historic millstone. China didn't have much to gain or lose either way (though it bugged the Russians). But Nixon in China works as a study of political gullibility. Both sides are manipulating the media to fool each other. It's a game of tactics. A sharp diplomat reads the codes. Notice the white vase on the floor by Mao? Why do Nixon (James Maddalena) and even Chou Enlai (Russell Braun) look appalled? The white vase is a spittoon, which Mao uses frequerntly. Old men used such things then, but it's also symbolic of what Mao thinks of the world.This production is based on historic photos of real events so the designs (Adrianne Lobel) are eerily unsettling. Costumes (Dunya Ramikova) are so accurate they must have been custom dyed. Mao looks uncannily healthy, but we know he often used body doubles not just because he was a sick man but because he was a creep. The big banquet is there and the Potemkin schoolchildren are there, though the moment where Chou feeds Nixon with chopsticks is underplayed in the opera. Feeding guests prize titbits is basic good manners in China, but Chou was also making a political point. What might be tasty to Chou just might be something Nixon won't eat.

Adams's music drones like the hum of a giant machine, which is appropriate enough for a society reduced to automatons, but would benefit from being edited judiciously. What really saves the opera is the word setting. The libretto (Alice Goodman) is brilliant. She uses stock phrases like "Manifest Destiny" in quirky ways. Usually the term is US expansion to the west. Here, it's China in Vietnam. Similarly sound bite phrases are dissected and re-arranged so they sound like gibberish. Which is exactly how the media uses what really happens. Nixon's speech on arrival is brilliantly well written in this way. The libretto makes the opera, bringing depths that the charcaterizations altogether lack. Sellars's statement, that the libretto is poetic in the way that Yeats, Eliot and the Chinese masters are, is utter nonsense, though.

Maddalena's Nixon knows he's out of his depth when he talks sense, but Mao doesn't care. He's obviously done his homework since he refers to Wang Ming and other political heavies whom Mao carefully excludes. If only politicians still did briefings based on proper risk assessment. Blair told the world he was right to invade Iraq because he asked God, and God said nothing. Nixon would be weeping that things have come to this. Watergate was small cheese compared to what happens now. Nixon comes over as well meaning, and a decent man who's too polite to question the gibberish Mao spouts. Philosophy? Trolls also speak in riddles. Maddalena created the role in 1987 so deserves much respect. If his voice is aging, so be it, for this is one of the keynotes of his career and deserves being commemorated on film.

Robert Brubaker as Mao Tsetung is excellent. Despite his crisp new suit Brubaker exudes sleaze. I don't know if the scene where he gropes one of his aides was in the original production, but it's necessary now from what we know of Mao's private life. Russell Braun's Chou Enlai was as stiff as a corpse. Admittedly the man himself was unwell but it was nearly 4 years before he died, struggling to the end. He, too, isn't quite as innocent as portrayed. Neither was Henry Kissinger (Richard Paul Fink) a buffoon who can't even find a toilet.

So what's behind the flights of fancy ? What is Adams trying to say and what point is he trying to make? Surely not something as banal as "in bed we dream"? Pat Nixon (Janis Kelly) comes over as unbelievably naive, though she can't have been since she was a pillar for her husband, even if it came at a price. Pat and Tricky Dick werer tough political animals, so why does Pat lose it when she sees something that's obvioulsy not fake? The ballet being shown is The Red Detachment of Women, (click link for full download), also faithfully depicted in accurate detail (kapok trees, palms) It's full blown propaganda, mixing ballet, didactics and the stylization of Chinese opera.

If only Adams, Sellars and Goodman had thought through these ideas instead of merrily making things up. They hint that all's not well when Pat pops pills, but that's not enough. Nixon's reminiscences about The Pacific are pointlessly irrelevant. Hainan is not Guadacanal, and even if it was, the issues are completely different.

The formidable Chiang Ching is so well realized by Kathleen Kim that she stole the show. She was an outstanding Olympia in the recent Met Les Contes d'Hoffmann. Wonderful, searing high notes, meant to grate on the nerves. She's the one who ran the Cultural Revolution while Mao was senile. Chou nearly lost his job. So why is she turned into a sex siren? Of course we know she was an actress when she met Mao but he went through wives and mistresses like other men change shoes. Maybe it helps sell the opera to western audience to add an exotic in silk qipao, but it's pretty hard to make connections. Kim is so good that perhaps the Met will cast her in serious mainstream roles.(the photo shows Chiang Ching shouting back at the prosecutors when she was on trial for her life in 1981. She got away with a life sentence but damaged all the dolls she was forced to make as a prisoner so that they couldn't be sold)

The formidable Chiang Ching is so well realized by Kathleen Kim that she stole the show. She was an outstanding Olympia in the recent Met Les Contes d'Hoffmann. Wonderful, searing high notes, meant to grate on the nerves. She's the one who ran the Cultural Revolution while Mao was senile. Chou nearly lost his job. So why is she turned into a sex siren? Of course we know she was an actress when she met Mao but he went through wives and mistresses like other men change shoes. Maybe it helps sell the opera to western audience to add an exotic in silk qipao, but it's pretty hard to make connections. Kim is so good that perhaps the Met will cast her in serious mainstream roles.(the photo shows Chiang Ching shouting back at the prosecutors when she was on trial for her life in 1981. She got away with a life sentence but damaged all the dolls she was forced to make as a prisoner so that they couldn't be sold)The dancers were very good - dancing en pointe to machine gun fire isn't easy. Mark Morris was the choreographer but the ballerina in red doesn't seem to get credit. Adams Nixon in China wasn't as bad as I thought, but could use judicious editing and much more thoughtful direction, especially in the last fantasy act. Even if the opera deals with media manipulation, it falls apart if it gives up half way. Maybe Nixon should have dumped Pat for Chiang Ching (he might still be in power) but this self-indulgent production runs out of steam just as it's getting somewhere. (Please see my posts on Dr Atomic, A Flowering Tree and many others on China) Photo credit : Ken Howard, Metropolitan Opera

1 comment:

You know what your problem is? You thought you were going to watch a documentary. "Stylized" is obviously a word that doesn't mean much to you, much less the phrase "stylized representation of events".

Post a Comment